by Kelsey Leach

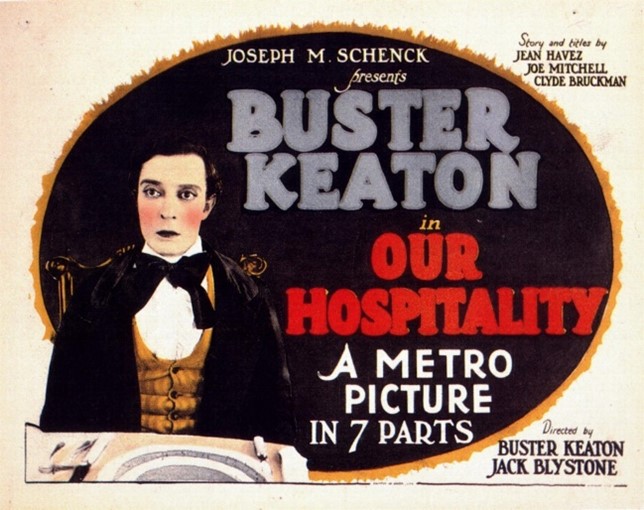

On Sunday the 24th, I attended the first event of the week-long 1st Annual Pittsburgh Silent Film Festival: a screening of Buster Keaton’s Our Hospitality (1923) with live Wurlitzer theater organ accompaniment by Jay Spencer, the House Organist from the Palace Theatre in Canton, OH. It was an afternoon of pure delight, a spectacle of wildly talented artists from two different centuries reveling in a sense of freedom, levity, and infectious joie de vivre that is sometimes hard to come by in adult life.

My friends and I filed into the unassuming school auditorium; the majority of the crowd had about forty years on us. We’d bought the tickets on a whim and didn’t know what to expect.

The organ beckoned from a corner of the stage; its presence loudly ornate. Gold flourishes and candy-colored keys shone with unique mystery, the sudden pure and childlike curiosity I felt when I walked in nearly as rare as the Wurlitzer itself.

It was time for the show to begin. The lights went out all at once, then flashed on again, as if someone had made a mistake. The audience murmured surprise. The drama felt appropriate.

A single spotlight lit the stage, conjuring a vaudevillian aesthetic. During the introduction by the Pittsburgh Silent Film Society, we learned that Our Hospitality is the only film that features three generations of the Keaton family: Buster’s father, Joe, appears as the locomotive engineer, and his infant son, Buster Keaton, Jr., appears as a young version of Buster Keaton’s character, Willie McKay. His wife at the time, Natalie Talmadge, was also cast in the film. It’s a kind of loosely arranged family portrait, a snapshot of the Keaton family in that moment.

Our Hospitality is likely part of a collection of films saved from ruin by British actor James Mason. He discovered a collection of Buster Keaton’s work in the actor’s former home when he purchased it in 1948. Film studios had been in the habit of “recycling” old film to reclaim the silver and countless silent movies had already been lost. In other words, we were lucky.

Organist Jay Spencer took the stage. He began talking about trains, and a certain train that was about to appear in the film in particular; little did we know, we were embarking on a transportive journey of our own with Spencer as conductor. His black jacket was possibly silk, possibly velvet; his two-tone black and white dress shoes seemed to belong to the bygone era of the silver screen. The journey was about to become a little bit magical, and, like Keaton with his wry, hilariously self-aware performance, Spencer knew it before we did and he relished every minute. His eyes twinkled behind his glasses. My eyes welled up when he began to play.

The experience of watching a film with a person who is both a spectator and a part of the film itself is a truly immersive experience. We were watching a movie with the movie. Spencer’s prancing hands, his pumping heel, his body lilting with the music–all of it was an extension of Keaton’s visceral antics on screen. The music and the movement of the musician danced alongside the silent performance with an exactness and alacrity you would have to see to believe. Spencer created a portal through time, which, as we struggle to escape the shadow of the pandemic’s resulting temporal and spatial isolation, felt revolutionary. Rarely do we feel physically close to the distant past, but there on the screen was a film from the last century, and there on the stage was a live person playing the score.

Keaton mounted a horse and the organ trotted along; Keaton swayed precariously from the end of a rope over a cliff and the organ balanced on a precipice of high notes. Keaton, utterly skilled in the art of restraint and exaggeration, seemed to know precisely when to do very little and when to do it all. He tried to don a tall hat in a low-ceilinged train car; it didn’t fit; we laughed. He was caught stroking his beloved’s hand by the lady’s father and played it off in such a spastic series of casual stances that he only managed to incriminate himself more. He was jaunty, sharp, wily, charismatic, unhinged, cocky. There was violence, romance, adventure, danger, and tenderness. There was a dog. This film from 1923 seemed to span more genres and use more filmmaking techniques than a large majority of modern day blockbusters with exponentially more money and technology available. Isn’t this fun? Keaton’s actions seemed to say, and Spencer’s swaying body agreed. In fact, Spencer’s playing was so precise that ten minutes into the film I had completely forgotten he was there at all. Later, my eyes wandered down to the organ again: Oh my god, I thought, he’s been playing this whole time.

When the movie was over, Spencer bowed and retreated quickly from the spotlight to stand in the shadow of the organ. We clapped and clapped, applauding him, applauding it. Again, with purposeful drama, he stepped into the spotlight and asked if we wanted one more. We clapped and whistled and immediately fell silent. We waited with breathless, palpable impatience, and when it was over, met him with a standing ovation.

Afterward, a friend pointed out the irony. How in 2023, we’re enamored with something as lo-fi as a silent film accompanied by live organ music, yet when the first talkie came out in 1927, the ability to synchronize sound and motion picture was the spectacle of the moment. Novelty is relative, it seems–like time itself.

We spilled out of the school and waded through the damp, chilly grass like jaded protagonists from an 80s teen drama. My friends and I went for burgers at a nearby place that was a modern take on a classic diner: teal and milkshakes and shoestring fries. I was wearing a vintage plaid duster jacket I had picked up at an estate sale the day before. Everything was glamorous and nostalgic and strangely anachronistic–in a word, magical. I hadn’t experienced anything like it in a long time.

Kelsey Leach is a Pittsburgh-based writer and creative director. More information about the Pittsburgh Silent Film Society can be found on their website.

Leave a comment