by Zach Hunley

All photography by Chris Uhren

Pittsburgh is, as I’m told by those who have resided here for longer than myself, a city of trial and error, a place of rebirth and renewal, and a site of change and fluidity. In the now over two years since I began to call this place my home, galleries have risen in the unlikeliest of places — Tomayko Foundation occupies a former dental office, april april resides in a space previously operating as a flower shop. Romance now joins these ranks, shifting from the living area of owner/director Margaret Kross’s apartment in Shadyside to a former cardiologist’s office in North Oakland. The current exhibition, Fourth River, on view through August 17, assembles the work of 16 artists and culminates in one of the most phenomenologically affective exhibitions I’ve witnessed — not just in the city of Pittsburgh, but anywhere. Kross could not have orchestrated a better “first show” in this new space.

The exhibition’s title references the network of underground aquifers and tributaries which flow under and towards the central portion of Pittsburgh, coalescing at the Point — an unseen “Fourth River.” Pulling from the conceptual through lines and metaphoric possibilities of this folkloric mythos, the work engages with regional themes of identity (both within and beyond the city, and even the country) and meaning making as they exist below the surface. A spirit of interrogation unites the show, revealing what had not been seen but always was. What’s concealed is nonetheless deeply felt and materially present.

You enter into the space via a ramped breezeway, adorned with industrial low-pile carpeting and plasticky plaques offering the names of medical practitioners and white collar professional offices still on site. The current entryway for the gallery features grey floor to ceiling cabinets, onto which hangs Sophia DiRenna’s graphite on paper drawing Walking, Running, Sitting (2024). The feathery pencil work depicts a kinetic and interlaced collage of loving, longing, and leaving. You feel pulled into the space in a way that piques curiosity — am I entering a gallery, or some uncanny, forgotten backrooms? What happens when those disparate sensibilities become one?

Hooking around and to the right you are greeted by a portal previously used to check in patients, offering a framed view into one of the central gallery spaces. For now, remnants of the former office are still present — the yellowy beige monitors of mid-80s computers still rest on the desks. In this space is work by Finn Dugan — may (2025), a delicate, rhythmic, and tendrilous sculpture which couples organic and industrial materials. Alice Gong Xiaowen’s todo-shaped, stainless steel clad soapstone ornament – Clasp (2025; one of two in the exhibition) rests opposite to Dugan’s work, almost like a portal or beacon. Erin Jane Nelson’s Frenier (2018) is a sculptural assemblage depicting the titular southern Louisiana ghost town through a folk art aesthetic.

The most curious inclusion in this space is from the Pittsburgh modernist Robert Lepper, who passed away in 1991. His Untitled work from 1959 sits as a physical manifestation of the exhibition’s aim to navigate the entangled legacy of industrial modernism. That topic is especially weighty in its theoretical baggage, and has been discussed at length in academic circles since the mid-20th century.

It felt especially fresh to see this exhibition engage with the afterlives and aesthetics of modernism around a theme of place as a site for veiling and uncovering, of looking and overlooking.

The aesthetic landscape of Romance’s new space pulled me next towards the back hallway, which snakes around and branches off into pockets of gallery space — “Back Storage,” “Exam Room 2,” and “Exam Room 3.” Jono Coles’s photo series Office2 occupies the storage room and feels like a simulacrum of the space’s potential future had the gallery not moved in. These photos are windows into vacant corporate spaces which feel tenuously alive despite existing in a vacuumous pause. Aesthetically, these works recall Thomas Demand.

Max Guy’s No Reason is a major highlight. Occupying the third Exam Room, the video installation makes use of two-channel audio — two radios, one set to AM, the other FM — and video coverage Chicago’s annual St. Patrick’s Day festivities wherein the city dumps verdant dye into the city’s waterways. Guy uses this coloring as a green screen, shifting the dye black instead. The result is an absurd and wholly unique sensory experience; no two viewings will be alike. I felt humor abound, and also discomfort — I couldn’t look away.

Across the hall is an intriguing pair of work by Katherine Hubbard and Ido Radon. Hubbard’s photo, untitled (tread), uses scale and selective framing to connect the onslaught of “luxury” apartment developments in neighborhoods like East Liberty with destruction and upheaval; what we see appears as an armored tank captured with something like night vision technology. Radon’s sculpture is the artist’s take on Frank Lloyd Wright’s abandoned plans for the Point Park fountain — a now iconic fixture of the Pittsburgh skyline. Something about this piece feels deflated, un-spirited. Together, these works sing a song of toe-stepping and communal self-sabotage.

This end cap grapples with urban Modernism’s legacy and conceptually loops around to the most transformed wing of Romance’s new space — the “Main Gallery.” Work here emphasizes material and form along with expression and impact. While this new location as a whole will likely see continued aesthetic changes, this space feels the most elevated beyond its medical office past. Gone in this area is the corporate carpeting, now revealed is the sandy concrete that once lived underneath. There is a graceful and accidental poetic with this material, as three natural hairline cracks from years of settling have created an almost topographical surface mimicking that of the city.

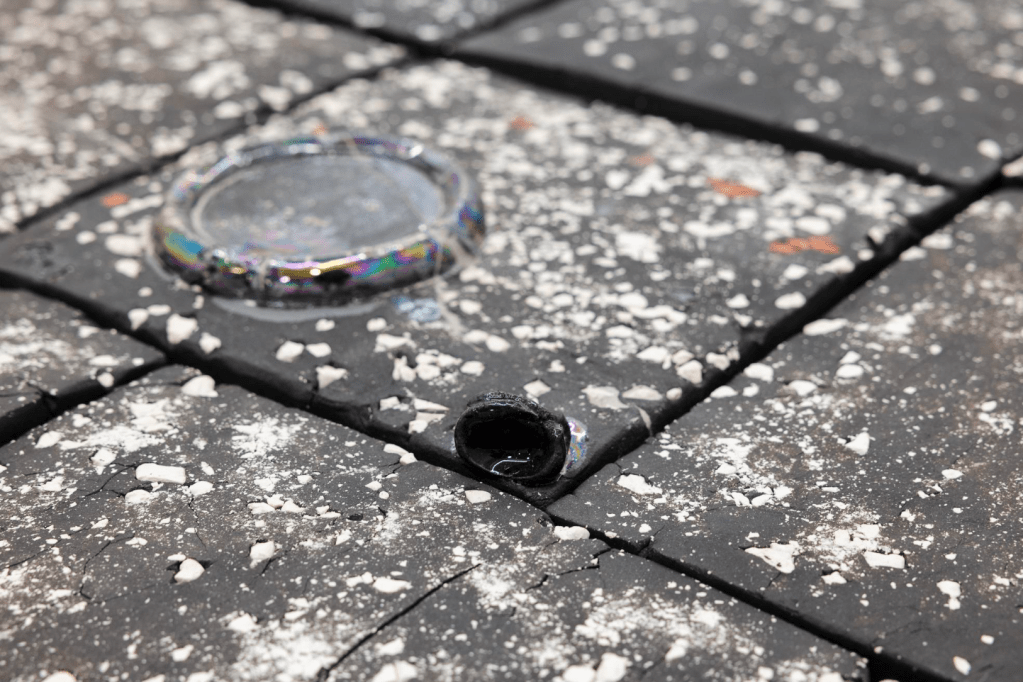

These tripartite lines etch their way across the floor — like the outlines of the Allegheny, Monongahela, and Ohio rivers — and converge under Kahlil Robert Irving’s Stella: bye BLUE:STARlight [{bells ring for freedom]. This square floor piece is elevated four inches off the ground and consists of an orderly array of glazed and unglazed ceramic tiles contrasted by chaotic shards of mixed media accoutrement. Neighboring along the floor is another work by Alice Gong Xiaowen, The lowly hallowed, a weighty work of cast iron that appears as a pool of cloth, or the surface of a running stream.

Stella: bye BLUE:STARlight [{bells ring for freedom]

The third work occupying off the wall space is Sophie Friedman-Pappas’s Kiln Building 4. Examined without the title, this work challenges visual understandings, materializing as a scale model of underground civil infrastructure — perhaps a means for carrying drainage runoff. Read in concert, these three sculptural works pull from the aesthetic lineages of post-minimalism while boldly declaring their conceptual independence by plainly revealing the external forces which shape their material realities. These are works which hide nothing.

On the periphery of the main gallery rests the work of Armanis Fuentes, whose academically trained mastery of the medium of fresco is a wonderfully delightful standout. Two Untitled brick shards produced during their residency at Bunker Projects earlier this year are included in the show and are based on snapshots taken during travels to Puerto Rico — their family’s country of origin. These petit works possess a refined, cinematic magnetism; be sure to spend some time peering into these tiny windows.

In viewing this exhibition with Kross, it became clear that a central tenet of this show’s conceptualism is the idea that generative creation is often born from collective grief and failure. Rather than grappling with the inhospitable aspects to Pittsburgh’s urban landscape from one of the most sought after neighborhoods in the city, Romance is now at home amongst one the city’s more overlooked yet bustling business districts. This move proves Pittsburgh’s boundless capacity as a site for transformative creativity.

As my colleague Pria Dahiya noted in the first piece of coverage on the Tomayko Foundation to be published on Petrichor last year: “Liberty Avenue is not where I go when I need a breath of fresh air.” I would certainly say the same about North Craig St.; the area is certainly a change from the quaint, tree-lined blocks of the gallery’s former home. The brightest colors in the immediate vicinity come from the awning of the neighboring Sunoco station. Nevertheless, Kross has struck genius with this exhibition and new location, and I am eager to see Romance continue to enter and settle into this new era. Fourth River is not to be missed; congratulations to everyone involved!

—

Fourth River is on view at Romance, 155 N. Craig Street, Suite 110, through August 17, 2025. Gallery hours are Fridays and Sundays from 12-6pm and by appointment. Visit romance-gal.com for more information on the exhibition.

J. Zach Hunley (they/he) is a Pittsburgh-based modern and contemporary art historian, critic, administrative professional, photographer, collector of things, and proud father to a senior guinea pig. With a keen observational eye, they use their writing as a means to refract their deep appreciation for formal aesthetics through a socially engaged lens. They hold an M.A. in Art History from West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, and docent for the Troy Hill Art Houses.

Leave a comment