by Zach Hunley

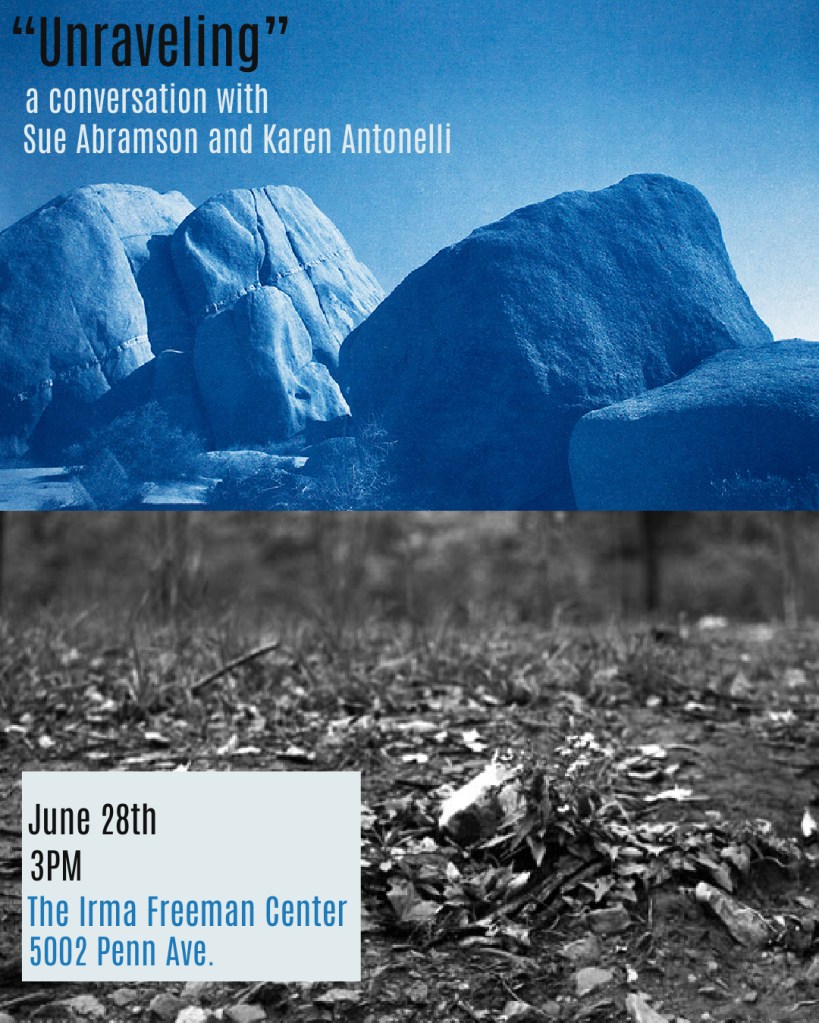

During June’s First Friday I ducked out of the scattered rain into the Irma Freeman Center for Imagination, and was greeted by a wall of stunning, large format cyanotype landscapes amid complex and moody carbon prints. The exhibition, Unraveling, presents the work of two legendary Pittsburgh photographers — Sue Abramson and Karen Antonelli.

The work tethers its theme to varied views of land around the world, from Joshua Tree to Loch Ness, documented by the artists and reproduced through complex, physical mediums. The result is a body of work that captures and materializes the spirit and essence of unraveling. As Matthew Newton writes in his vividly expressed statement for the exhibition: to unravel is to disengage from reality, head over heart. It happens all around us, and all the time. It’s emotional and unseen.

Ahead of the show’s closing conversation between the artists on Saturday, June 28th (3pm, IF Center), I had the pleasure of speaking with Sue about her memory of landscape, the historic photographic mediums used in the exhibition, and her life as an artist in Pittsburgh.

—

Zach Hunley: Looking at these photos, I wanted to ask: what is your earliest memory of landscape?

Sue Abramson: I have been going to the Jersey Shore since I was a baby, and so I feel those places are really my earliest memories of the expanse of ocean. I went to summer camp in the Adirondacks, on Raquette Lake, and I feel like that is truly where I learned to love landscape, nature, and the outdoors. That’s where I started taking photographs, too. I grew up in Suburban Philadelphia, so it wasn’t the city; there was a park down the street from my house, so I spent a lot of time there, too, but Raquette Lake is really what sucked me in.

Z H: How has your relationship to landscape shifted across your practice over the years?

S A: Beyond this work here, for the last forty-some years, I have been going into the woods regularly and photographing. I started doing that when I was in art school, and I think initially I was attracted to light, and how film recorded light and shadow. My first photographic work that I took seriously was related to photography almost as much as it was related to the landscape. When I moved through that, I became more interested in the trees and the chaos of the plants growing up in and around the woods. I was really aware of how dense east coast forests are, as opposed to the west coast where there are massive deserts and a greater sense of scale. It was more about detail. I then started to get into more specific things like wildflowers, specific plants growing in nature, and then I went back again to just looking at everything as form. I’ve always been in the landscape for any kind of adventure or vacations; most of the time that I would take some time off I would be going into nature. That’s where I photographed more traditional views. A lot of my work is close to home — in the garden, in the woods in Frick Park — and this is the first body of work where I really do exhibit more traditional landscapes that I found in spots not related to Pittsburgh, like both coasts, the desert, and the ocean.

ZH: To bookend my first question: what is your most recent memory of landscape?

SA: I think it’s Cape May, the Jersey Shore. My family always went to Atlantic City in the summers, but recently my son and I started going to Cape May, partly because it has a lot to offer, but also because it had no associations with family vacations. So we created our own, new, family memory of a place to go to that didn’t have anything to do with previous generations. We go there twice a year, in May, it’s a mother’s day gift to myself. That’s where a lot of these carbon prints come from. Almost every time we would go, there would be a hurricane or a tropical storm right before. In September we go to see the monarch butterfly migration, and there’s almost always a hurricane right around the time we’re going. I started to realize that almost every experience I had with the ocean now comes with some massive storm. The climate crisis and all the “once in a hundred year” storms that happen every year become more and more real. So I decided I would start photographing the evidence after the storm, and relate my work to those themes of climate change and just general change in the environment.

ZH: How has the landscape of the Pittsburgh arts scene changed through your eyes in the decades you’ve been a part of it?

SA: Things have changed. I was so involved with Pittsburgh Filmmakers and Silver Eye, though it used to be called Blatent Image and it was in the South Side. I feel like there has always been some place where I could fit in and show my work. I think the arts scene along Penn Avenue has been the biggest change, and the south side used to be so “up and coming” and then it just disappeared. It felt like that’s where it was all going to be, and now it’s all along this corridor. I think it’s fabulous because there are so many opportunities for people to exhibit their work. I’m so in it, so it’s hard to have perspective. Things have closed, like the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts, which is a real loss to the city. But there are lots of cool places opening up all around. I like the movement.

ZH: I was really moved by the cyanotypes in this show. What do cyanotypes do for landscapes that other mediums don’t?

SA: I think that it puts everything into a historical context, because it is a 19th century process, and all landscape is historical. I really like that aspect of it. It’s also kind of romantic, because of the softness. I don’t brush the emulsion onto the paper, I use a glass rod to push the emulsion on the paper. I want you to get the sense of handmade. I love the hand quality to it. That blue is inspiring and visceral. It makes me hopeful. When I look at photographs I like to relate them on both visceral and cerebral levels. If the photographs don’t get me in the gut, then I’m not as engaged. The rocks at Joshua Tree, those blues are just crazy to me. The process tends to be very high contrast, so to get full tonal range with mid-tones, I work very hard to get that.

ZH: Are you always photographing, or do you set aside time specifically to work?

SA: I set aside time. I do use my phone as a sort of sketchbook, so I do photograph with that, but I definitely set aside time and go to a specific place to photograph. The carbon prints in this show are all phone photographs. Underlying a lot of this work is the notion of extremes — it just seems like that’s where we’re at now as a society. Because of the extreme weather conditions I started to become interested in pairing the phone — the simplest point and shoot camera there is — with the most difficult 19th century printing process I’ve ever tried, so the whole process became extreme. That’s a private work ethic for me — I want to keep those extremes in there. The cyanotypes are from enlarged digital negatives that I adjusted the contrast. I still shoot on film, too. I try to mix it all up.

ZH: Which of the processes you use is the most difficult to work with?

SA: The carbon print is the most difficult. Partly because it’s not really done much anymore, so there are no materials provided for making them. You used to be able to buy the carbon tissue, which is just a substrate covered in black gelatin, but they don’t make that anymore. I started doing the process with Melissa Catanese, we bought textbooks and started making our own carbon tissue. We did so much experimenting only to make so many mistakes. We made mistakes we didn’t even know we could make. And then when you thought you had the process down and started to get a little cocky, the next print would be a total failure. Even now I’ll go in with confidence and it will end up a failure. The used tissues are typically thrown away, but they are so cool looking, so we started saving them all. Four of the prints in the back room are prints from the tissues. There wasn’t a lot of guidance, so we just had to experiment for years. It’s a fascinating process and it was fun to collaborate with Melissa. Being a photographer can be so isolating.

ZH: How do you and Karen consider the relationship between your work in this show?

SA: We have both always been interested in photographing nature and not just “beautiful nature.” We did studio visits and shared the work we were doing. Karen has so much work and so many different bodies of work, and I feel like she was the one who chose work that went really well with my recent work. We are both really fascinated with the notion of the surface — of the earth, the soil, and what’s underneath. There’s so much that you can’t even see. I feel the same way about the ocean. You see the surface, but there’s so much underneath. We both have similar feelings about the work.

ZH: How did this show come about?

SA: Karen and I had been talking about showing our work together for a really long time. For whatever reason, none of the previous versions happened. We were talking about wanting to do a show here, and Sheila asked us to do a show. She initially asked me to bring the Uprooted show [in AAP’s 109th Annual, Transcendental Arrangements, Miller ICA, 2023], but then I realized I had so much cyanotype and carbon print work, so I decided to not include those older works. After I’ve accumulated enough work, I want to get it out there. So much of my process is experimenting and sitting with it for some time, until I figure out how to create a show.

ZH: What do you hope those attending your closing talk will take away?

SA: More of what I’m thinking about when I’m taking the photographs. I don’t really like to tell people what to think; I don’t want to lecture anyone in an artist statement. I don’t really always know what people take away from it. I would like to talk more about the extremes. The last three cyanotypes are the most recent, I shot them last year in Scotland, and I found a bit of humor in the work. The one in the middle is a rock, but, because of the way I shot it, gives an interesting sense of scale to where the rock almost looks to be the size of the mountain. The last two are Loch Ness, so there I’m searching for Nessie. I get so heavy when I talk about the spotted lantern fly and invasive species, and hurricanes and massive storms, so I wanted to add some lightness to it. We both want to talk about unraveling and how we are both seeing nature and the ecosystem unraveling. I asked Matthew Newton to do the statement because I feel I can eloquently make my work, but I don’t really like the way I write. I wanted there to be some similar eloquence in the statement as in the work.

—

—

J. Zach Hunley (they/he) is a Pittsburgh-based modern and contemporary art historian, critic, administrative professional, photographer, collector of things, and proud father to a senior guinea pig. With a keen observational eye, they use their writing as a means to refract their deep appreciation for formal aesthetics through a socially engaged lens. They hold an M.A. in Art History from West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, and docent for the Troy Hill Art Houses.

Leave a comment