by Emma Riva

Whatever you see in Fabrizio Gerbino’s paintings is correct. He told me as much: “Anything you see in the painting is right.” More than anything, his work inspires curiosity, because he made it with curiosity. Gerbino has an inherent curiosity and wonder about the world around him that comes through in his paintings and sculptures. He interrogates each subject from every possible angle and iteration—case in point, he created an installation, then made a series of paintings of the installation after the fact in different shades of grey and green. “I like to have a different experience every time I paint,” Gerbino told me in his McKees Rocks-Stowe Township studio. “You build the story of the painting from the process. The painting comes from the experience.”

Though his vision is expansive, Gerbino has the consistency of a seasoned painter, particularly in his color work and his composition. His color palette is greys and greens, only rarely veering into red. The tones reminded me of filmmaker Stan Brakhage’s drawings on film reels, etchinGs of dreams over soft flares of color. Many of his paintings use contraposition, where an object at the back of the field of vision is softer—feather-like, cloud-like brushstrokes—objects at the front are sharper and more structured, with the quality of metal or stone.

The images have a dreamlike quality, like a Polaroid or film photo. Gerbino found inspiration in the fact that when he transitioned into a digital camera, he couldn’t figure out the lens, and the camera kept flashing the line “This picture cannot be played.” Gerbino found the wordplay interesting. Rather than getting too frustrated at the glitch, he painted it. Likewise, when he was at the paint store, he didn’t go for the buckets of paint that were actually for sale, but instead was fascinated by the swirls of color in the discarded paint bucket. These became a series of kaleidoscopic color studies on 72 x 72 canvases.

Gerbino’s art surrenders to the mystery of life, that even in things that seem mundane, there’s a lot of the unknown. saw a lot of Swedish mystic painter Hilma af Klint in his work, his interest in huge canvases with uncanny, evocative shapes—and in swans. During a residency where he spent time at an abandoned zoo, the only animal he saw remaining was the swan. He painted the swans as flickers in deep green color fields, provoking questions about whether the swans in the abandoned zoo are captive or free. They float on the painting’s midline, ghosts, glimmers, or signs of life.

“I go past the original function of objects and use my imagination,” Gerbino explained. This is fitting for his studio, an former church that he and his wife Cynthia Lutz work out of. They left some of the pews in the chapel, so Gerbino’s canvases are surrounded by dark red chairs without occupants. The Sto-Rox area, where Lutz is from, is another object of fascination for Gerbino. He and Lutz met in his native Florence, and they moved back to her hometown. What was standard post-industrial architecture for Lutz was entirely new for Gerbino. The American landscape was unfamiliar to him, so some of the first paintings he did in Pittsburgh were studies of the skyline.

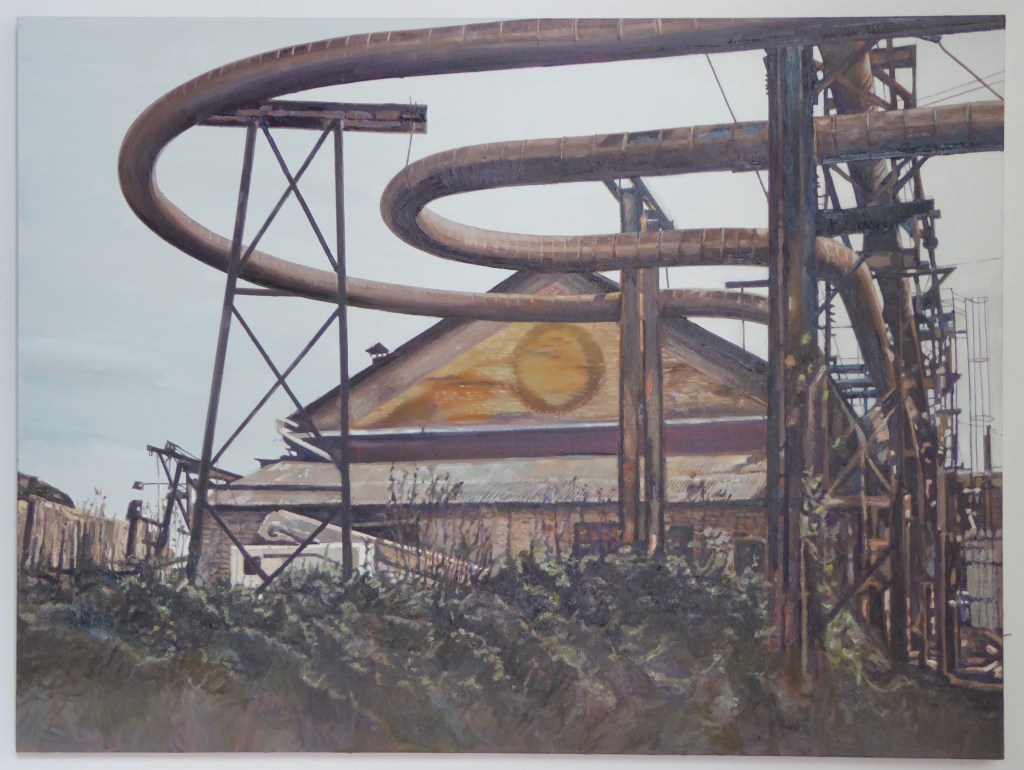

That evolved then into paintings made for Factory Direct, a 2012 show at The Warhol that challenged artists to do residencies in Pittsburgh factories. Gerbino worked with the Calgon Carbon Corporation and fell in love with using activated carbon as a material in his paintings. Many of his paintings now use it, even long after the fact. Nearby his studio on Neville Island, he turned his eye to the Shenango Factory on that odd, somewhat noxious strip of land in the center of the Ohio. Gerbino has painted quintessentially American industry sites with the curious eye of an outsider, finding beauty and simplicity in dilapidated rooftops or smoke-stacks. Where some “post-industrial” art reads as sentimental, perhaps it’s Gerbino’s outsider’s eye that gives his paintings of the coke plants and waste production sites more space to breathe.

Though these industrial paintings are more literal, Gerbino is careful to not describe his paintings as fully abstract or figurative. When I pointed at a painting of blue squares laid out on his studio floor and described it as abstract, he remarked “That’s figuration—those are tiles from underneath my floor!” The changes in scale and the appearance on a 2D canvas render otherwise recognizable objects into a sort of mystical form. “I want to make these things monumental,” he said, gesturing at a painting of dresses thrown into a dumpster in McKees Rocks. He quoted Giorgio Morandi’s statement that “Nothing is more abstract than reality.”

The unsentimental quality of Gerbino’s work applies also to places of suffering and despair. A recent series depicted empty beds at a homeless shelter and makeshift roofs at a refugee camp. He was interested in the repetition of the patterns in photographs that he saw of each place. The resulting paintings are eerie, showing how dehumanizing and sterile each of the spaces are. But the painting does not perform suffering and tragedy. Its strength is in its coldness.

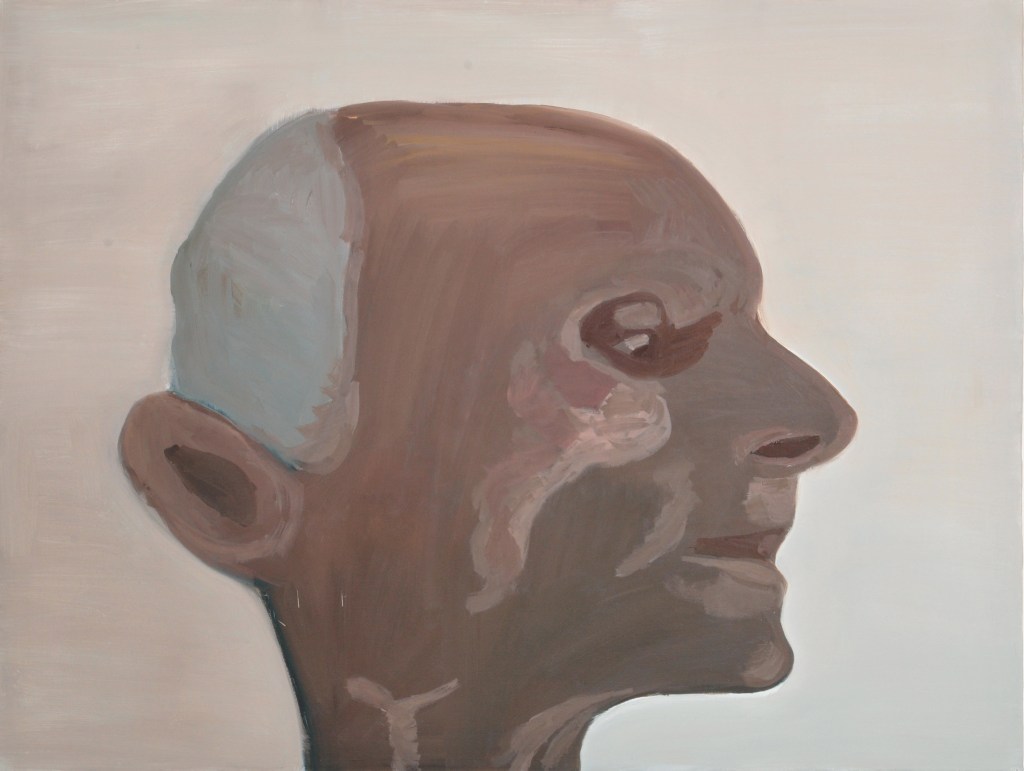

Gerbino’s paintings are mostly called Untitled. Only in a few cases—a painting of his father’s face, some industrial paintings—does the title give you any indication of the painting itself. Like af Klint or other painters working from curiosity, Gerbino’s paintings bring us closer to the wordless truths at the heart of reality.

Gerbino will soon be bringing some of his industrial paintings to the Associated Artists of Pittsburgh show Brooklyn X Pittsburgh: Industry of Art that opens on July 19, juried by Eric Shiner, who Gerbino also worked with on Factory Direct. He values connecting with other artists and meeting as many people as possible, but whether he’s exhibiting at the Carnegie or holing up in his studio, the daily practice of making art is what he always comes back to. “The most important thing is to trust in your work,” he said. “Your strength as an artist comes from your work. Nothing else.”

Contact Fabrizio Gerbino to visit his studio, or see his work in person at Industry of Art through August 24 at BWAC (Brooklyn Waterfront Artists Coalition).

Leave a comment