by Zach Hunley

Dear Readers of Petrichor,

On Friday, June 6, 6-9pm, as part of Garfield’s “Unblurred” gallery crawl along Penn Ave., PULLPROOF Studio will host a solo exhibition of new work by cofounder (and dear friend) Aaron Regal entitled move fast & break things. What follows is an essay reacting to the themes and ideas contained in this complex and timely body of work. Special editioned zines of this piece will be provided :–)

I hope to see you in person to celebrate the first, First Friday of summer!

– Zach

~~~

move fast & break things emerges from the unknown that surrounds the future of AI and art, amid an era of end-stage capitalism, techno-feudalist authoritarianism, and theocratic, oligarchic fascism. Aaron Regal’s affinity for the propaganda poster has trained his eye to cut like a knife through to specific sociopolitical moments, reveling in uncertain humor amid grotesque absurdity. His skill with collage confuses visual space and entangles conceptual meaning in a labyrinth of recursion. The result is new work which offers no conclusive answers, and proves there may not be any to find — before it’s too late.

To craft these pieces, Regal combines his visual language with that of the AI image, prompted and melded by his careful use of language at the terminal of Adobe Firefly, through the iterative process of creation, destruction, and re-creation. These generative elements were digitally collaged in Photoshop and grafted onto canvas via screen print to create the final, human made image. This is not “AI art,” but an artist’s experiment with new digital mediums made physical; looking at these works is to peer through a looking-glass that splinters and cracks at the sight of our reflection, as we complicate perception with meaning.

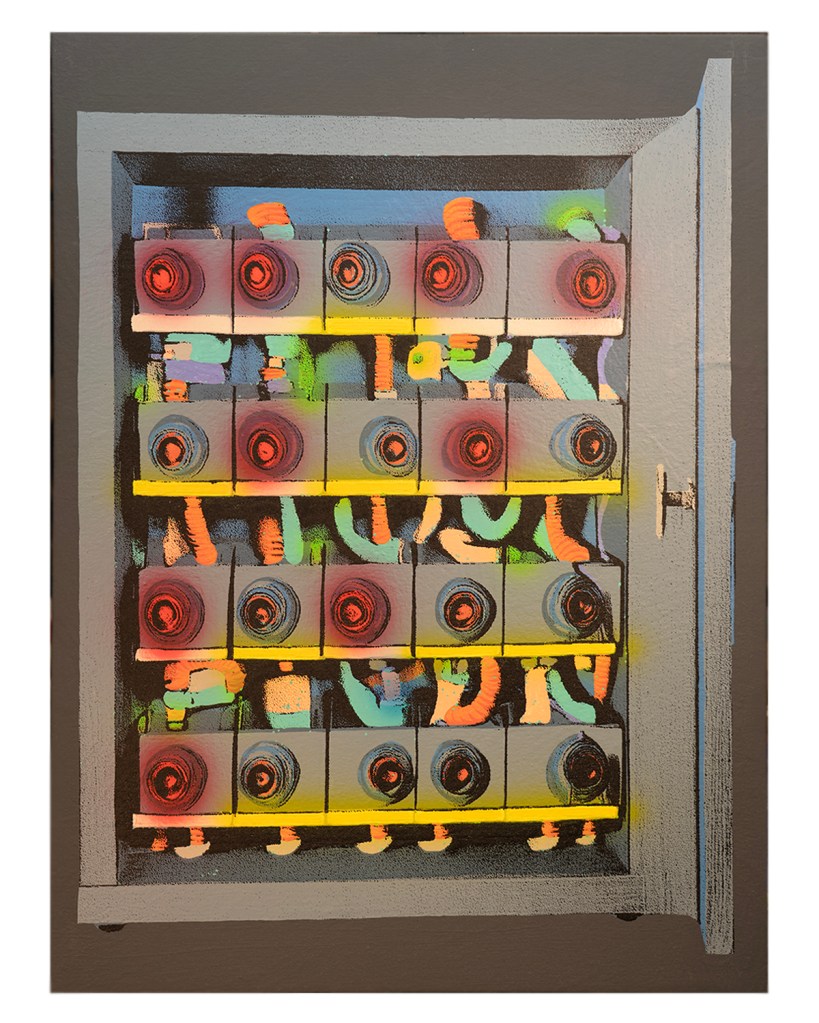

In Killswitch I–III, color emanates from the digital cogs of the machine’s backend interface, glowing and saturated, imbued with vitality from the feathered, misty veil cast by the airbrush. This is not a digital essence, but a warm, human presence — the energy of human creativity; human meaning; human life-force; a consciousness. It is slurped up by the computer brain, consumed and rehashed as it tries to make sense of what it is not. The product? A digital composite, a facsimile of humanity. For now, it is vomit; in a year from now, it may be truth. For now, Regal is still in control.

Internet Soup wryly deflates Warhol’s hallmark soup cans in the age of infinite image reproduction and re-presentation. AI generated commercial soup cans present as graphic iterations of each presumptive brand, like the abundantly stocked shelves of a virtual Giant Eagle. Attempting to read these labels makes language feel unreal. Some of these glyphic elements feel Cyrillic — the internet soup is cooked in a global crockpot. I think I’ll try a can of “Complees” this time…

As the saying goes: history doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme. The central focus of Walter Benjamin’s 1935 essay The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction is on the cultural import during the advent of mass media, and how this move to mechanical reproduction eroded art’s “aura” of unique authenticity, making the act of art making, in the context of capitalist society, inherently political. This essay was often discussed in my art history classes alongside an artist like Warhol, who himself was directly responding to the erosion of meaning and identity under consumer culture, something we are chronically exposed to today.

Absurd, unhinged AI advertisements are now the norm on social media, assaulting our subconscious mind with the soullessness of raw, late-stage capitalist consumption as we consume ourselves and our planet to death. We demand more, the data farms demand more; it’s a feedback loop spiraling out of control. AI masquerades as a magic trick, but that shroud is sewn from extracted and exploited labor, as data centers rely on rare earth minerals stripped from the Global South and content moderation is outsourced to traumatized and underpaid labor forces abroad. Once established in our backyards, the data centers consume our water supply and fry our already feeble electricity grids with the purpose of doing one thing: consume as much of our data as possible.

Benjamin notes: “…the mode of human sense perception changes with humanity’s entire mode of existence,” and “…the site of immediate reality has become an orchid in the land of technology.” Regal’s work reminds us just how far down this rabbit hole we’ve fallen. Our immediate reality has become slop in the land of AI tech; our mode of perception is mediated through the artifice of our laborious toil as workers in a new gilded era of entrenched wealth disparity and homegrown, state-sanctioned terror.

The seasonal still-lives illustrate our reality as it has become distorted through the veil of AI, appearing gloopy and radioactive. The vase in Spring reminds me of a Hieronymus Bosch painting; the inlaid orange, green, and blue circles recall Kenneth Noland — wait… is that a human heart? Autumn was in part prompted by the request for “a still-life of the land of milk and honey,” a literary allusion to the Old Testament descriptor for Israel. The result is a cum splattered bouquet and fruit platter amid a decidedly unimpressed smiley face.

Further uniting these four panels are expressive curvilinear formations that flow, arc, and weave throughout the scenes in a form of linguistic mark making known as Gregg shorthand. Developed at the end of the 19th century, mastery of this system allowed for writing speeds of up to 280 words per minute; now, AI is the latest tool prized for its near instantaneous speed in our ever accelerating world. Language itself, here the translated prompts which generated components of the works, is memorialized in memento mori as AI begins to speak for us.

Data Glutton, Bitcoin Revelry, and Whistleblower comprise a story in three parts. In the latter we see the image bifurcated spatially as two characters express dismay and shock over two bundles, tied up in golden fabric with creases that look suspiciously like human rib cages. Below, a group finishes their feast of what is presumably human flesh, only heaps of bones remain. What becomes of those who speak truth to power?

Bitcoin Revelry offers another view of the hedonistic get-together, featuring stacks and platters of golden disks being shared; the Bitcoin logo is lifted up like a communion wafer during Catholic mass. This visual stand-in for the digital currency appears like the spread of McDonald’s food Trump has served to guests at the White House. Those in attendance express looks mad with greed, their contorted faces revealing not one ounce of humanity — only blank, carnal consumption.

Data Glutton hammers this point with even more force, with the discarded stacks of empty plates and feverishly torn food wrapping now confetti on the floor. Bloated faces and blank expressions abound, while one patron seems to be asking for even more. A cross-shaped structure presides over the scene; our leaders of a supposed Christian nation indulge in the cardinal sins of ancient, biblical times. These are images of humanity’s downfall.

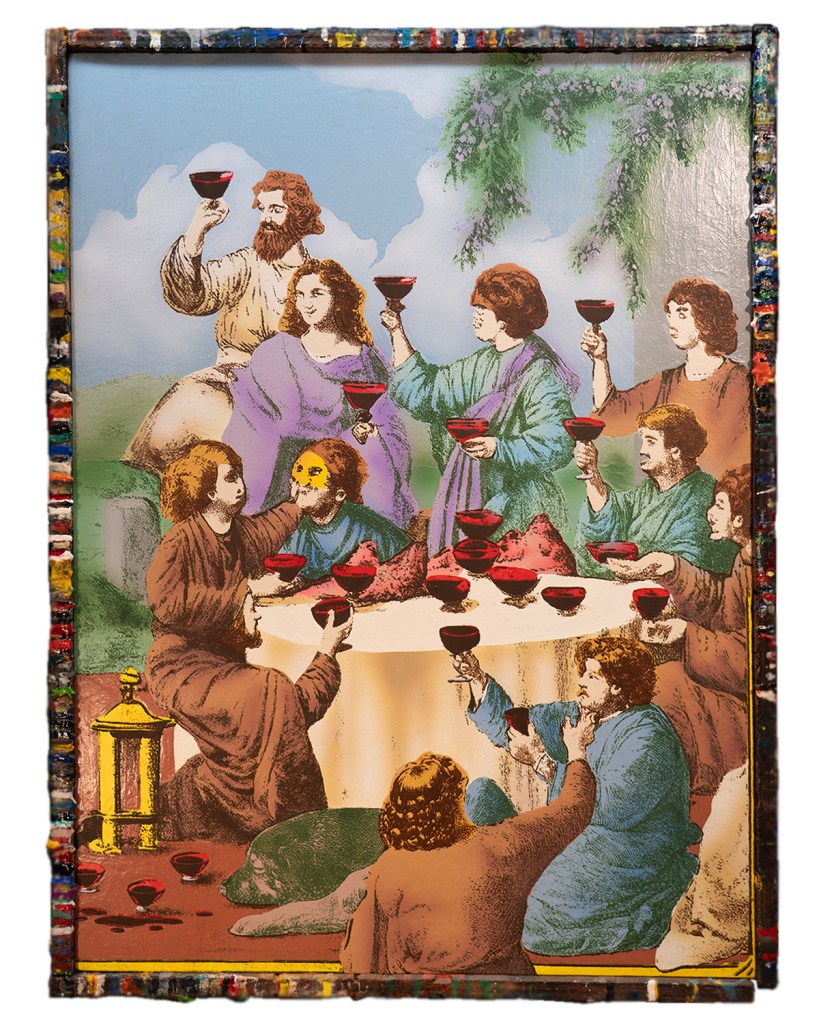

This triptych is brought home in Cheers to the Narcissist, a precursor to the day’s festivities that kicks things off with a toast of blood-red wine. Who precisely is the narcissist is unclear, but the top left figure clad in purple makes a direct and sharp glance at us viewers, casting a slyly sinister smirk, implicating us in the scene. Are we the narcissist? Or have they just conned us into letting them take over systems of governance and socioeconomic control? Surely the newly bro-ified Mark Zuckerberg thinks very little of himself…

The hallucinatory visual style of AI images is also seen in these works, something Regal sought to capture before the models refine their training to the point that their replication is indistinguishable from observed reality. Most of these details are comically peculiar — the conjoined figure in Cheers… is one example — but also reveal concerning implications as AI slopaganda morphs to meet the ideological ends of its creator. Regardless of its veracity, the content is shared via the same apparatuses alongside the real and the urgent. As Nesrine Malik wrote for The Guardian, “Even when the content is deeply serious, it is presented as entertainment or, as an intermission, in a sort of elevator music.” AI content delivers no solutions, just complacent, zombified subjectivity. In this way, the aesthetic of AI can be seen as the new aesthetic of fascism.

Bricked iPhone [In Search of Higher Resolution] is a vanitas that distills down some of this exhibition’s most salient conceptual underpinnings. Alluding to Regal’s practice as both printmaker and painter, an easel acts as a springboard for a bouquet of flowers, some tomato-y looking oranges (or orange-y looking tomatoes?), and a decapitated head resembling a certain aforementioned tech CEO, his eyes animated and his cheeks swollen with excess, crumbled like the remains of a Roman Imperial bust. “BRRKD” reads the phone screen, glowing neon red — game over. To the right, a stack of four squares mark the artist’s struggle in working between digital and analogue inputs. While our digital interfaces produce images at an ever-increasing pixel density, what compromises must we make to bring the digital into material reality? What are we truly searching for? How in the world can we find it?

To return to Benjamin, he cites an earlier essay from 1928 by Paul Valéry, The Conquest of Ubiquity, which posits more accurate generational forethought than most of our overworked, attention span addled minds can conceive:

Just as water, gas, and electricity are brought into our houses from far off to satisfy our needs in response to a minimal effort, so we shall be supplied with visual or auditory images, which will appear and disappear at a simple movement of the hand [or the finger, swiping on the screen], hardly more than a sign.

The age of mechanical reproduction has given way to the age of endless virtual reproduction. Our data, mined by the tech oligarchs like an invaluable natural resource, is processed, canned, and labeled for our own consumption. Don’t like it? There’s an endless supply… It costs nothing but you and me.

—

J. Zach Hunley (they/he) is a Pittsburgh-based modern and contemporary art historian, critic, administrative professional, photographer, collector of things, and proud father to a senior guinea pig. With a keen observational eye, they use their writing as a means to refract their deep appreciation for formal aesthetics through a socially engaged lens. They hold an M.A. in Art History from West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, and docent for the Troy Hill Art Houses.

Leave a comment