by Zach Hunley

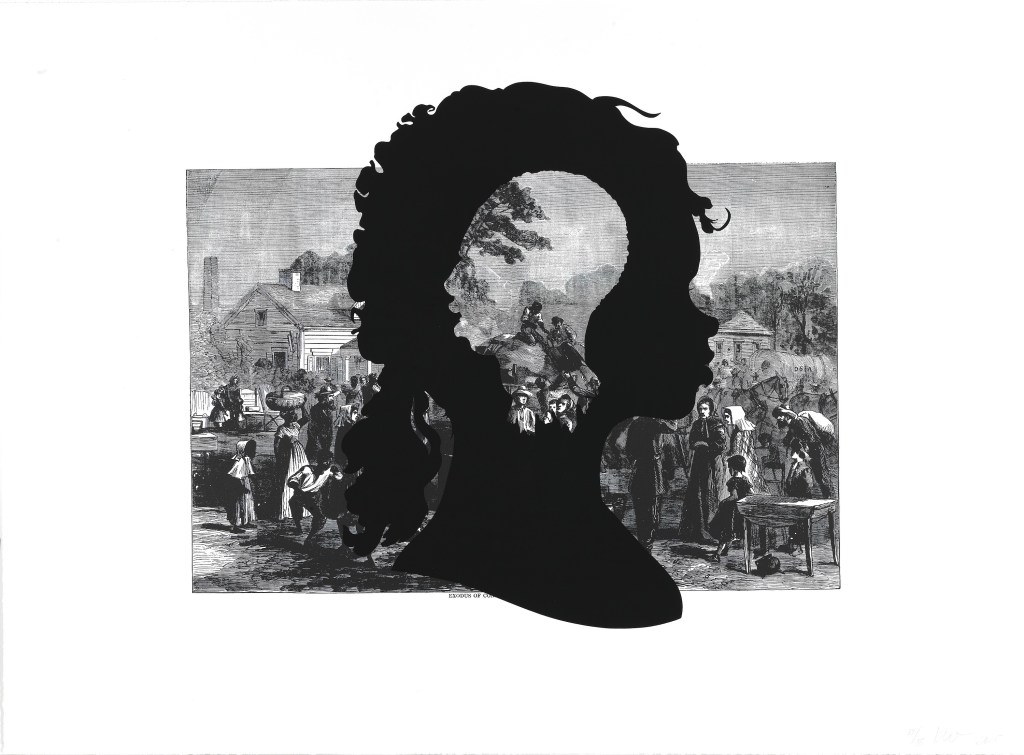

Cover image: Kara Walker, Exodus of Confederates from Atlanta, from the portfolio Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated), 2005, offset lithograph and screenprint on paper, 39 x 53 in. (99.1 x 134.6 cm).

The much anticipated exhibition of Kara Walker’s series Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated) has finally arrived to the Frick Pittsburgh, on view through May 25. The exhibition aligns with the series’ 20-year anniversary, and it packs a gut punch that urgently rings through to our current sociopolitical era. This resonance is not surprising, but what I did not expect was just how fresh these works would feel, as if they were made today. When viewing the work of Kara Walker, you are bearing witness to history and time compounded.

We are met with the kaleidoscopic Exodus of Confederates from Atlanta, tucked just inside the gallery entrance. This layered, double silhouette establishes several formal hallmarks across all the work: scale, perspective, and context. With Walker’s annotations looking in opposite directions amid the scene unfolding, the narrative becomes one of directional uncertainty. The maligned stares cast on the silhouette by several of the white onlookers is a genius way to further activate the scene through selective framing; in doing so, Walker’s figures become a presence to behold, a force to reckon with — impossible to ignore.

Walker’s portfolio of fifteen prints is accompanied from the outset by the historical basis for her work — original wood engravings on paper published during the American Civil War by the artist Winslow Homer for the titular publication, Harper’s Weekly. These prints are peppered throughout the three rooms of the exhibition, and are much smaller in size than the 39×59 inch works by Walker. Homer is considered a realist, and his depictions of wartime scenes of destruction and triumph, heroism and carnage stood as accurate depictions of these then-unfolding events. In truth, these scenes are fabrications molded by the wills of the editors at Harper’s and crafted almost entirely from the comfort and seclusion of the artist’s studio.

These documents, viewed in tandem with Walker’s re-presented interventions, reveal the role of historiography, the forces which shape the writing and proliferation of narratives and perspectives underpinning and informing the very structure of history. This act also speaks to the notion of an unreliable narrator, an issue central to Walker’s practice; her work prompts questions of who has been doing the telling, who should be, and who can be. Walker’s practice is a testament to the fact that you do not have to be a historian to have an active stake in the discipline.

To bring this point even further into the foreground, the Frick opened the door to a diverse network of local Pittsburghers — consisting of artists, arts professionals, cultural historians, educators, and leaders — and provided them the opportunity to offer their own take on the work through guest wall labels. These voices offer fresh context which humanize both their own perspectives and those of the artist. Every label felt essential to interacting with the work, which is a real accomplishment, though one pairing in particular stood out.

In Bank’s Army Leaving Simmsport, Walker’s annotation directs our eye to the periphery of the frame, past the boundaries of the orderly Harper’s image, which romanticizes the failure of General Banks’ Union campaign in the area. With her guest label, Pitt English Professor Shaun Myers directs us to look closer, highlighting a detail I had initially overlooked — a severed arm at the historical frame’s bottom left, added by Walker. Myers poses the question: “What else do you not see in this nation’s past?” For her, the selection of this piece was personal; Myers’ third great-grandfather, George Bailey, escaped from a plantation nearby to the scene in the etching.

Sharing the wall is Lost Mountain at Sunrise, a scene which Walker completely disrupts with her graphic annotation. The original printed image featured a single soldier overlooking the vast swath of southern land — a pastoral, romantic view of landscape. Now, at his back, rests the dark mass of an obelisk. The structure’s shadow collects at its base and outstretches in all directions; a child rests against the monument and looks in the opposite direction. With this new image, Walker reveals the fraught role monuments to the confederacy play in communities across the U.S., monuments which persist in the proliferation of historical narratives, and systems of power, as fabricated and as disingenuous (and violent) as the Harper’s images. Pitt Professor of History of Art and Architecture Kirk Savage’s words on this piece are worth lingering on.

Another aspect to Walker’s approach for this series that I found fascinating to consider pertains to the technical and formal implications of enlarging the historical images. The lines of the etching needle blur and are finely resolved at the scale they were published at originally; pulling these images to a scale as large as Walker does constitutes somewhat of an analog low-res image. Enlarging the etchings in this manner almost opens up the very fabric of the image, the structure of a history. In contrast, Walkers’ interventions are solid and unwavering, forcing viewers to interrogate the dissonance between the two planes — one firm and undeniable in its presence, the other becoming dissolved and unraveled.

In a way that may feel counter to the act of imposing a “new” image over a “historical” one, Walker’s work is in many ways about showing us what has always been there. It’s about bringing omitted Black histories out of the undepicted, unreferenced background and boldly into the immediate foreground. Through this action, she collapses the plane between the past and present moment, giving visual power, spirit, and voice to scenes where they were previously absent.

Silhouettes are the result of focusing light on a subject, from behind. In the context of Walker’s practice, that light is not only coming from behind the image, but frontally as well — emanating from our gaze as viewers in our contemporary context. The forces which informed history’s vision of the past rise to the surface of the picture plane, to meet those on the other side, ours, which will inform history’s vision of the future.

—

Kara Walker’s: Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated) is on view at The Frick Art Museum through May 25, 2025, with a free admission day being held April 2. Public events such as a book talk with Dr. Edda Field-Black (April 24, 7pm), an evening conversation between several guests label writers (May 1, 7pm), and more can be found on the exhibition webpage.

J. Zach Hunley (they/he) is a Pittsburgh-based modern and contemporary art historian, critic, photographer, collector of things, and proud father to a senior guinea pig. With a keen observational eye, they use their writing as a means to refract their deep appreciation for formal aesthetics through a socially engaged lens. They hold an M.A. in Art History from West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, and docent for the Troy Hill Art Houses.

Leave a comment