by Shawn C. Simmons

All images courtesy of the artists and Chris Uhren

Accounts of mysticism, from sacred texts to contemporary scholarship, tend to frame such encounters as solitary: moments of revelation, rapture, or quiet attunement in which the self dissolves into something vast and ineffable. Yet in I Believe I Know, the Tomayko Foundation’s latest group exhibition, that intimate singularity is refracted through four distinct artistic practices, each wrestling with the question: What does it mean to feel connected to something bigger than myself? The show’s title, like the experiences it stages, straddles conviction and uncertainty.

Curator Nina Friedman recounts that she hadn’t set out to gather “mystical” works. The through-line emerged naturally over the course of studio visits, when questions of the divine and the cosmic kept surfacing. Curatorially, it’s a rare case where the theme announced itself rather than being imposed. It also suggests an ambient desire among these artists—one that moves fluidly between the languages of religion, science, and personal ritual—to locate meaning within a fractured cultural landscape.

The curatorial text invokes the psychologist and philosopher William James, who wrote in The Varieties of Religious Experience (1902) that in mystical states “we both become one with the Absolute and we become aware of our oneness.” I Believe I Know seizes on this paradox: the ineffable singularity of spiritual experience and its translation into forms we can collectively witness. The exhibition becomes, in Friedman’s words, a “crucible” for moments drawn from nature, religion, the solar system, and language, each a site where the human brushes against the divine.

We begin with Centa Schumacher’s photographic prints, which convey the show’s dual investment in empirical observation and metaphysical speculation. Schumacher is recognizable for her lens-based experiments with scale and light, Schumacher extends these concerns in a new direction, producing quiet black-and-white landscapes and interiors overlaid with pale, otherworldly rings, artifacts of a double exposure process. Because the second exposure is not mapped precisely onto the first, the rings drift unpredictably across the composition, their placement determined as much by chance as by intention. Each abstraction floats across the images like halos, portals, or celestial bodies just beyond reach.

Schumacher’s inspiration came, of all places, from a 2022 issue of Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. The article “A Giant Arc on the Sky” (Lopez, Clowes, and Williger) describes an enormous astronomical structure, an arc of galaxies so large that its very existence challenges cosmological models. We might understand this as an invitation to inhabit a visual field where human perception meets the unfathomable. The rings, drifting without pattern, become persistent companions, following the artist throughout her time on this planet, as she puts it. In this sense, the work demonstrates a cosmographic impulse: to map the movement of images across time and space as a way of charting our psychic relation to the infinite.

Where Schumacher turns her gaze skyward, Sobia Ahmad works in the opposite direction, literally rooting her practice in the earth. The Breath within the Breath (2024) centers on Pando, the aspen forest in Utah that is, by some measures, the largest living organism on Earth, connected by an immense subterranean root system. Ahmad spent time there for her MFA thesis project, filming and photographing this living network. For I Believe I Know, she presents a continuous, panoramic photograph of the forest. The image is shot in 360 degrees and installed on a low, continuous bench of her own making, stretching diagonally across the gallery and complete with cushions for viewers to enter the image’s quiet expanse.

Ahmad draws on spiritual ecology and Sufi traditions, where the theme of oneness is both theological and experiential. In Sufism, the distance between self and cosmos collapses; Ahmad’s panoramic bench does something similar in spatial terms. By compressing the forest into an unbroken image, she allows us to see the vast organism in a single sweep, even as the installation insists on slow, embodied looking.

Ahmad’s installation offers a vision of interconnectedness that resists full transparency. We can see Pando’s trunks, leaves, and light, but never the hidden root system that makes it one. Ahmad’s work carries the spirit of Suzanne Césaire’s writings in which Césaire insists that the natural world is not inert backdrop but a living, thinking presence—cosmic, breathing, speaking—that shapes human consciousness. In Ahmad’s work, the divine is not abstracted from the environment, but embedded in the patient, entangled life of the forest.

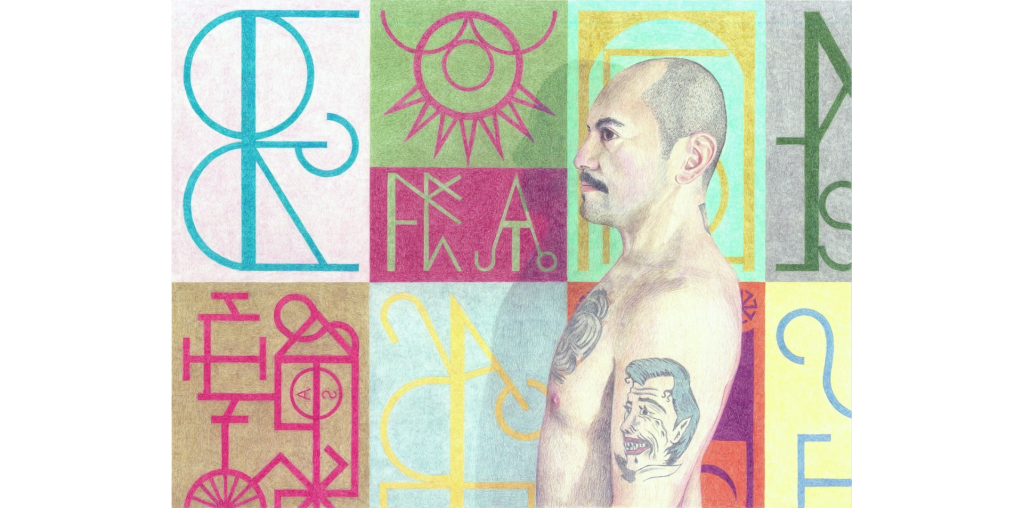

If Schumacher and Ahmad invite us to lose ourselves in cosmic and ecological immensities, Elijah Burgher’s drawings insist on the privacy (and even the opacity) of mysticism. Working in colored pen on paper, Burgher creates sigils, symbols derived from spells, compressed into abstract forms only fully legible to the artist. At first glance, the works read as a hybrid of geometric abstraction and asemic writing, with lines knotting and folding back on themselves. But each is a condensation of language, desire, and intention, operating within the tradition of ritual magick.

In the tradition of queer abstraction, a strand of contemporary art in which formal abstraction carries coded references to queerness, such opacity is not a failure of communication but a refusal of dominant legibility. As scholars like David J. Getsy and Lex Morgan Lancaster have argued, queer abstraction operates in the space between visibility and secrecy, using form to register experience without rendering it transparent to all viewers. They also confront James’s paradox of oneness from the opposite direction: the divine here is not universally accessible but deliberately withheld. The viewer stands at the threshold of a closed circuit, aware of the charge but unable to fully decode it.

Maggie Bjorklund’s paintings operate at the intersection of the earthly and the sacred. Her process of manipulating thin layers of oil paint with scratchy, sweeping brushstroke produces mutable forms that hover between recognition and dissolution. Decomposing material (it is plant matter? Flesh?) seems to emerge and recede in the same stroke. In Assumption of the Virgin (After Titian) (2024), she distills the bombast of the Renaissance original into a looser, more elusive gesture, stripping away narrative clarity but retaining a sense of upward pull.

Bjorklund’s attraction to both decay and transcendence suggests that the sacred often appears in the profane, the holy in the most ordinary materials. Her paintings propose that revelation may reside not in the monumental but in the ephemeral details of living matter. There is an intimacy here: a sense that the sacred is always on the verge of slipping from view, as subject to entropy as anything else.

What’s striking about I Believe I Know is how well it balances divergent approaches without collapsing them into sameness. Schumacher and Burgher approach the mystical through forms of language visual or symbolic that demand translation; Ahmad and Bjorklund work more directly with materials and environments that enfold the viewer. The exhibition moves between scientific cosmology, ecological oneness, and occult ritual without privileging one mode over another.

In a group show, “singularity” risks becoming metaphor rather than experience. And yet here, the collective presentation strengthens the paradox: singularity as both personal and shared. James’s mystical oneness becomes, in this context, less about merging into a single, universal experience than about recognizing the irreducible particularities of each encounter.

That the show’s theme emerged organically is perhaps its most telling feature. These artists’ return to unprompted questions of transcendence suggests less a retreat from the world than a reorientation toward the points where personal ritual and cosmic scale overlap.

The singer-songwriter Samia, in a lyric that could almost serve as wall text here, writes: “Did you know Aspen Grove is forty thousand trees with the same foundation? Some people see a cobweb hanging in the window, but you see a constellation.” Ahmad’s two contributions offer precisely these paired images: the vast, unseen root system of the Pando grove and the fragile geometry of a spider’s web. Together, they hold the paradox at the heart of I Believe I Know: that singularity is never simply solitary, but is sustained by networks and invisible bonds. The grove’s forty thousand trunks share a single foundation while the web’s glistening threads map out a cosmos in miniature. Whether we name this relation mystical, ecological, or cosmic, it is both one and many. A constellation of singularities.

I Believe I Know is on view at the Tomayko Foundation through September 19. Hours are 11am – 4pm Monday – Friday, and weekends by appointment.

Shawn C. Simmons (he/him) is a Pittsburgh-based art historian, educator, and writer.

Leave a comment