Roaming: a column | somewhere between observation and critique | art and sound and movement by David Bernabo

Voice is the original instrument. So says my copy of Joan La Barbara’s 1976 album of extended vocal technique compositions. It’s a compelling argument, at least from a human-centric position – surely some prehistoric reptile heard musical tones emanated from wind passing through rock structures long before Homo sapiens started puttering around, starting fires and butchering turtles. But, yes, the use of voice for artistic expression has been around for a while.

Drums, too, are old. Rocks and bones are great instruments, especially when struck in a resonant canyon or cavern. Percussion is almost the original instrument or thereabouts. The Iowa State University Department of Music and Theater backs me up. “Drums, along with other percussion instruments were probably among the earliest instruments,” reads their webpage. “There is evidence that the first membrane drums consisted of naturally hollow tree trunks covered at one or both ends with the skins of water animals, fish, or reptiles.”

Personally, I’ve descended into a light obsession with percussion instruments. Starting with a Pearl Rocker drum kit in eighth grade, I’ve graduated to seeking out handmade instruments from Maine builder Jim Doble and the brothers behind Morfbeats. Glass and steel xylophones, essentially, and respectively. Slowly, I’m building dexterity with these pitched percussion instruments and finding ways to compose with them.

This pursuit has been aided by sympathetic drummers with a generosity to share their knowledge. Early aughts correspondence with percussionists Tim Barnes and Glenn Kotche opened doors to the music of Christopher Tree, Angus MacLise, and the Nonesuch Explorer series. Albums by Fritz Hauser and Han Bennink emerged from illegal downloading on Soulseek. And locally, here in Pittsburgh, a number of percussionists like Jeff Berman and Greg Cislon have directly informed my playing. Another of those local drum-based informers is PJ Roduta.

Roduta is an incredibly good musician. His four limbs have minds of their own. He studied with Milford Graves. He can play different types of music in different settings. He has multiple bags filled with items that, when struck, elicit a sound.

(We’ve been playing music together for over 10 years, off and on, currently in his group Else Collective and my group Watererer, so please know that this column is not objective. Honest, though.)

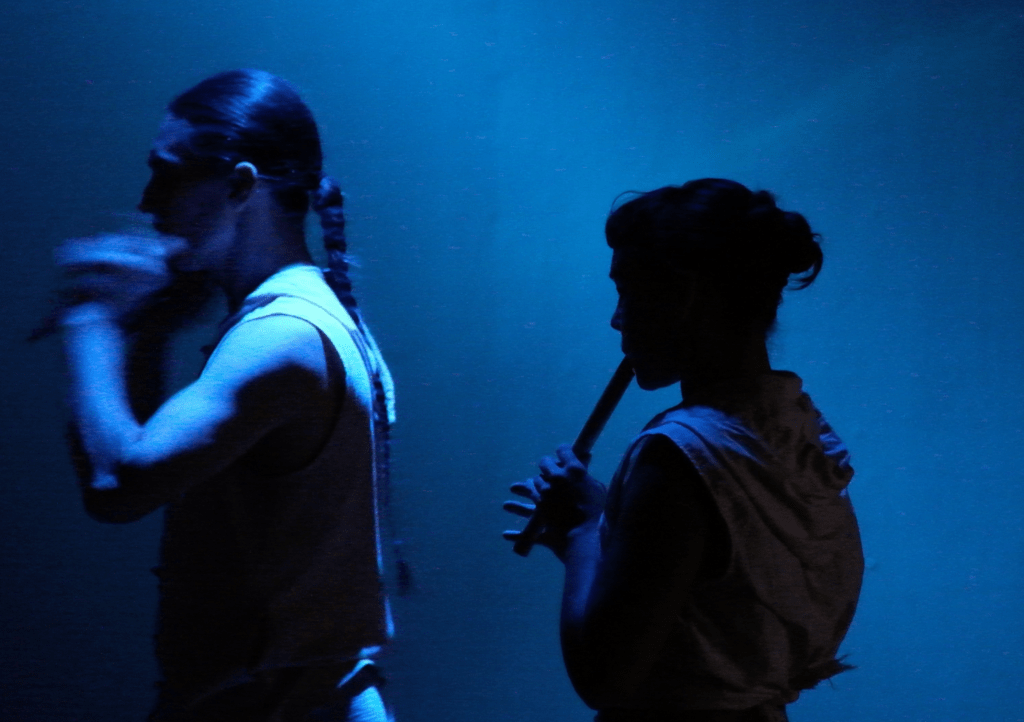

Terra Bubo is the latest project that involves Roduta. It’s a collaboration with choreographer/dancer/musician Renée Copeland. Copeland recently arrived in Pittsburgh from the Twin Cities, where she toured the world with Ananya Dance Theatre, co-founded the dance/performance-art duo Hiponymous with Genevieve Muench, and became a founding member and collaborator of hip-hop-based dance company BRKFST in 2014. Copeland is a triple threat, or maybe an n-threat, where n = dancer, choreographer, musician (flute, guitar, percussion), composer, and singer.

And despite these impressive backgrounds. Terra Bubo surprised me. I didn’t think it would be as good as it is. But it was damn good!

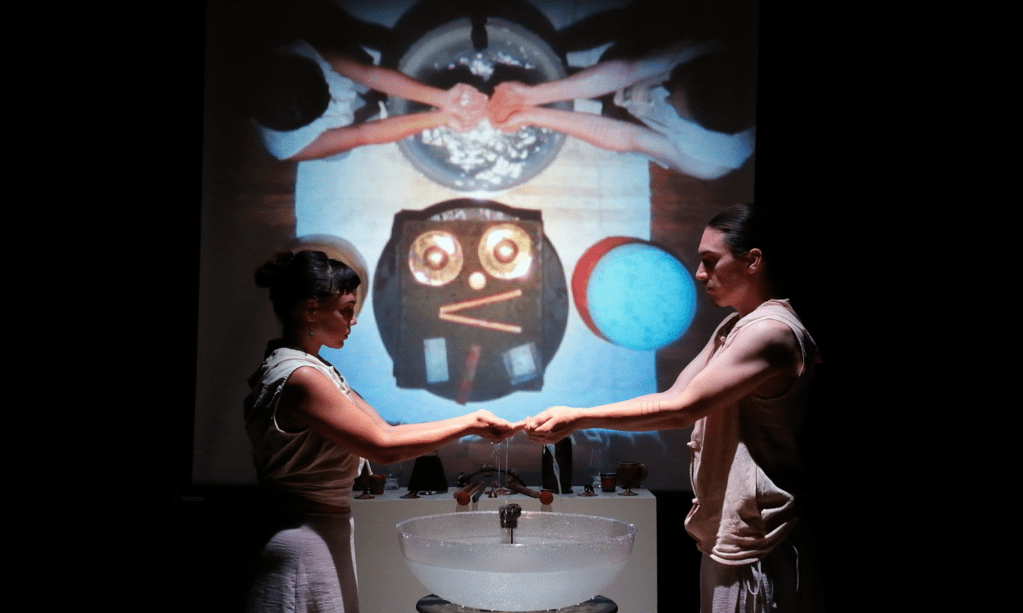

Percussion is front and center in Terra Bubo, an evening-length multimedia piece that for roughly 65 minutes presents a series of rhythmic scenarios – dialogues, maybe, paired with movement – that are interspersed with video and field recordings. Roaming across a series of minimal sets, the duo performs a marathon of complicated rhythmic patterns, all completely memorized, played on tamburello, bones, bodhran, gongs, and objects submerged in water.

The performance is steeped in ritual or at least the semblance of it. Shared movements and rhythms imply shared knowledge. Roduta and Copeland play in unison, then in interlocking rhythms, then in unison again. The work ebbs and flows. At one point, they yelp and parallel the drum rhythms with their voices. Later, they crash thick, wooden sticks onto metal gongs and plates at expert speeds, sending smaller metal objects dangerously close to the edge of the table. Halfway through the piece, there is a song – the beautifully-sung Irish traditional, “Samhradh Samhradh,” a song that dates back to the mid-1600s (or 1730s, depending on your source) and was more recently popularized by the band The Gloaming. And sometimes there is silence.

Compositions, instrument choice, and videos depicting water and volcanoes are in service to Copeland and Roduta’s research and reimaginings of their ancestors’ origin stories. Terra Bubo pulls from Sicilian (“earth”) and Tagalog (“spilled”). Land spilled. They take inspiration from the island nations of their combined heritages: Sicily, the Philippines, and Ireland.

It’s hard to tell whose influence is leading the three main sections. Copeland and Roduta often play in unison, somehow navigating an exquisitely complicated, but grooving chain of polyrhythms, clever accents, and varying timbres – mostly while each playing one drum or one bone at a time. Copeland certainly feels more at home with the movement, but both performers are so in sync and so committed to each note and each step that it’s difficult to assign either one authorship over any section.

As someone who a few hundred words ago admitted to a light obsession with percussion, I was enthralled the entire performance. But I did wonder how a non-endlessly-tapping-on-their-thigh audience member would react to the longer stretches of subtle rhythmic plays. For instance, there was a section where the duo was scraping objects on other objects in near silence. A few non-drummers told me that the section could have been shorter, but that, ultimately, they didn’t mind the length of it.

Speaking of length, the printed program for the performance was unusually thorough. Part of the length was taken up with detailed descriptions of the provenance of each instrument used in the performance. Now, I’m certainly one for liner notes, but I also like retaining a sense of mystery. Maybe this is why I promptly lost my program before I had a chance to read it (and why there may be a few inaccuracies regarding instrumentation in this review.) Moving on…

The performance ends with Copeland and Roduta encircling a bowl of water. Objects are struck and then dipped into the water, at which point the pitch begins to lower. A hydrophone (a microphone, coated and made waterproof, that amplifies vibrations instead of reproducing sounds in the air) sends these signals out into the room via an amplifier. Each trickle of water is audible and each submerged object makes a different sound, providing a nice contrast to the clacky and more arid-sounding compositions for tamburello and bone. It’s a nice close to the journey.

Splash. Gulp. Bloop.

David Bernabo is an oral historian, musician, artist, and independent filmmaker with a deep interest in local history and its repercussions on today’s Pittsburgh.

Leave a comment