by Richard Engel

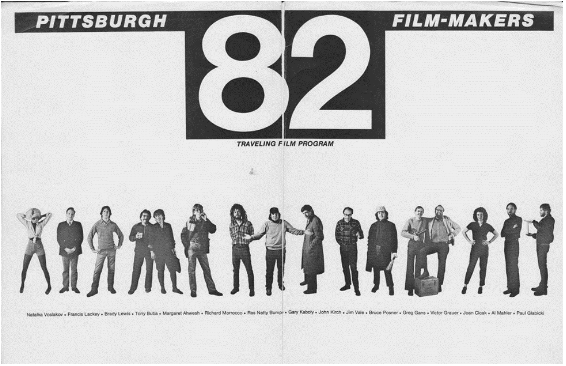

Cover image–Natalka Voslakov, Peggy Ahwesh, Tony Buba, “Morrocco” and other artists whose work was in PFMI’s 1982 traveling program

Pittsburgh Sound + Image, led by Steven Haines and Steve Felix, has been doing some of the work we used to see from the now-defunct Pittsburgh Filmmakers (PFMI). They don’t run a big annual festival, or show the latest two-hour art titles, but instead they research and try to rescue local film and video, as well as exhibiting monthly at the Eberle ceramics studios in Homestead, PA. Their recent show of local video pro Henry Roll’s joyful experiments was a relief during the August heat here. On September 29, as the fifth in a six-part “Essential Pittsburgh” screening series done with support from the Steel Valley Enterprise Zone, they presented a full program by or about local actress, poet, and Super-8 artist Natalka Voslakov.

While her better-known contemporaries Tony Buba and Peggy Ahwesh were creating dry humor, documenting out-of-style milltown characters, or filming verité hangs with androgynous slackers, Voslakov was making more self-exploratory or self-referential work, fleshing out her own monologues into poignant riffs on misogyny, on leaving your town and your family, and trying to understand men.

Tammy Wynette’s “Stand By Your Man” is a very-well-worn signifier now and might already have been in 1979 when Voslakov made “Grade B Delivery Boys,” a relaxed and repetitive handpainted piece. Trigger warning: smoking! A pair of nude women in toy shades converse on a sofa. The sepia-toned scene is joined by a devoluted pizza delivery guy, who’s kissed and tipped in cash. After a playful unrolling of tape, our heroines nibble slices and wrap up three men in good cheer.

Natalka didn’t just make her own films. She was in many, including Peggy Ahwesh’s “Philosophy in the Bedroom, Part I” (1987) and in Tony Buba’s now-renowned “Lightning Over Braddock” (1988). She worked on many of the PFMI member newsletters in the late ’70s.

“The great love of her life was cut short by a motorcycle accident, and her reaction to this was to recreate herself,” Bill Boichel told me. Bill was the exhibitions director at PFMI from 1982-84 when Natalka was still active; his Copacetic Comics is a valuable hub in Pittsburgh’s Polish Hill. “Her new character was like both a Warholian observer and a Factory superstar. …She made art because she had to, to survive. Like so many of her friends in punk music, she simply picked up the tools and started.”

“Project for the Haunting of a House” (1978) juxtaposes traditional-sounding Asian instrumentation and refracted building and tree forms. This was described in the discussion after the screening as “the house above the Winky’s” in Swissvale by two of Natalka’s children, Zoe and Zoltan.

In “Modeling Film 8-15-77” (1977) we briefly glimpse a Black male model arrive and strip, then multiple white photographers including Robert Haller jaggedly shoot from above at length.

Ben Ogrodnik studied the region’s part of the “Super-8 Chic” scene as part of his recent film Ph.D study at University of Pittsburgh. Ben told me: “there are great stories about Natalka in (her and Peggy’s close friend and collaborator) Margie Strosser’s diaries. To quote Margie, Natalka was the actress and comedienne, the writer, the poet, the social maven and the make-up artist. Peggy was avant-garde, Natalka was popular culture.”

Natalka met Peggy on a George Romero project, Creepshow, where the two became best friends and collaborators. As Ahwesh has described it, “I had a very flamboyant best friend, Natalka Voslakov. She’s in some of my movies, and I shot some of her movies. She was one of the staples of my Pittsburgh years, an incredibly striking woman. Of course, she got a much better job with Romero than I did [laughter]—she was first assistant to the assistant director. My friend, Margie Strosser, who I’ve worked with over the years, was an assistant editor. We all got to know each other.” (Millenium Film Journal, 2003)

Many of the actors in the screened films were also musicians and filmmakers from the small Pittsburgh punk scene of the time. Rich Moore makes a delivery in goggles in one; he sat on the Pittsburgh Filmmakers board in the early ’80s and made his own films as “Rick Morrocco.” Sometimes he would babysit Natalka’s kids. He attended the show Friday.

“Natalka was just a wild woman,” Moore told me. “She always had a million ideas, she was driven to make an art career. …But to get validation for your work it has to get seen and that takes ‘who you know’ but also—it took money back then, to make prints, or to blow up to 16 millimeter for any real distribution. The [PFMI] traveling show helped. Bill Judson [at the Carnegie Museum of Art’s film section] could help some people get state arts grants. …We would put on our own screenings, of course. Having our friends who were local musicians in the films would bring a few more people out to watch, you know.”

Moore worked at Western Psychiatric hospital and later in corporate video and studio tech; other Pittsburgh film artist/actors like Buba and Ahwesh and Brady Lewis taught at the college level. But Natalka led a more working-class life, stayed in the Mon Valley and raised her kids. “We were broke,” Zoltan told the crowd afterwards.

We had some fun seeing her kids in “Zoom-Zoom Dance” and “When the Whip Comes Down” (1979). We watched a poet friend read and dispute an article in the paper about Natalka. Later her kids are older, playing basketball outside. Vintage film clips and “The Young & The Restless” are spliced in; doo-wop tunes blare in and out.

“Who Is Natalka Voslakov?” a 1988 portrait by Zed Armstrong (also in attendance Friday), shows Natalka glamorously dressed and talking about her youthful artistic ambitions. Her frank need for men and lack of understanding of them plays pointedly against butch fashion and women’s “machisma.”

Later, against a background of kitchen trash she tells us directly, “I like to keep my life and my work separate. Life is where the pain is.” Her “Time Capsule with True Bird Flight” (1982) has a somber, everyday prettiness. The bird is mechanical.

Throughout the screening, in lighter parts of the films, Natalka’s friends and contemporaries in the back rows called out when they appeared on screen. After the screening these friends warmly remembered the artist, through the haze of years and of drink and drugs.

In “Therapy – California in Five Fears” (c.1984) Voslakov brings us high and low, collaging sound from a battered-women hotline, a shoot-em-up soundtrack, surf rock, and haunting Judy Garland over visuals purpose-shot for the project. We’re moved—from a Pittsburgh transit station (down), to a dark sidewalk outside a club (over), the Duquesne incline (up), and a shoreline dance party by an old mill (out, to Cali). Simple captions punctuate, and play off the scene; “LAND OF OZ” it says beneath a low-rent starlet, her fancy shoes on the trashy beach while she’s photoshot from the waist up. Her own narration breaks easily through the busy film: “This town could be any town.”

In the ’80s, Ahwesh, by then beginning what became lengthy career in art film and on the faculty at Bard College, helped get Natalka’s films to NYC where they were presented in a group shows including at MoMA in Big as Life (February 1998—December 1999). In the meantime, she and her kids still rode around in the graffitied car from “Therapy.” “The Zenmobile,” Zoltan called it.

“Peggy tried to be the Bowie to her Iggy,” Boichel said, “and keep her going when she needed help. The same happened with Reid Paley [of local punkers The Five, who appears in some of Natalka’s films] in Boston with Black Francis [of Pixies].”

In her later years, many people told me, Natalka would leave manic voice messages, sometimes paranoid, on answering machines until the tape ran out. While these gluts were inconvenient for her friends that were gig workers reliant on their answering machines to get jobs, and unappreciated by some of the more fastidious artists she’d call, the messages left for Ahwesh found their way into fresh collaborative pieces.

After the show Friday, Zoe called out thanks to the crowd including local film history mavens Michael Prosser and Harrison Apple for working with her and her brother on their home archive, and helping her start making her own, new video work. Gary Kaboly, who appeared in Natalka’s Monongahela “beach” scene in his trademark backwards ballcap (and was in the ’82 traveling show, and ran the PFMI exhibitions department for decades) expressed some surprise afterwards: “Even being there at the time, I’d mostly only seen Natalka’s ‘mumblecore’ style pieces. Seeing some of the more set-up pieces, it just shows the richness of her whole body of work.”

Steve Haines announced at the show that Pittsburgh Sound + Image just received some new funding to preserve “Therapy.” His “white whale” of all local films, he said, is the full-length version of Voslakov’s “Teenage Love,” of which only 20 minutes is currently known; a short excerpt was part of the show Friday. As in their prior Essential Pittsburgh screenings, Pittsburgh Sound + Image produced a detailed, zine-like 12-page program for the event.

Natalka died in 2011, at 59. Her contemporary Harriet Stein wrote then: “For better or worse, Natalka helped get me hooked on art, films, and poetry. Natalka was not only an artist, she was art.”

Richard Engel was the marketing director for Pittsburgh Filmmakers from 2003-2010. He resides in Troy Hill, and urges you to vote this November.

Leave a comment