by Emma Riva

What use is a title in a work of art? This question came to me while on a dreary morning shift in the Milton and Sheila Fine Collection as a Gallery Associate in the Carnegie Museum of Art. A guest brought up a piece I hadn’t given much thought to: Tony Smith’s Marriage (1962/1985). It’s a cast bronze and black patina shape and one of nine editions. A gate-like structure grows a third rectangle out of its left side. My eyes had glossed over it every other time I looked at it, but the title provided a narrative for what the sculpture might be trying to say. What was an abstract piece of bronze became a philosophical statement.

A much larger version of Marriage exists as a public sculpture. On the work itself, Smith commented only on its process, not its meaning:

“On Sept. 8, 1962, I made a drawing for a piece which I called The Wedding. This piece was never fabricated because I was paying off a loan I had made in order to do Die. It was to have had the same section as Free Ride – 16” square. It went in, up, over, and down. The opening was 6’8” wide, and the same deep. After doing the Elevens, I tried to put several pieces together with the same prisms. The boxes for Marriage were made in the fall of 1964. They were assembled in the spring of 1965, but the piece didn’t work. In the three-quarter view, the opening wasn’t visible, and the whole thing looked pinched. A new box, two feet longer, was made for the top. The substitution was made in the fall of last year.”

There is something kind of funny and ironic about a piece called The Wedding that was too expensive to make then resulting in a cheaper version called Marriage. But the titles led me to start speculating about the state of Smith’s marital life (it appears to have been fine? Kiki Smith turned out all right!) and add questions about the artist’s biographical experiences to my understanding of the piece.

In the case of Smith’s piece, the title is an unimpeachable part of the work and the piece doesn’t have the artist’s full context without it. Of course, you could choose to ignore that. Does that cheapen it? Since there are no words or figuration, a viewer has to come up with a narrative when they look at it. If Marriage were called Depression, or, even Divorce, it would undoubtedly change it. Or if it were titled, say, Black Rectangle #1.

Sol LeWitt did just that titling strategy with many of his paintings and sculptures. Open Irregular Pyramid (1986) is just an open irregular pyramid. It’s not Void or My Heart or Light and Shadow.

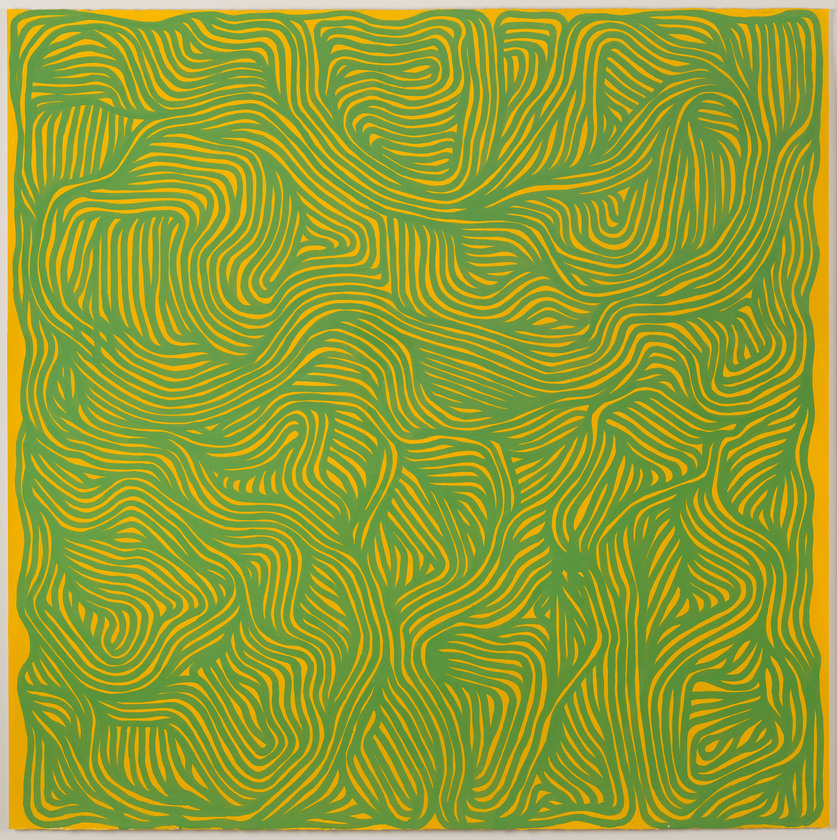

Irregular Curves (2000) is another example of the same strategy. LeWitt looked to the shape and the regularity of its formation for his narratives—what was notable to him was that the curves weren’t standardized but irregular. The wall text in the museum offers this quote from Sentences on Conceptual Art: “Once the idea of the piece is established in the artist’s mind and the final form is decided, the process is carried out blindly. There are many side effects that the artist cannot imagine. These may be used as ideas for new works.”

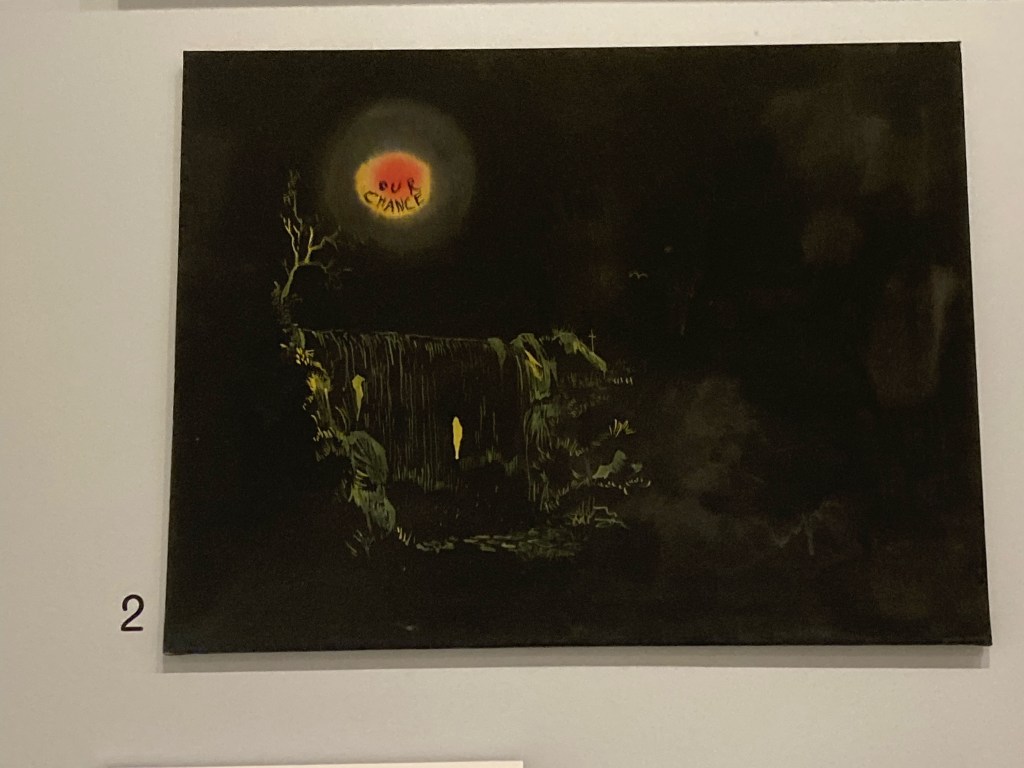

Another example from the Fine Collection: Friedrich Kunath’s Untitled (2006). This piece is deeply evocative and has a lot of potential narrative in it, but no guiding title. It would read differently if it were called Hope or My Parents’ Divorce or Suicide Attempt.

The title leaves you with nothing, which gives it an air of mystery. I’m proposing these alternative titles because it’s fascinating to me to consider how they change it and what we bring of our own associations to the art we look at. The question of whether you see hope or despair in Untitled is part of the painting. Is it about environmentalism? Is there a religious element to it? Its allure is part of its effectiveness.

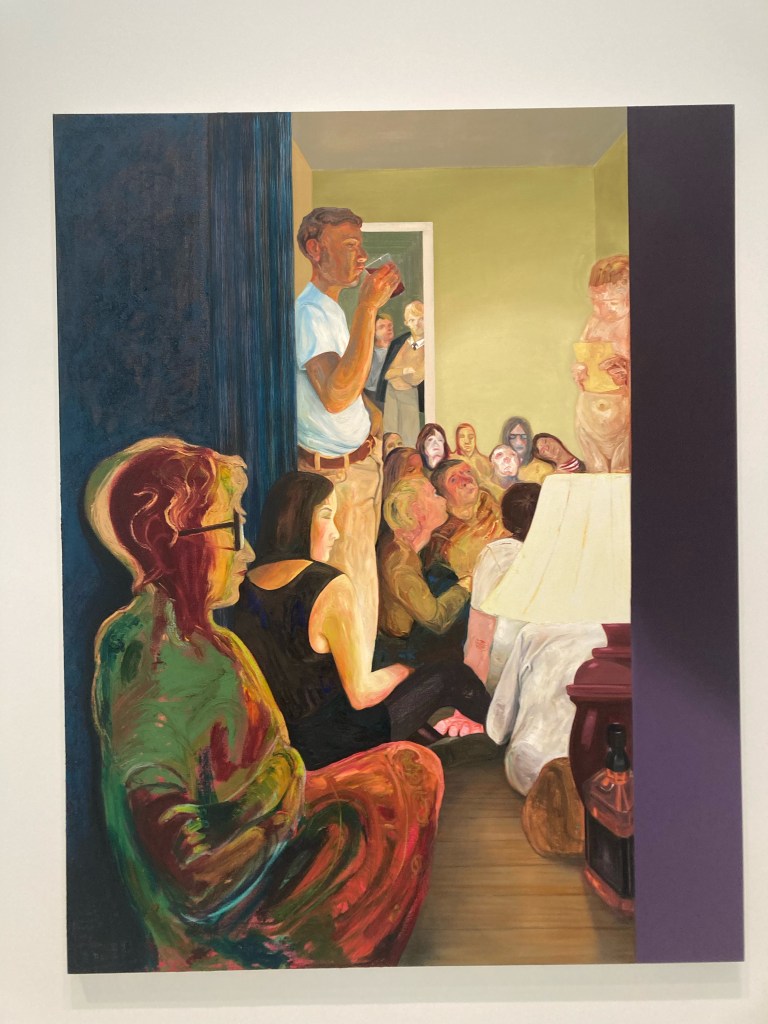

Let’s use one more example from the museum. Here’s Ariana’s Salon (2013) by Nicole Eisenman.

The title gives you something, but this painting has always mystified me. I read the woman, presumably Ariana, as being covered in blood–but this isn’t explicit. It’s unclear whether the figure holding the notepad is a statue or a real person, and why they are naked. Is it some sort of bizarre performance art? If it is a real human being, why does it look like a cherub? This title is unique in that it names one of the figures. According to The Washington Post, the painting is a tribute to Ariana Reines, who used to hold salon nights like the one depicted. (I’m uncertain if Eisenman herself said that, since WaPo doesn’t attribute it to her). Tying the painting to a real life figure takes some of the mystery out of it—before reading up on Reines, I pictured a debaucherous night gone wrong, the figure seated out of sight of the guests after a bloody encounter of some sorts, in the vein of the novel The Secret History.

I speak to guests about this painting frequently because there are so many potential stories you can tell yourself about it. It has clear characters you can cast. The more conservatively dressed man in the doorway, maybe shy about the naked figure. The couple in the back. The bottle of Jack Daniels in the corner. This painting invites stories about it, and the title serves as a literal title for the story. In my fiction program, we once took a trip to MOMA and wrote short stories inspired by pieces. Ariana’s Salon would be a great candidate for that exercise.

Maybe the title as Smith uses it is, ultimately, a gimmick. But it made me spend a lot more time thinking about the piece than I would have otherwise, and it’s something worth considering in your own work. Titles are a part of a painting, just as the materials, size, and composition are. They categorize and give meaning. The brain’s job is to categorize, and part of the artist’s job is to work through and around the associations and categories we all have.

Here are a few paintings by living artists in the Pittsburgh region where I invite you to think about what the title is doing.

Danielle Mužina, Not All 14th Century Rats

Oil and acrylic on panel, 2019

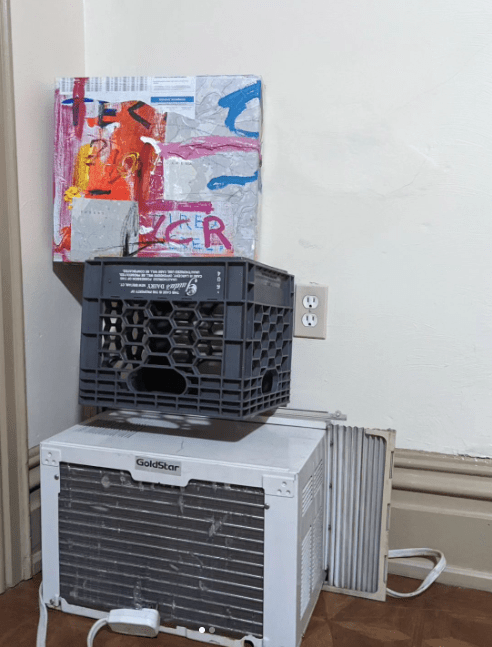

Grant Catton, Happily Retired in 35 Years in Accounts Payable

Acrylic on VCR, 2023

Lydia Rosenberg, Guys. Do we need as much money as we have? – GL

Lamp, hat. 2023

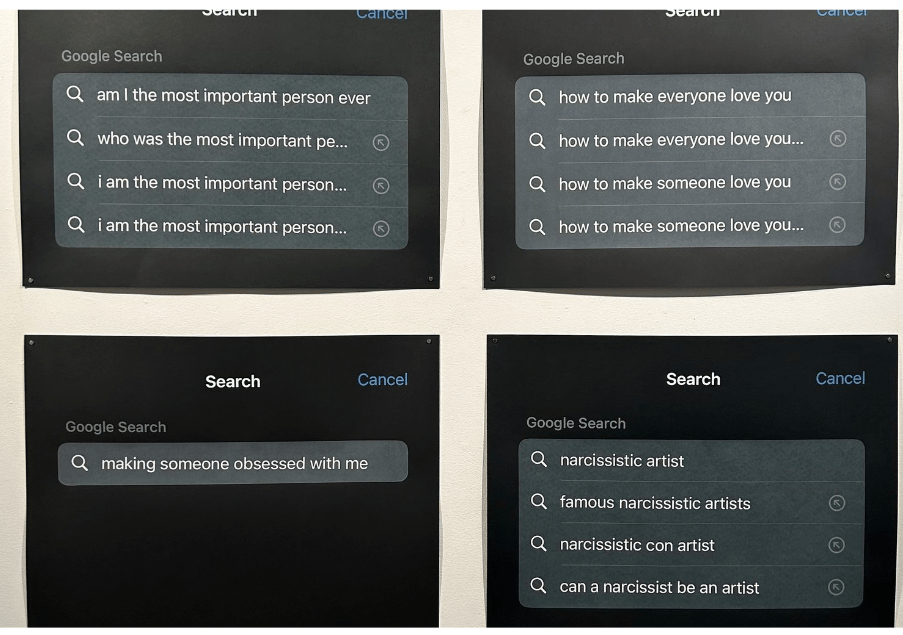

Tara Fay Coleman, Self-Obsession as Process, #1-4

Screen prints. 2023

Do you have favorite titles? Email, DM, or comment. This piece was a bit of an experiment into more of an arts-education-essay—I had a lot of fun thinking about this topic and would love to hear other thoughts.

Leave a comment