by Tara Fay Coleman

Performance is often misunderstood as spectacle. When people talk about performance art, they tend to reach immediately for extremes: endurance, shock, confrontation, bodies pushed to visible limits. The reference point is the familiar and predictable Marina Abramović. Suffering that reads clearly, work that photographs well and circulates easily. What that shorthand flattens is a wide field of performance that is quiet, durational, materially modest, and rigorous in ways that do not announce themselves. In Pittsburgh, this kind of performance is often met with resistance. Not necessarily hostility, but confusion, dismissal, or misunderstanding. The question I hear most often is not what the work is doing, but why it is happening at all. That distinction matters because it reveals how deeply spectacle still structures expectations of performance, and how quickly subtle labor is mistaken for insignificance.

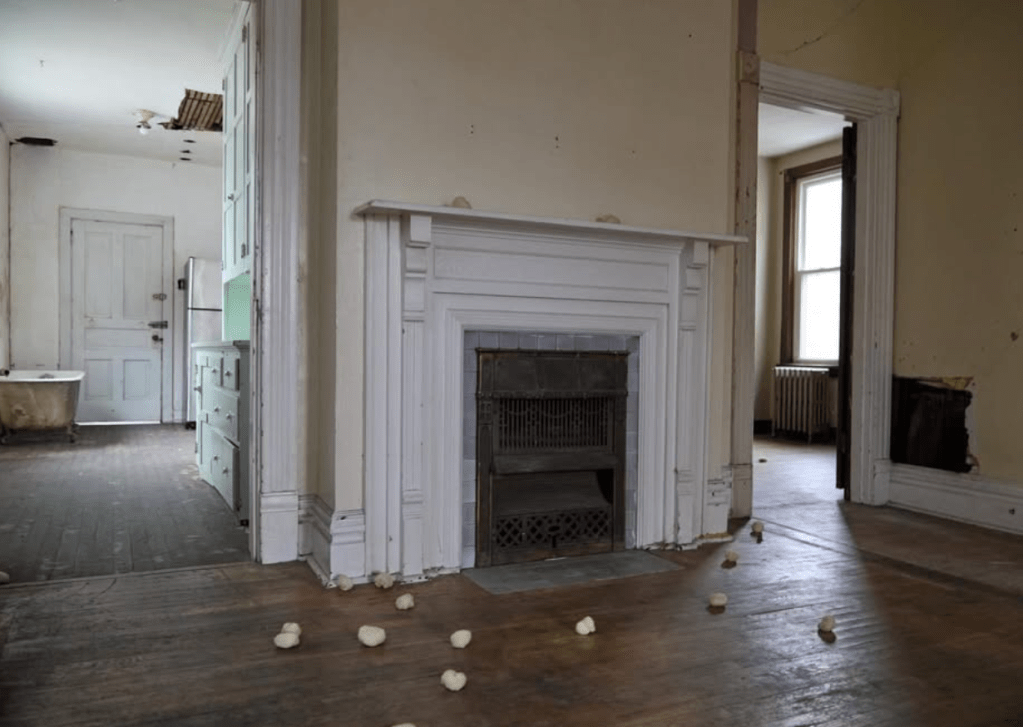

A recent performance by artist Cole Modell titled “*Sticky Rice with Zero Spatial Awareness” at (____), the experimental art space at 843 Holland Ave, centered on the live manipulation of sticky rice makes this tension visible. Over the course of about twenty minutes, the artist rolled and tossed rice spheres across the floor, remaining mostly in one position, occasionally shifting his body to redistribute coverage in the space. To an unprepared viewer, the action may have appeared minimal, even arbitrary. People asked how he found the space, as if surprised that anyone would permit something so apparently minor, even silly, to occur there. Without reading the accompanying text, many viewers had little sense of what they were witnessing.

Internally, however, the experience was far from passive. As the performance progressed, the gluten in the rice tightened, making the material increasingly difficult to manipulate. His forearms began to ache. The repetition produced real physical strain. The presence of the audience imposed its own constraint. Decisions had to be made quickly, without deliberation. Once released, the rice behaved unpredictably, sticking to itself, clinging to surfaces, producing a muffled tumbling sound as it rolled. The artist described the rice as having a mind of its own. What unfolded was not a presentation, but a negotiation between body, material, time, and space.

This gap between what is visible and what is experienced internally sits at the center of performance art, but it is rarely granted interpretive weight. When audiences encounter subtle performance without a familiar framework, attention often collapses, and confusion replaces curiosity. The work is reduced to what can be immediately seen, rather than what is being sustained. Performance breaks down not because nothing is happening, but because viewers have not been asked, by institutions or by repetition, to stay with it.

In my experience, this dynamic is not new in Pittsburgh. For years, I’ve done performance within a city that supports experimentation while simultaneously struggling to read it. Spaces like Bunker Projects have long operated as places where performance is not treated as an anomaly, but as a legitimate form of inquiry. As a residency and exhibition space, Bunker has supported work that unfolds over time, resists polish, and focuses on process over result. It has functioned as a performance space whether or not that was always named explicitly.

At the same time, the infrastructure that once helped build shared literacy around performance has thinned. Pittsburgh previously hosted the Pittsburgh Performance Art Festival, a recurring event that foregrounded live, site-responsive work and cultivated audiences willing to engage with performance on its own terms. Festivals like this did more than present work, they trained attention. Their absence leaves a gap, not just in programming, but in the shared language audiences use to approach performance now.

Within this context, I feel that outside of movement-based work, much contemporary performance in Pittsburgh continues to be met with resistance. I have encountered this response repeatedly, sometimes in overt ways, sometimes in passing comments that reveal more than they intend. During one piece, I read quietly in a room at an exhibition opening, positioning the act as part of the work rather than an add-on or interruption. While I was reading, I could hear people nearby whispering variations of the same question: how is that art? The comment was not hostile. It was casual, almost reflexive. And that is precisely the point. The resistance was not to the content, but to the form. Reading did not register as action. Presence did not register as labor.

The performance was happening in real time, but because it did not perform effort in a recognizable way, it was dismissed as insufficient. The work was not failing to communicate, it was refusing to announce itself. Other works have been received similarly. In The 8 White Identities, and You! (2024), I assumed the role of a secretarial figure in an office-like setting, tasked with surveying participants. The performance relied on stillness and repetition, and on the careful management of tone. By adopting a subservient and unassuming persona, I created a sense of ease that encouraged people to speak openly, often more openly than they realized.

Yet the work was often read as didactic rather than as a live examination of how whiteness is disclosed, measured, and performed in everyday interactions. I found that people simply did not understand how this was a performance at all. What was missed was the labor of holding that space, managing tone, and absorbing what people were willing to say once they felt safe enough to speak.

These responses echo what “*Sticky Rice with Zero Spatial Awareness” makes clear. Performance labor is frequently invisible to those who expect immediacy. Physical strain, internal regulation, and decisionmaking under observation,are not always legible, but they are the substance of the work. Performance does not always declare itself. Sometimes it mutters, repeats, or asks viewers to notice sound, texture, fatigue, or restraint.

The smallness of the Pittsburgh art scene cuts both ways. Its intimacy allows artists to navigate spaces more easily and to take risks that might be foreclosed elsewhere. But it also magnifies expectations. In a city where visibility is limited and legibility is prized, work that does not immediately explain itself risks being dismissed as insufficient. Subtlety is confused for emptiness, and quiet is mistaken for a lack of rigor.

Performance art does not require viewers to understand it. It requires them to stay, and to accept that meaning may not arrive all at once, or at all. Pittsburgh has supported performance before, and it continues to do so in pockets, through artists and spaces that insist on working this way anyway. The question is not whether performance belongs here, but whether we are willing to meet it on its own terms again.

Tara Fay Coleman is an artist, independent curator, writer, and cultural worker from Buffalo, NY. Her practice aims to explore how power, race, and history shape what is seen, and what is systematically obscured. Working across art, writing, and curation, she centers Black cultural production that resists dominant narratives, and reclaims the right to self-representation. Rooted in lived experience, her work aims to challenge institutions to confront their exclusions, while creating space for stories long marginalized. Her goal is to always curate with a commitment to presence, complexity, and care, and she envisions cultural spaces where artists are not only visible, but central, and where art fosters joy, connection, and self-determination. Tara Fay currently lives and works in between Pittsburgh, PA, and New Haven, CT.

This month’s articles are produced with support from the Frick Pittsburgh in conjunction with their landmark exhibition The Scandinavian Home: Landscape and Lore, running through January 19. Get cozy as the seasons change with David and Susan Warner’s collection of paintings, tapestries, and sculptures from around the Nordic region. Tickets now on sale.

Leave a comment