by Tara Fay Coleman

Photography by Sean Carroll

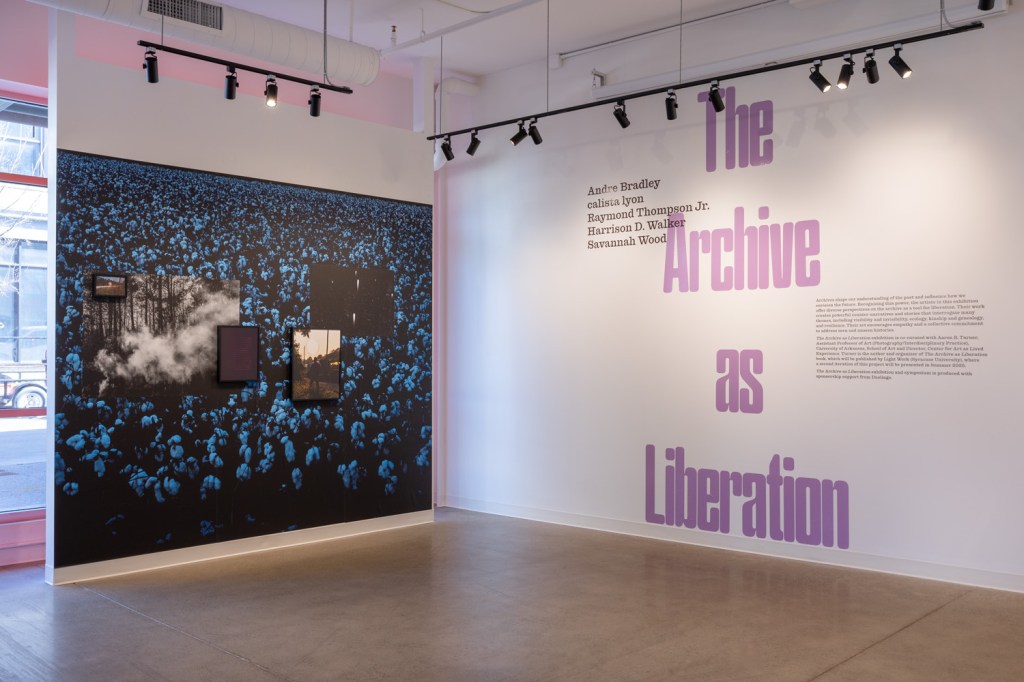

The Archive as Liberation at Silver Eye Center for Photography brings up a familiar tension, the kind that comes from knowing how easily stories can be erased, and how necessary it is to keep telling them anyway. This exhibition doesn’t feel like a distant, academic look at history. It feels like a reckoning, a refusal, a deeply personal kind of remembering.

Each artist here engages the archive not as a static repository, but as a living, shifting terrain where absence speaks as loudly as presence. There’s something especially powerful about seeing Black and Indigenous artists use the archive in this way. It’s stretched, re-written, and questions what has been recorded and what’s been deliberately omitted.

With the increasing push to delete demographic data and dismantle DEIA (or DEAI–I always go back and forth) structures, this work doesn’t just feel relevant, it feels necessary. As Octavia Butler reminded us in Parable of the Sower, “All that you touch, you change. All that you change, changes you.” These artists are reshaping the archive to imagine what could be, even as they wrestle with what has been.

Harrison D. Walker opens the show with a quiet but pointed provocation. His reflections on space exploration and the limits of visibility suggest a kind of speculative archaeology. His work feels in conversation with Butler’s vision of outer space not as escape, but as an extension of Earth’s inequities. In Walker’s hands, visibility becomes a question of who’s allowed to dream, and whose body becomes data, or debris.

From there, the audience is grounded by calista lyon’s installation, which shifts the conversation to land and extraction. While Walker looks outward, lyon looks downward and inward, into the soil of the Box-Ironbark forest in Victoria, Australia. Her work references the long, slow violence of colonization and industrialization; histories that linger in ecosystems and memory. Savannah Wood’s work provides a bridge between personal memory and communal inheritance. Through assemblage and film, she brings ancestral presence into dialogue with the present. Her layering of time evokes Butler’s approach to nonlinear storytelling, where past, present, and future are constantly overlapping.

Raymond Thompson Jr. picks up that thread and deepens it. His blending of photographs and archival fragments makes visible the gaps that so often define Black histories in America. But he doesn’t fill those gaps with speculation alone, he fills them with care. His work is meticulous, not in pursuit of perfection, but in its insistence that these lives mattered and must be remembered fully. I really loved the wall vinyls in the gallery. They served as a backdrop for Raymond’s photos and added a rich layer to the whole experience, making the space feel more alive and connected to nature.

Andre Bradley’s Where’s Walter? (Gentle on My Mind) brings the conversation to the urgent present. Created in response to the killing of Walter Scott, his piece is unresolved and devastating. It anchors the exhibition in the reality of state violence against Black lives, but doesn’t stop there. It invites us to reckon not just with what happened but with how we respond to it. In Butler’s world, survival is an act of community and imagination. Bradley echoes that ethos by creating a space of mourning that refuses spectacle, offering instead a kind of witness. I was drawn to the red wall surrounding Bradley’s work. The usage of color reminded me of how Octavia Butler used it indirectly as a signifier in her stories in order to warn us, transform us, or herald something new. In the exhibition, that red wall felt like a call to pay attention to what was on it and how we respond to it.

What I appreciate most about The Archive as Liberation is that it doesn’t try to resolve anything. Instead, it creates space for grief, questions, and possibility. It asks us to slow down and really consider what’s missing and why. In a time where the data that affirms our existence is increasingly under threat, this show reminds us that archiving isn’t just about saving, it’s about insisting, and claiming the right to be remembered on our own terms.

Right now, as history gets rewritten, vulnerable voices silenced, and essential conversations erased, archiving feels like an act of defiance. These artists aren’t just documenting the past, they’re making sure it’s remembered in the face of everything trying to push it aside. This work carries the weight of urgency, the kind that comes from knowing how easily our stories can be erased if we’re not paying attention. This exhibition felt like a reminder that archiving isn’t just about preserving history, it’s about fighting for what matters, ensuring that our truths survive, and that the stories of those often forgotten aren’t lost to time.

Silver Eye Center is open Tuesday – Saturday. Their next exhibition will be Fellowship 25, opening on May 8.

Tara Fay Coleman is an artist, curator, and writer committed to fostering critical dialogue in the arts.

Tara Fay Coleman is also a guest labelist in Kara Walker: Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated). This month’s articles are published with support from The Frick Pittsburgh for Kara Walker: Harper’s Pictorial History of the Civil War (Annotated). open through May 1.

Leave a comment