by David Rullo

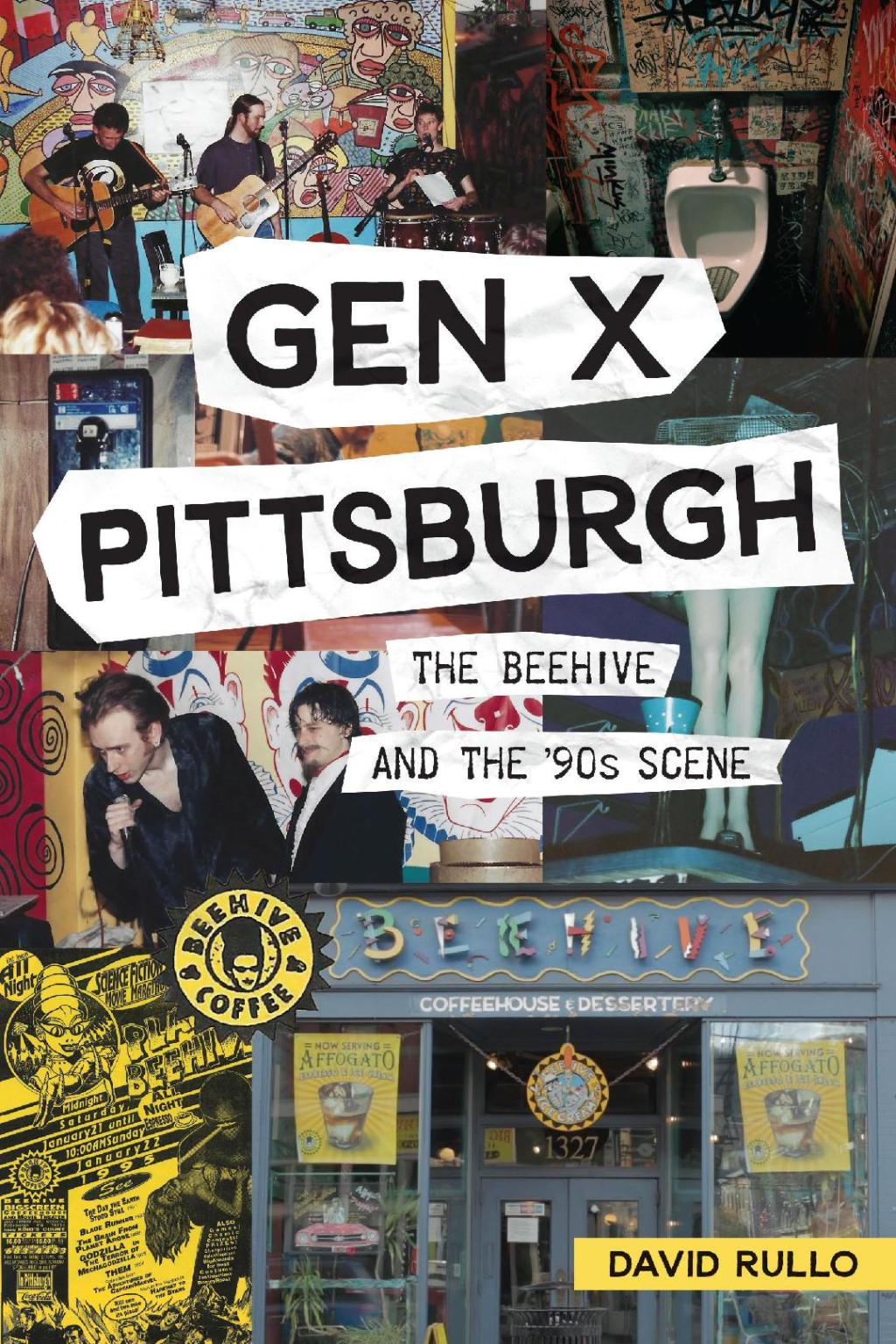

Pittsburgh writer David Rullo will celebrate the publication of his book, “Gen X Pittsburgh: The Beehive and the 90s Scene,” with a publication launch party Nov. 1 at the Tiki Lounge, 2003 East Carson St. “Gen X Pittsburgh: The Beehive and the 90s Scene” takes a deep dive into the history of the Beehive, Pittsburgh’s first coffeehouse, opened in 1991 and the customers, artists, musicians, students and community denizens that made the café such cultural touchstones.

Along the way, it notes the transformation of both the Pittsburgh South Side and Oakland neighborhoods, as they shook themselves free from the post-industrial morass they had suffered since the collapse of Pittsburgh’s steel industry. Rullo notes the change that took place as artists began to rent empty apartments, shot-and-beer bars catering to mill workers began to become hip dive bars and entrepreneurs found inexpensive real estate to follow their visions. The Beehive attracted this now generation, appealing to an alternative 90s crowd that would soon help shape the national conversation and cultural identity. The below is an excerpt from the book. (Editor’s Note: I’ll be at the party – proud South Sider and so excited about this book’s release and the way it highlights how this neighborhood has some of the city’s richest cultural history. See you there! – ER)

“The Beehive changed my life.”

I heard that refrain over and over while writing this book. Artists, photographers, mothers, musicians, circus performers and neighborhood denizens all said the same thing.

I believed them because the Beehive changed my life.

In 1990, I was a freshman at Point Park College, located on the Boulevard of the Allies in downtown Pittsburgh. The city hadn’t yet recovered from the collapse of the steel industry, and the blocks around the school were vacant. A Rax Roast Beef, McDonalds and Subway were all that was available if one wanted a quick meal. There were few art galleries and only a Walden Book Store several blocks away. There was no nightlife or cultural district of which to speak. Even Starbucks was several years away from reaching the city.

Point Park College, not yet a university, was an extremely liberal place of higher learning, bordering on an art school. It was known for its journalism, dance and acting majors and not much more. Its three buildings housed most of its students, as well as artists in training from the nearby Art Institute of Pittsburgh and Pittsburgh Filmmakers. I was studying to be a writer; my friends were musicians and filmmakers. I dated an artist. We hung out with photographers, ballet dancers, future directors and radio personalities in wait. Outside of the school, however, there was little to do during our off-hours. It would be charitable to call the underground art and literature scene downtown and in the nearby South Side and North Side neighborhoods burgeoning.

That was soon to change.

In 1991, the ’90s hadn’t yet started. The calendar might have alleged it to be the ninth decade of the twentieth century, but that was purely coincidental.

When the Beehive opened its doors, six months after I started my freshman year, Pittsburgh was still best known for its failing steel mills, polluted air, once dominant football team and colloquial accent. Generation X and the youth transformation that came with it wasn’t yet part of the cultural zeitgeist. And yet, a funny thing happened on the way to the stadium; the coffeehouse found a loyal and large customer base with virtually no advertising or promotion. Kids with green hair, tattoos, ripped jeans and pierced noses started showing up in a neighborhood not yet known as ground zero in the city’s art scene.

The Beehive became, if you’ll excuse the pun, a hive of social activity before the advent of social media. Artists began calling the café home, musicians spent time there between gigs and college students started and ended their nights at the coffeehouse. An ethos formed both inside and outside the walls of the espresso bar.

To those who weren’t part of the scene, the clientele was something new for Pittsburgh’s South Side neighborhood. They didn’t fit in with the shot-and-beer mentality built around the neighborhood. They took parking spaces, were loud, were considered ignorant, didn’t wear Steelers or Pirates caps and certainly didn’t look like the good kids the neighborhood had raised who attended city or Catholic schools.

That was only one side of the story though.

For those in the know and for that first generation of Beehives customers, the coffeehouse was a place where they could find others like themselves. Outside, they might have been considered freaks and losers, but inside, they found fraternity and sorority. They could talk about music and art. They didn’t seem pretentious or weird. They found their tribe.

A simmering tension existed between the neighborhood and the caffeine-based establishment until those living near the café began to slowly, begrudgingly accept that their once cloistered neighborhood was becoming the artsy hangout for a group of Pittsburghers. Their once deserted storefronts would begin to be populated by businesses with a similar vibe—Slackers, Groovy, the Culture Shop, the Lava Lounge—even formerly safe environs like Dee’s Café would shake off the last vestiges of its industrial past and welcome a new generation.

I wasn’t aware of the social impact of the Beehive when I found it. I simply knew I discovered a place where I fit in.

I had grown up mostly in Western Pennsylvania suburbs, with a brief New England stopover. My parents and the parents of my friends were either the first generation not working in a mine, steel mill or industrial plant or had recently become unemployed from a mine, steel mill or industrial plant and were still figuring out what that meant.

I wasn’t supposed to aspire to be a writer. I certainly wasn’t supposed to have my hair fashioned in a skater’s cut, wear a three-quarter-length leather coat that I picked up in a thrift shop, spend my time visiting bookstores and record stores trying to find out-of-print editions of Jack Kerouac novels or Charlie Parker imports and seeking out others who existed on the margins of society. It was expected that I would keep my head down, get a degree in something sensible, like business, and come back to the suburbs to start a career in insurance. If I couldn’t do that, I was expected to end up a janitor in one of the local hospitals.

And I may have ended up back living in one of the Monongahela Valley towns until white flight pushed me farther east to a more rural suburb like North Huntington or Greensburg.

The Beehive changed that.

I had already found other kids like me at Point Park, but I thought that might have been a fluke. Once we walked into the South Side coffeehouse on a Friday night though, I knew I wasn’t alone.

The artwork was vaguely West Coast, and the customers had dreadlocks or dyed hair. They wore clothes like mine. They seemed slightly older, more urbane. It took about thirty seconds for me to realize I would be spending time at this place and the neighborhood where it was situated.

What I didn’t know was that the coffeehouse would become Pittsburgh’s center for the grunge and Gen X culture soon to become part of the American psyche. These people, in their ripped jeans, Doc Martens and cardigan sweaters were similar to those in the scenes developing in most large cities.

This cultural phenomenon happened without the internet, cellphones, Facebook, Twitter, Instagram or TikTok. It was almost completely free of cross-pollination from other cities, but it was completely consistent with what was occurring in Seattle, Portland, Austin, New York and most other large metropolitan areas.

It would sweep my generation into its vortex.

Like it did for so many others, the Beehive changed my life.

It changed the lives of many of the people interviewed for this book. It also changed Pittsburgh. It was partly responsible for establishing the South Side neighborhood as an artistic haven. Bands on local labels, like Blue Duck Records, not only frequented the coffeehouse, but they also performed at Club Café and the Lava Lounge, Nick’s Fat City and Graffiti. Shops like Slacker and Groovy appealed to those who were looking for underground wear and retro fashion. Dee’s Café provided cheap alcohol. Across a bridge and down the road, another Beehive and Slacker, located in the college neighborhood of Oakland, offered movies, poetry readings and coffee. Tela Ropa sold velvet day glo posters and bongs. The Avalon offered upscale but still inexpensive versions of the clothes found in thrift shops and Salvation Army stores, and the Upstage spun gothic and industrial dance music.

It would take another decade for Pittsburgh to become known as a travel destination for foodies or to start redeveloping its downtown area into a cultural nightspot with attractive loft living. Those changes can be traced directly to a coffeehouse in a neighborhood that was expected to offer nothing more to its out-of-work steel workers than a local shoot-and-beer hole in the wall where they could watch the Steelers, Pirates or Penguins sweat it out. The Beehive changed the energy of a city. It changed its DNA. It created a scene.

David Rullo is an award winning journalist and a senior writer at the Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle. His work has appeared in national and international newspapers, magazines and literary journals. He has spent the better part of five decades exploring and contributing to the city’s art and literary scene. Rullo’s work has been exhibited and heard in Pittsburgh’s cultural district and his bands Digital Buddha, Architects of the Atmosphere and Centrale Electrique have explored the boundaries between electronic music, spoken word, performance art and experimental music. His music can be heard in the score for the art film “The Pittsburgh Nude Project.” Rullo’s collection of poetry, “Tired Scenes from a City Window,” was published in 2015. A Pittsburgh native, he lives in the city’s South Hills with his wife and son, where he enjoys strong coffee, good bourbon and great books.

Leave a comment