by William Repass

Tucked in a remote corner of the Fine Collection at the Carnegie Museum of Art, Arturo Herrera’s Night Before Last (1L) looks, at a glance, like the painting of a crime scene, if not a psychotic break. But the piece has a way of stretching glances into a gaze, and on closer inspection, it’s neither a painting, exactly, nor a scene, but a dreamlike condensation that tickles legibility, coaxing the viewer in.

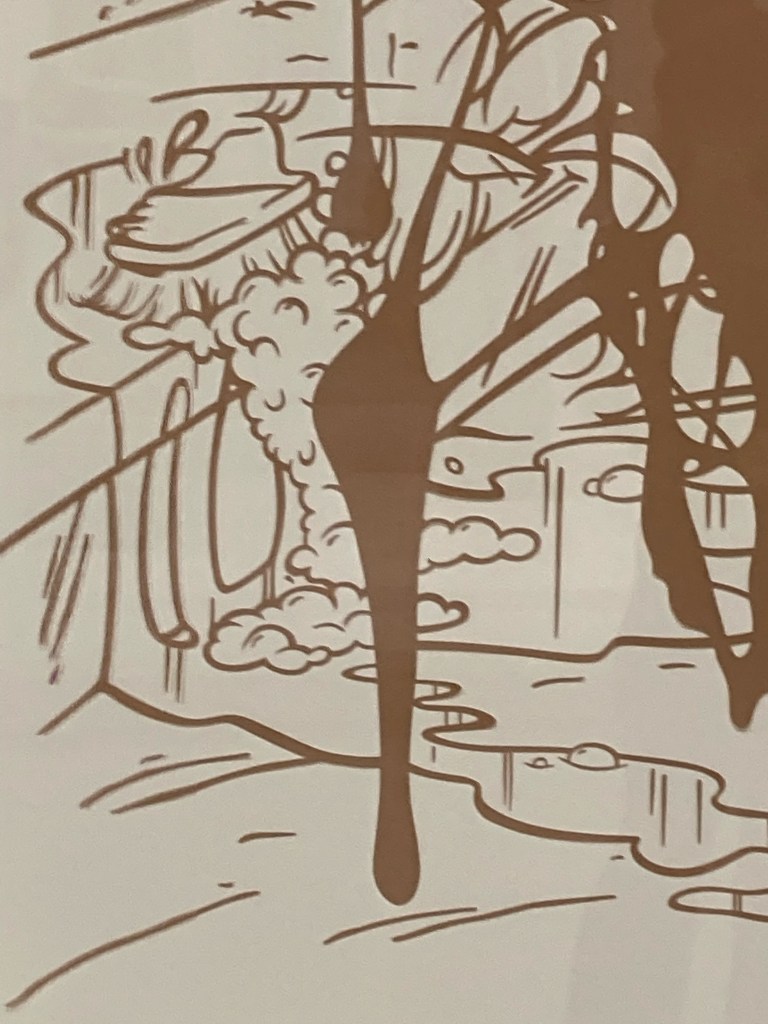

To describe the work as monochrome ochre against a white backdrop makes it sound simple, when it’s anything but. There’s the suggestion of domestic space, a bathroom or kitchen caught in harsh morning light. Is that a bed in the lower left corner or a sink? An oven door in the upper right, or a television set? An opaque blotch, the absence of line, or such a multitude of lines that they’ve congealed, obliterates the focal point. Soap suds or egg yolks, wigs or clouds of steam, emerge only to melt away again. These forms, tenuous as they are, don’t strictly consist of paint, but painted paper cutouts, not quite flush with the backdrop so that, when viewed from an angle, they cast discernable shadows.

Disguised as an action painting, Night Before Last is really a collage. Scissoring long strips of paper, presumably, requires a premeditation diametrically opposed to the methods of abstract expressionism. What’s more, collage disrupts perspective by making the piece literally three-dimensional, irrespective of the image it depicts, confusing a strict separation of foreground from background. At the same time, Hererra makes use of comic-strip devices for rendering perspective. Vertical lines, shorthand for reflections, turn a wavy-outlined splotch in the lower third of the piece, for instance, into a recognizable puddle. But he toys with this illusion of three-dimensional space demanded by realism, throwing the viewer into a vertigo of derealization. Not one line is rectilinear, even those appearing to depict the bedframe, the oven door. Anything that might gives the impression of solidity, under close scrutiny, softens at the ledges like a stick of butter left out in the sun. Swooping and tangling, outlines lapse into ooze, like the memory of a dream as it dissipates.

The use of ochre cannot but call to mind diarrhea, as if Hererra were poking fun at of action painting as a form of incontinence. Certainly, there’s a gleeful anarchy here, the pleasure of mess-making, squirting mustard from a squeeze bottle for no good reason. Chaos is the order of the day and the title, after all, suggests the aftermath of disaster or a party. The overwhelming impression is one of pareidolia—what happens when a random pattern of wood-grain or hairs trapped on the gleaming slope of a shower wall trick the mind into seeing grotesquely distorted forms and faces. The whole piece drips with indeterminacy, but it’s not without an almost childlike sense of humor. A banana-peel slipperiness that threatens both the pretensions of form and content with a pratfall.

Where comic-strips customarily depict action in a clean, economical manner, the messiness of Night Before Last is decidedly baroque. Its figurations bleed into one another, their boundaries porous (where there’s ooze, there’s a pore). Further, it’s possible to conceptualize the work as a strip, probably in the vein of Herriman’s Krazy Kat, but with all of its panels condensed in one, rendering the linear unfolding of action instantaneous. In evoking some past event, the title shores up this impression, as the act of remembering superimposes the past on the present. What we have here is the slapstick rupture of physics, also typical of comics, but Einsteinian instead of Newtonian physics. The memory (not of last night, note, but the night before) is no longer fresh, and in its decomposition, gaps open up for the imagination.

Night Before Last takes what we tend to think of as opposed—interior and exterior, subjective and objective, abstract and representational, past and present, artist and audience—and visualizes their interfusion. One way of looking at the work is to disentangle the chaos, parse it back out into a sequence of events. By design, that narrative would take a different shape for every viewer. In this way, the work supplies an open framework for interpretation, as opposed to a pre-digested “meaning” passed from the genius artist to an audience in the role of passive receptacle. As with democracy, the exercise of interpretation requires some effort, some close attention.

Originally from Los Alamos, NM, William Repass currently lives in Pittsburgh, where he works at a used book shop and an art house cinema. His poetry and fiction have appeared in Bennington Review, Word For / Word, Denver Quarterly, Fiction International, and elsewhere. His critical writing may be found at Full Stop and Slant Magazine. For links to selected publications, visit www.williamrepass.info

Leave a comment