Reflections on Black Photojournalism at the Carnegie Museum of Art by Tara Fay Coleman

Walking into Black Photojournalism at the Carnegie Museum of Art feels less like entering an art exhibition and more like stepping into the living memory. Co-organized by Dan Leers, the museum’s curator of photography, and Charlene Foggie-Barnett, community archivist for the Charles “Teenie” Harris Archive and a longtime Hill District resident, the show draws from a wide national network of archives and collections to trace the work of Black photojournalists in newsrooms that had to fight to be seen from the end of World War II through the mid-1980s.

The museum’s wall text quotes the catalogue: “Photojournalism is work and it is livelihood. It is craft and it is documentation. It is a way to be in the world and to share the world. It is a way to resist oppression while insisting on the fullness of life.” That insistence is the through-line here. The images do not present history as something that merely happened to Black communities, they reveal it as something lived, recorded, argued over, and carried forward.

The exhibition gathers work by about 60 photographers. There are heavy hitters like Gordon Parks, whose assignments for Life magazine helped define the mid-century mainstream’s visual language, alongside Charles “Teenie” Harris, John H. White, Moneta Sleet Jr., Ernest Withers. These names are widely known in some cities, but often absent from the broader canon. There are many more whose contributions will be new to museum audiences. Their collective presence makes it clear that Black photojournalism was never a side note in the story of American media; it was a parallel, often oppositional, way of seeing.

The museum has called this show a “point of departure.” That claim is partially true – no other major U.S. museum has mounted a survey of this scale. Yet it is also incomplete. These histories were never lost. They were preserved by Black newspapers, families, local historical societies, and by archivists such as Foggie-Barnett long before the museum decided to center them. To call this the beginning is to use the museum’s timeline, rather than the photographers’ own.

The presence of Foggie-Barnett as co-organizer matters. The Carnegie Museum acquired the Harris Archive in 2001, but that acquisition was only the start of decades of work, much of it undertaken by Foggie-Barnett and other community members to identify, contextualize, and maintain a connection to the people and neighborhoods they depict.

That a Black woman from the Hill District, a community that produced both Harris and the Pittsburgh Courier, helped shape this exhibition brings a needed layer of accountability. Yet the institutional frame persists. The catalogue repeatedly describes the museum as “creating space” for this history. That phrasing risks presenting the museum as the generous host, rather than the latecomer to a story Black communities have long sustained. The exhibition benefits from the collaboration, but the question remains: does the museum see itself as a steward of a living tradition or as an arbiter of its historical value?

Artist David Hartt designed the galleries with a careful sense of space that resists the blank neutrality of the white cube. Yet the museum setting inevitably slows the pictures down. These photographs were made for newsprint deadlines and public circulation. They were meant to be passed around, read quickly, debated. In the gallery, behind glass or in a frame, they risk becoming relics of their own urgency. The catalogue rightly calls photojournalism “work and livelihood,” yet in the museum the labor of photographers, printers, editors, and community distributors is mostly backgrounded. The exhibition makes a powerful case for these photographers’ artistry and perspective, but in doing so it sometimes detaches the images from the political and economic circumstances in which they were made.

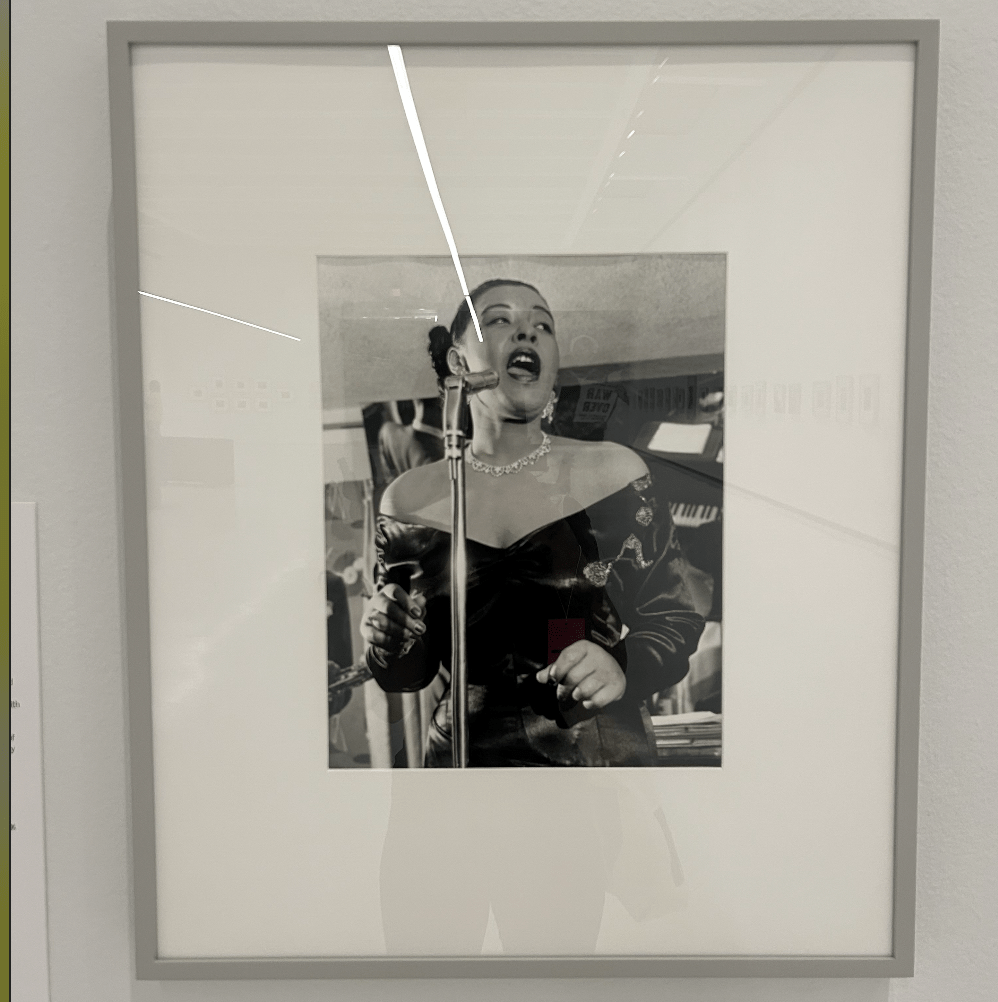

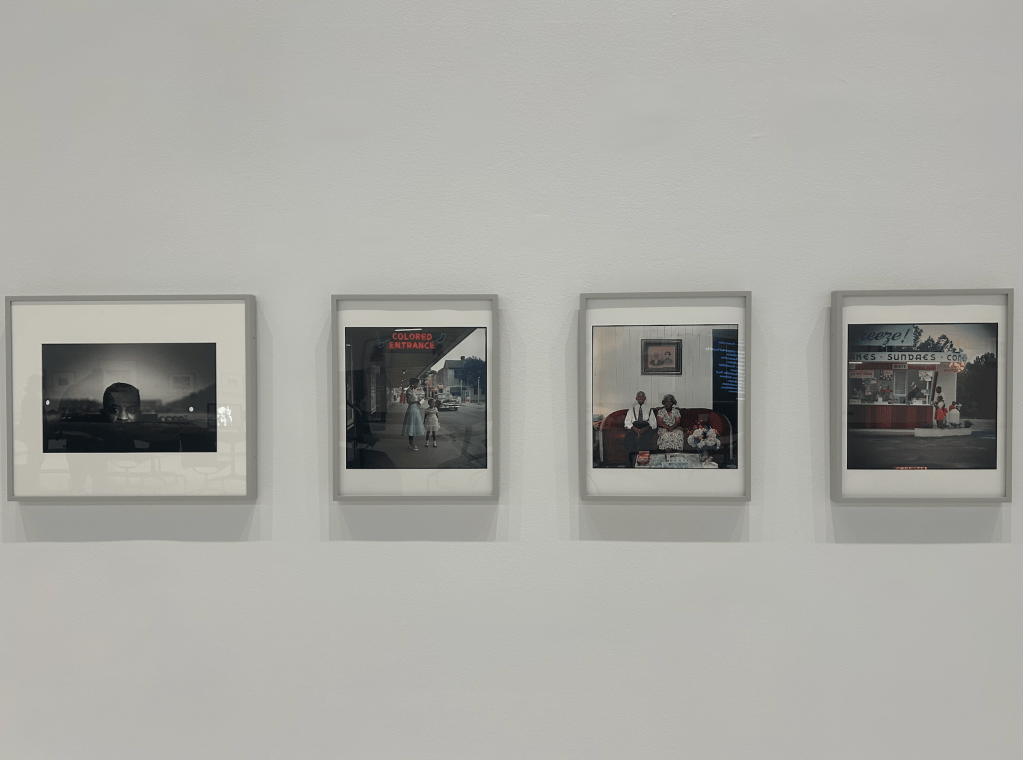

To its credit, the museum made a number of strong curatorial choices in the selection of many of the featured photographs, often opting for images that reveal the complexities of both the public events and the private realities of that period. As I moved through the galleries, a handful of images stood out to me, and have stayed with me since, particularly Gordon Parks street scenes and portraits, precise in their composition, yet unsparing in what they reveal about their subjects and their circumstances; the historical depth of Ernest C. Withers; the restrained intimacy of a portrait of Billie Holiday by Bob Douglas; Robert A. Sengstacke’s images of the men and women of Islam whose composure reflects a collective discipline rarely represented in mainstream media of that era. These works, dispersed across the exhibition rather than grouped together, showed a clarity and directness in the way that they registered both historic change and everyday life.

The exhibition makes a powerful case for these photographers’ artistry and perspective, but in doing so it sometimes detaches the images from the economic and political struggles of the Black press that gave them life. The chosen time frame, 1945–1984, links the rise of postwar Black-owned media with the height of civil-rights struggles and ends in the early Reagan years. The frame is defensible, but it can feel too clean. The battles over representation, and the strategies Black photographers developed to meet them, did not end in 1984. That cutoff invites a future show that could potentially connect this lineage to the ongoing fights over visual power in the age of cable news and social media.

Despite these tensions, Black Photojournalism does something crucial by foregrounding the collective labor behind each image. Early in the show, a Charles “Teenie” Harris photograph of a Pittsburgh Courier press operator reminds us that news photographs are the product of entire networks that include reporters, editors, printers, couriers, activists, and readers. That recognition gives weight to the catalogue’s claim that “each picture represents the energy of many dedicated individuals who worked to get out the news every single day.”

press operator prints newspapers, 1954, Carnegie Museum of Art, Heinz Family Fund, 2001.35.3136 © Carnegie Museum of Art

The curators’ decision not to present the show as a strict chronology also matters. It allows for resonances across decades where a protest image from the 1960s can face a domestic portrait from the 1970s, prompting viewers to think of history not as a single arc but as overlapping layers. Black Photojournalism succeeds as both historical survey and provocation. It honors a lineage of photographers who worked in often-hostile conditions to make Black life visible, and it insists that their work shaped not only the record of that life but the broader visual culture of the United States. It is also worth arguing with. The exhibition asks what it means for a large, historically white-led museum to narrate a tradition that emerged in resistance to the mainstream institutions of its day. That friction between collaboration and institutional authority gives the exhibition its critical charge.

The catalogue’s opening line reminds us that photojournalism is a way of sharing the world as well as claiming the world, of deciding what counts as news and whose experiences deserve the dignity of record. That work did not end in 1984, and it does not end at the museum’s door, either.

Black Photojournalism runs through January 19.

Tara Fay Coleman is an artist, independent curator, writer, and cultural worker from Buffalo, NY. Her practice aims to explore how power, race, and history shape what is seen, and what is systematically obscured. Working across art, writing, and curation, she centers Black cultural production that resists dominant narratives, and reclaims the right to self-representation. Rooted in lived experience, her work aims to challenge institutions to confront their exclusions, while creating space for stories long marginalized. Her goal is to always curate with a commitment to presence, complexity, and care, and she envisions cultural spaces where artists are not only visible, but central, and where art fosters joy, connection, and self-determination. Tara Fay currently lives and works in between Pittsburgh, PA, and New Haven, CT.

This month’s articles are produced with support from the Frick Pittsburgh in conjunction with their landmark exhibition The Scandinavian Home: Landscape and Lore. Get cozy as the seasons change with David and Susan Warner’s collection of paintings, tapestries, and sculptures from around the Nordic region. Tickets now on sale.

Leave a comment