Exhibition Review by Zach Hunley

All photos courtesy of the artist

Homestead workers made beams for the Empire State Building. Their collective hand is embedded in the structures that millions encounter, unthinking, everyday… Visit Carnegie Hall or the Frick Museum in New York, and the amassed wealth they represent is the surplus labor of Homestead workers, whose union Andrew Carnegie and his plant manager Henry Clay Frick decided to break by armed force in 1892, aided by the state. Of the Homestead Works themselves, which had sprawled for four miles, almost nothing remains. A few brick smoke stacks, tower above a grassy slope near a shopping center and some parking lots.

— Quote provided by the artist; from Homestead Steel Mill: The Final Ten Years, by Mike Stout (2020).

—

How can art direct us to a new understanding of our fraught dependance on the natural world and our misplaced economic tethering to the blind extraction of its resources? Strewn from the complex matrix of friction, time, and place, the tides underpinning these quandaries coalesce in the artist Steve Rossi’s exhibition Liquid Resonance, at the Paul Mesaros Gallery at West Virginia University’s Canady Creative Arts Center. The currents of misuse, eroded histories, and buried truths in this exhibition, comprised of three distinct series, result in a powerful viewing experience that chisels away at the already crumbling facade of our present gilded age.

The Mesaros Gallery spaces present unique challenges for exhibiting artists — they are somewhat subterranean, with ramps descending into the primary space, lack external windows, and, specifically with the Paul Mesaros Gallery, feature dark, slate flooring with a primary wall made of monochromatic, textured stone. Rossi’s work feels uniquely suited to the space, making the most of what could otherwise be limitations. Though, in the case of this show, the work you see with your eyes is only part of the experience.

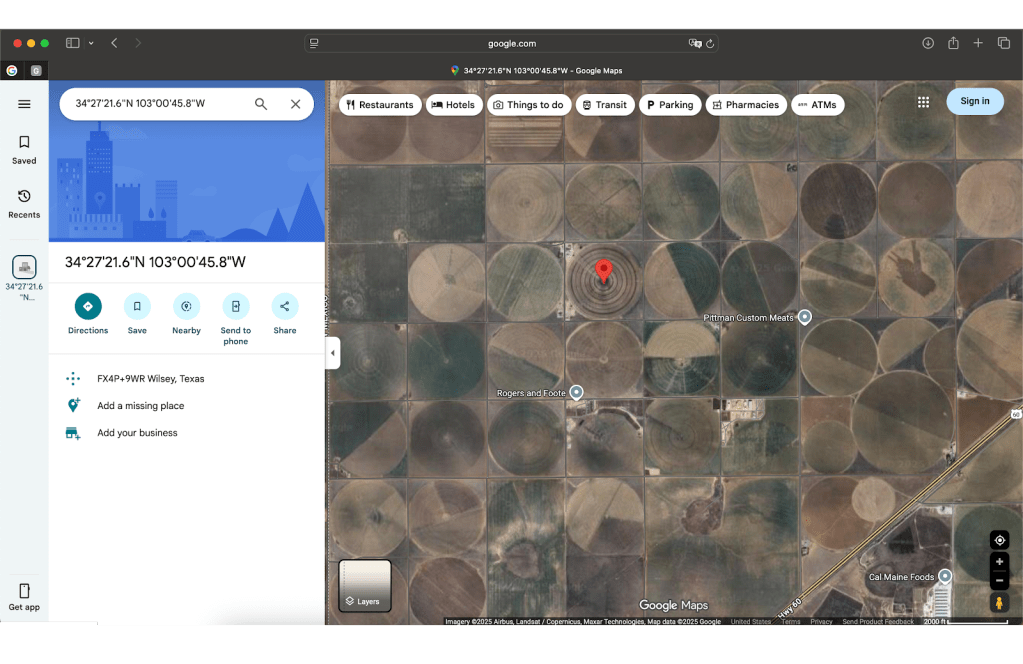

The show greets you not only visually, but aurally as well; the soundscape from the projected video installation, unseen until you descend into the gallery space, bathes your ears and mind with a groundswell of emotive tension. It’s best to start with this synthesized component of the exhibition, 34.455988,-103.012734, (video) and Beneath the Steam (sound by Robbie Wing (Cherokee Nation)). Rossi uses geographic coordinates to direct our attention to the source of inspiration for this body of work.

In conversation with the artist, he shared that, after his brother accepted a job in Clovis, New Mexico, Rossi began to observe the visual and topographical impact of groundwater irrigation across the vast expanse of the western landscape during his flights in and out of the region. For Rossi, these gridded, inlaid circular networks visually recall the work of mid-century Land Art movement artists, like Nancy Holt or Michael Heizer, as well as the practice of quilt making. However, upon further rumination on the material realities of industrial resource extraction, these observations quickly became political — as all landscape is. We may not have similar agricultural practices in Appalachia, but we certainly share a common sociopolitical history, be it with coal or steel.

The video component to this piece presents the enmeshed nature of water and humans, as we siphon the diminishing liquid resource towards ends calculated by those at the heads of multinational corporations often situated comfortably away from the communities their decisions impact. The video pulses, at an increasing rate, the visuals of the water’s surface with the circular irrigation patterns overlaid and interstitched. Wing’s audio signals this increasing suspense, quickly building from ambient meditation to a harsh, tensile churning. I was entranced.

The two multimedia paintings in this show, 34.233707,-103.084940 and 34.35553,-103.0077549 (both 2022), visually pull from the same theme of irrigation and maintain a bird’s-eye perspective. These works most squarely align with Rossi’s interest in the modernist visual aesthetics related to geometric abstraction. The efficacy of Rossi’s artistic practice lies at the crossroads of this interest (stemming from the legacy of the mid-century artists like Kenneth Noland, for example) and his desire to impart a certain degree of critical, socio-historical voice. At this unlikely intersection, Rossi has found the means to convey a view of the histories underpinning extractive resource and labor struggle.

Rossi’s paintings in this exhibition are, at a base level, landscapes; it’s the rendering of the land — a land that man has already rendered in this way — that calls into question what the viewer is seeing, and what it means. The tension in the work outside of the video installation, created in the space between representation and abstraction, is subtle but felt. The works are not didactic, yet they harness a clear intent that directs the viewer towards an open and introspective questioning of how histories are told or forgotten, if untold. How do we remember? What gets to be remembered?

History is a central theme of this exhibition. Rossi has generational ties to Pittsburgh, with his great-grandfather and grandfather both having careers in the region’s steel mills; the Monongahela River Valley is a fitting thematic link, tethering the artist’s familial history to the work in a way that is palpable, but not overly reliant. A pitfall of such emphasis is that it becomes easy to be too dependent on personal narrative, such to the extent that the work becomes excessively esoteric. Rossi navigates around this not only via abstraction, but by looking outside of the regional vicinity, to the American southwest.

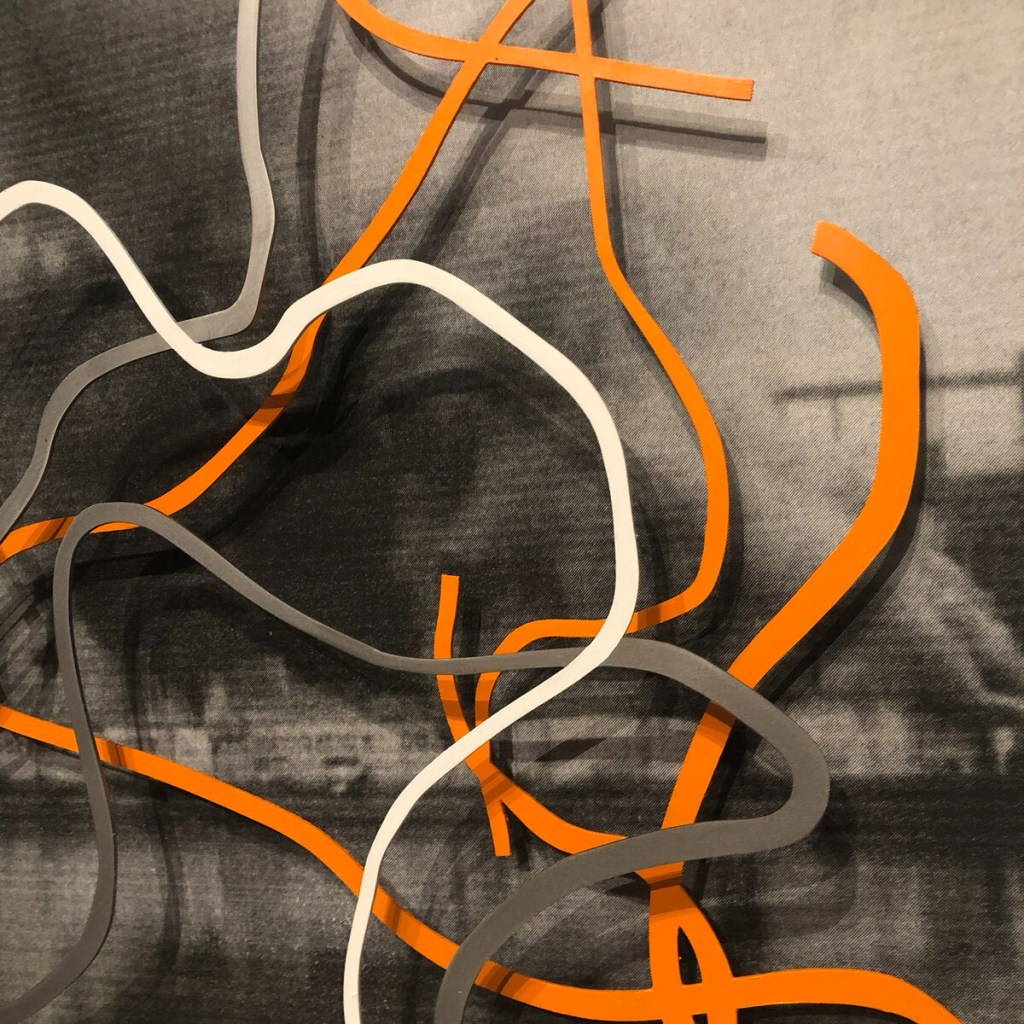

Having said that, the primary body of work in this show does center the Monongahela River Valley. Beginning in the region of Monongahela County in West Virginia, home to Morgantown, the river carves out its northward path until it reaches The Point in Pittsburgh, where it combines with the Allegheny River at the mouth of the Ohio. This 130-mile body of water is a central thematic anchor to the sculptural elements of Rossi’s exhibition, which collapse, reorient, and layer the meandering geographical outline of the river’s path to surprisingly varied and technically distinct artistic ends. This action literalizes the interwoven chapters of material history in our region, and serves to extend the river as a metaphorical connector across the body of work.

Five sculptural panels are included in this exhibition; The Battle of Homestead present the tendrilous form of the Mon River layered over historic photographs of the Homestead Strike of 1892 while the carved elements in the remaining works (collectively entitled Monongahela River in Six Parts, 2025) hover above a pale blue backdrop. The outline of the river in these works are made of waterjet cut steel, yet their presence in these works feels precarious and fallible. As you view these works in person, under gallery spotlighting, the river’s form casts a network of starkly contrasting shadows — our position as viewers becomes a an immaterial part of the work, revealing the living nature of history.

Fabricated from iron cast from 3D printed molds are the three sculptures on pedestals: Evolve/Revolve Monongahela River Valley No. 1, No. 2, and No. 3, as well as the monumental outdoor public installation Monument to the Monongahela (all 2025). The former three sculptures reveal themselves in relationship to one another as wedges taken from segments of the river’s path, with their physical depth and sense of warped perspective imparting the show’s central themes.

Monument… takes these notions of water, land, history, and place to new heights, with the path of the Mon River now soaring towards the sky. This piece visually relates to the structure of trees — organic organisms that, like humans, rely on water for their energy. Waterways such as the Mon River also constitute a type of siphon, collecting the drainage of the water table and allowing for the transportation of extracted resources upwards and out of its home region — a siphon of energy and materiality.

—

7 A.M. Monday

It’s a problem—a damn problem—whether to walk fast and get home quick, or walk slow and sort of rest. I try to go fast, and have the sense of lifting my legs, not with the muscles, but with something else. I shake my head to get it clearer. One bowl of oatmeal. Coffee. “I feel all right.” I get up and am conscious of walking home quietly and evenly, without any further worry about the difficulty of lifting my feet. “The long turns, they’re not so bad,” I say out loud, and stumble the same second on the stairs. I get up, angry, and with my feet stinging with pain. Old thought comes back: “Only seven to eight hours sleep. Bed. Quick.” I push into my room—the sun is all over my bed. Pull the curtain; shut out a little. Take off my shoes. It’s hard work trying to be careful about it, and it’s darn painful when I’m not careful. Sit on the bed, lift up my feet. Feel burning all over; wonder if I’ll ever sleep. Sleep.

— Quote provided by the artist; from Ch. V, Working the Twenty-Four-Hour Shift, in Steel, the Diary of a Steelworker, by Charles Rumford Walker, 1922

—

Steve Rossi’s Liquid Resonance was on view at West Virginia University’s Paul Mesaros Gallery through November 7th. On October 23rd, 2025, Rossi delivered an artist talk at WVU; a recording of the talk can be accessed here.

—

P.S.

I have always maintained that, as an institution based in the otherwise unassuming Mountain State town of Morgantown, the West Virginia University School of Art and Design regularly punches above its weight — having brought in the work of heavy hitters like Faith Ringgold, Marie Watt, Robert Rauschenberg, Shepard Fairey, and Peter Saul, among many others. The modestly sized Art Museum of WVU has over 4,000 pieces of art in its collection. I am no doubt biased, I attended WVU from 2017-2023, but the art on its campus unquestionably changed my life — it showed me what art could be and melded my way of seeing. Steve Rossi’s exhibition continues to demonstrate the institution’s capacity for transformational experiences in the visual arts. I recommend an arts day trip to anyone based in Pittsburgh — to see his show, the exhibitions at the Art Museum of WVU, and all that the Morgantown area has to offer. – ZH

—

J. Zach Hunley (they/he) is a Pittsburgh-based modern and contemporary art historian, critic, administrative professional, photographer, collector of things, and proud father to a senior guinea pig. With a keen observational eye, they use their writing as a means to refract their deep appreciation for formal aesthetics through a socially engaged lens. They hold an M.A. in Art History from West Virginia University, Morgantown, WV, and docent for the Troy Hill Art Houses.

This month’s articles are produced with support from the Frick Pittsburgh in conjunction with their landmark exhibition The Scandinavian Home: Landscape and Lore. Get cozy as the seasons change with David and Susan Warner’s collection of paintings, tapestries, and sculptures from around the Nordic region. Tickets now on sale.

Leave a comment