by Emma Riva

You turn eighteen and in the United States of America, you’re an adult. You can vote. You could drive a car a few years before, but you can’t drink alcohol yet—though you probably already did. I was taught that there was a certain pipeline of adulthood. You’re a kid, you go to elementary school, then middle school, then high school, then college. Then you get a job. You figure out who you want to marry. You have children of your own. You retire. Then you die. Somewhere along the line, there, you own a house, maybe? I had plenty of examples to the contrary to look at, but this pipeline still instilled itself in me.

I look at my own life, though, and it makes no sense. I worked since I was a teenager and have had a wild string of jobs—teaching assistant, graphic designer, usher at a poetry club, research assistant for a zany but supportive professor, department store salesgirl, used bookstore clerk, tea barista, fundraiser for a foster youth advocacy organization, content writer for a travel YouTuber that’s been to every country in the world, literature tutor, college essay tutor, and along that ride “writer” as an umbrella term. (I would now say “art writer” if asked). I graduated college young, at the beginning of a pandemic, spending formative years waiting in line at urgent care and wiping people’s fingerprints off of the stair railings in the department store where I worked.

Everyone always told me I was mature for my age (even now, I’m hesitant to write exactly how old I am, because people always freak out). I prided myself on being more mature than my peers, advanced, somehow, morally superior. But I lived with chronic pain that made me more aware of the fallibility of my own body and more existentially troubled than most other teens or early twenty-somethings. Mental health-related turbulence in my family during my late teen years made me feel I had to emotionally fend for myself, but that didn’t make me more mature—if anything, I realize now that it set me back. I found a boyfriend I liked decently and we moved in together, another step on the conveyor belt, but it took a shock to my system in the form of attraction to someone else—spoiler alert, that didn’t work out either—to make me realize that I had just been play-acting adulthood because I thought it would somehow protect me from my own feelings.

I always think of the scene from the movie Ghost World with Scarlett Johansson and Thora Birch, where Johansson’s character shows Birch’s an ironing board in the apartment she’s looking at. “You gotta see this, isn’t it great?” she says to Birch, her face lit up with glee while Birch looks on unimpressed that her friend is starting to get excited about home goods. I felt similarly about finding out I had a device for hanging wine glasses upside down in my apartment. What exactly is being an adult? Is it becoming boring? How do you even know when you’re an adult? Does it mean getting married? Does it mean taking yourself more seriously? Are we all just doomed to only find excitement out of kitchenware?

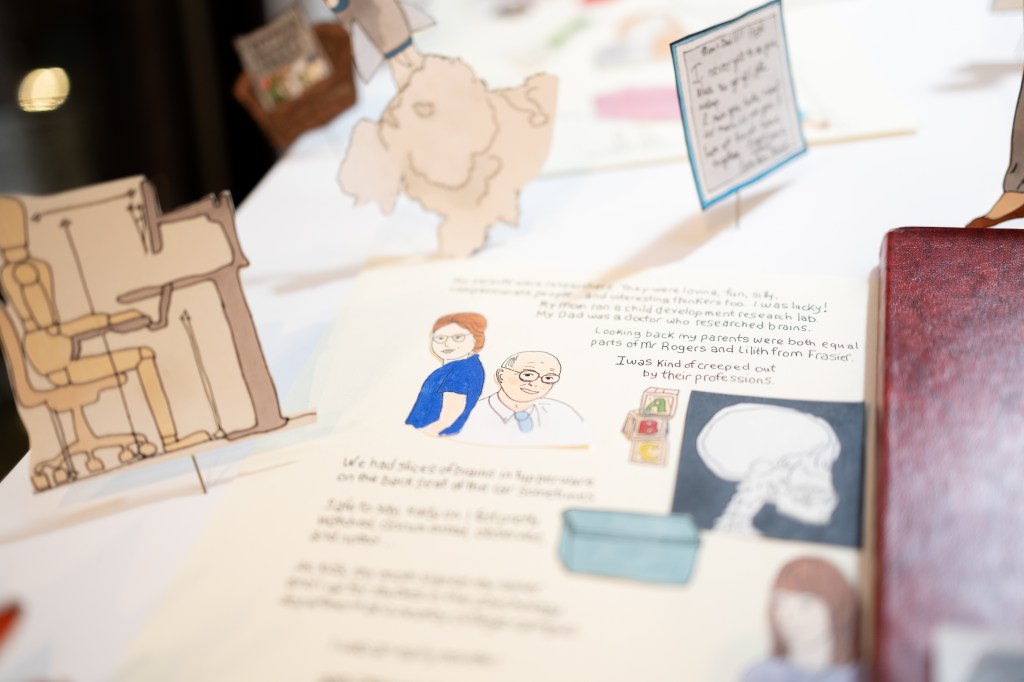

Georgia-based Filmmaker Amy Scatliff’s Adult Life Lab, which she presented at Ketchup City Creative in Sharpsburg this past weekend, engages with these questions about what it means to be an adult. There’s a stereotype about “adulting,” that it means doing mundane tasks like your taxes and developing back pain. But Scatliff thinks there’s something more complex at play and that so much of leaning into adult life is stepping outside of who your childhood authority figures thought you were. “You don’t get the freedom to control your time as a kid, but being an adult you get this kidlike freedom of time,” Scatliff said. “Being an adult is knowing that being an adult is a mystery.”

The film, photography, and social research projects around Adult Life Lab came out a lifelong interest in the human condition as the child of two medical researchers, but that upbringing came with its own set of expectations that she get a doctorate and fulfill maximum productivity. She was inspired by the concept of chindogu or “un-useless inventions” in Japan, starting with a “waiter-waver” she came up with to fix a problem she had waitressing back in her twenties: She would come over to take dessert away too soon, before guests were ready.

Now in her fifties, Scatliff took the concept of chindogu and applied it to adult life. What if we didn’t just put people on the conveyor belt and hope they were productive, but instead acknowledged that things are difficult, people are flawed, and while each of us has a different path, we are all trying to fulfill our basic needs. The “un-useless” or “silly” inventions might help us with things in our day-to-day lives that we feel silly for not knowing, simply because no one taught us and there is no one blueprint for how to be an adult.

Adult Life Lab is part documentary, part social research, and part DIY film. It’s also multinational, with a number of participants Scatliff met during a period of living and working in Turku, Finland alongside longtime friends from Minneapolis, students in Pittsburgh at Chatham University, and residents at a retirement community in Rome, Georgia. In total, it involved over 70 participants. In one part of the documentary project, Scatliff got the retirees to dress as the people their parents expected them to be. Marcia, one of the retirees, dressed up as a housewife for the photo Expectations and shared that: “growing up, the only sure thing about my future was I would become a college-educated housewife like almost all the women in my parents’ social circle. I see that this photo shows the underlying aspirations of women who may have chosen differently if more options were open to them.”

Another way Scatliff comments on adulthood was through a series of black-and-white clips entitled The Camera Never Lies showing people facing different challenges and asking viewers to identify what they were. The idea behind that clip series was to allow people to see their own behaviors from the outside and allow others to identify with their problems and see new things. She asks “If you spied on yourself, what adulting challenges would you uncover?”

Scatliff and I tossed back and forth different ideas about adulthood when we first met in person, as two adults at different life stages but with similar existential questions—one thing we landed on was that there’s a desire for stability, but that stability shouldn’t come at the cost of your happiness. Think unfulfilling monogamous relationships or an office job you hate, which offers stability but makes you unhappy and anxious. The stability from those things is, at the end of the day, illusory. “Stepping out of your comfort zone is something that will be in your life from age 8-108,” Scatliff added. “I worked with people in a retirement home in their ‘80s who have to change their lives when their loved ones pass away, I see people fall in love and date again in their ‘90s.”

One of Adult Life Lab’s findings is that people never outgrow the need for comfort. Comfort, ultimately, is what enables people to work through the challenges of “adulting,” and needing it doesn’t make you immature. Knowing you have someone to talk to, or to hug, and if not another human being, a stuffed animal or a pillow works. The radical idea that Scatliff proposes is that adult life or “adulting” isn’t really about mortgages or marriage at all, but that what helps you grow up is friendship and community. Adult Life Lab itself is the product of Scatliff’s supportive friendships—photographer Saul Portillo, cinematographer Kari Kylänpää, curator Jen Panza, co-producer Adam Heyes, and countless others.

There are certain realities that everyone faces, she purports, like paying rent and bills and feeding yourself, and through the community around you, you learn how to find a model that works for you to fulfill those needs. Getting an office job or getting excited about furniture doesn’t make you lame, but if all you can focus on is how well you fit into a box prescribed to you to be a real adult, you never get to know yourself.

There’s also a biological reality to aging, but that’s the only real, empirical metric we have of what it means to be an adult. We often focus on ways we might be different from other people, but the reality is that being alive, being mortal is the most communal experience of all. The mystery of being alive is something you have in common with every single person around you. Maybe it’s worth it to focus on that, sometimes, and Amy Scatliff’s work can help us.

Adult Life Lab is open through 12/10, with open gallery hours on Tuesday and Thursday. Amy Scatliff and I will be holding a discussion of adulting, DIY filmmaking, and what she’s learned from this project this Saturday (12/9) at 1:30PM at Ketchup City Creative.

Learn more about Adult Life Lab on their website.

Leave a comment