by Tara Fay Coleman

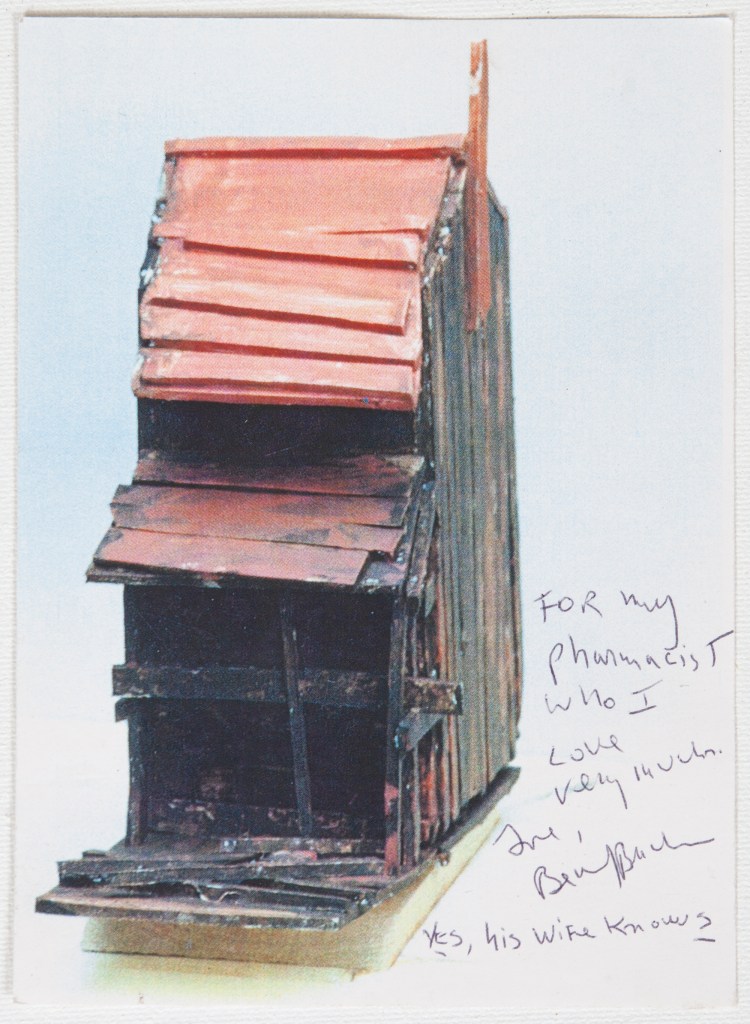

Cover image: Beverly Buchanan, Untitled, Undated [circa 1990s]. Color photograph. 4 x 6 in. Courtesy of Prudence Lopp.

I first encountered Beverly Buchanan while researching how I might make art that could allow me to process my parents’ deaths, which were both shaped, and ultimately hastened by failures in the medical system. Dominant art history frameworks would consider Buchanan’s work through the language of memory and vernacular architecture, but to stop there feels insufficient. What her practice records is the reality of survival under systems that were never designed to sustain Black life, Black disability, or Black longevity.

Looking at it now, amid renewed and ongoing threats to Medicaid and other public support systems, it becomes impossible not to read her shacks, drawings, and ephemera as forms shaped by structural neglect as much as by personal history. Buchanan did not arrive at art through ease or abstraction. Before committing fully to her practice, she trained in medical technology and public health and worked within those systems as a technician and educator. That background matters because it situates her work in an intimate understanding of how care is administered, and in many cases rationed and withdrawn. Her art does not speculate about vulnerability because it is made by someone who understood from lived experience how bodies move through institutions and what happens when support becomes conditional.

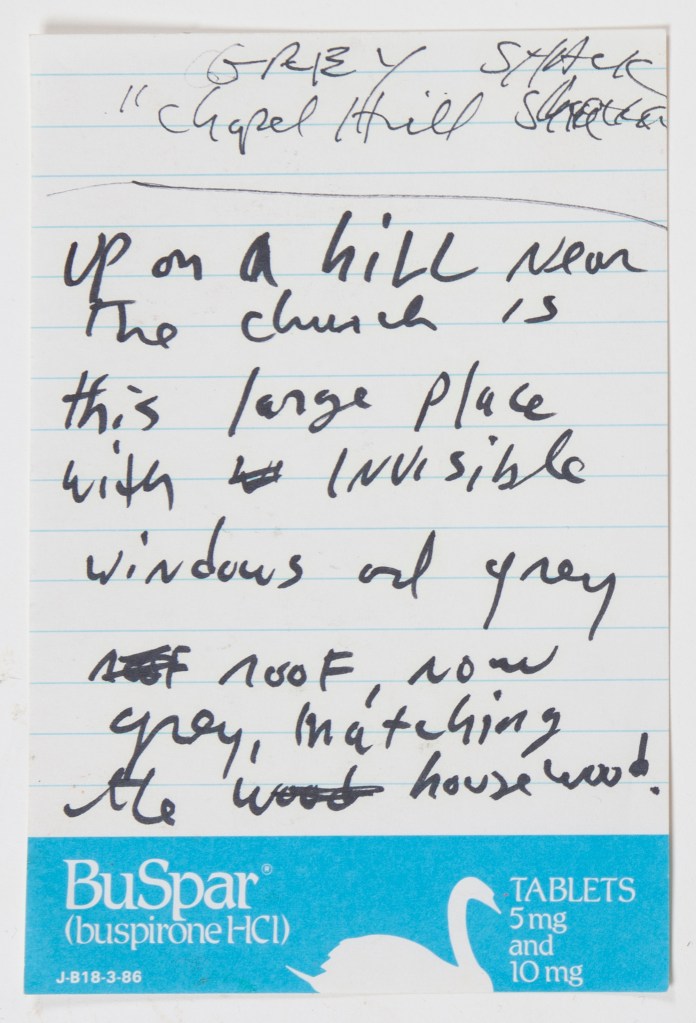

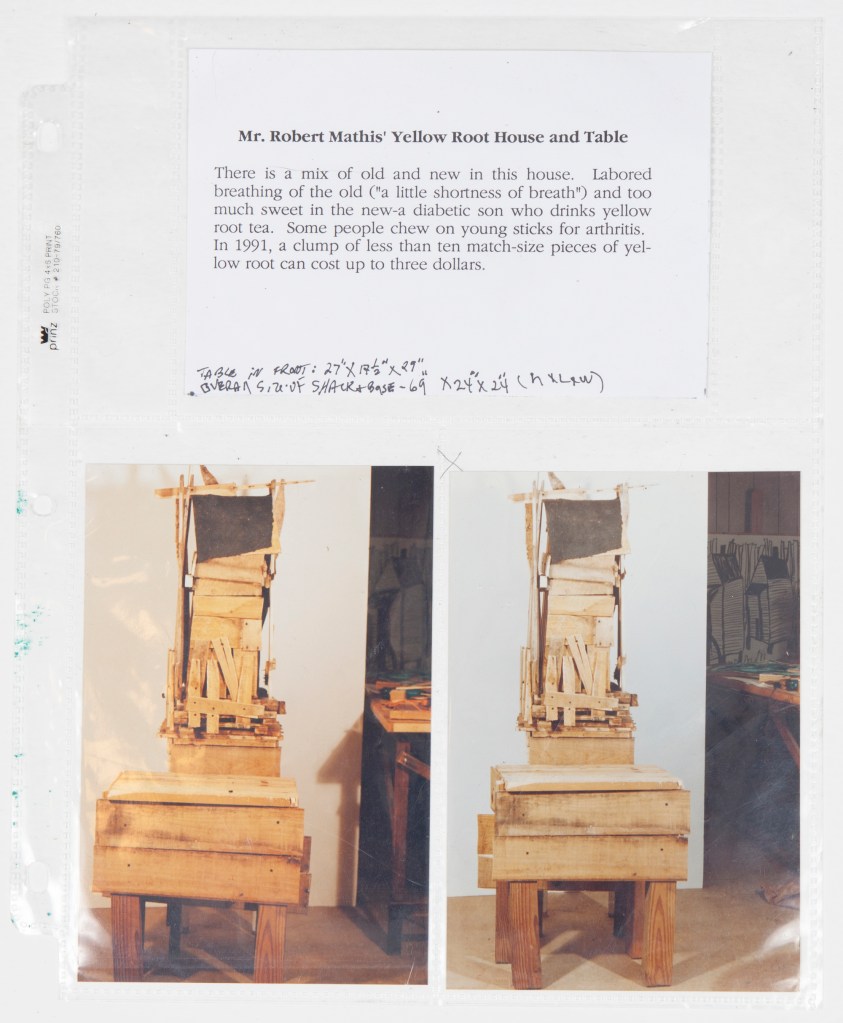

The exhibition Beverly’s Athens, on view at the Athenaeum at the University of Georgia, foregrounds the more than two decades Buchanan lived and worked in the city she considered home. Rather than centering her most recognizable works in isolation, the exhibition draws attention to the materials that accumulated alongside daily life. Small sculptures, photographs, drawings, printed matter, notes, and personal ephemera appear in close proximity, emphasizing how her practice unfolded through routine and dependence.

The exhibition reads less as a retrospective than as a portrait of a life shaped by sustained negotiation with place and care. Works are shown alongside references to pharmacies, medical offices, repair shops, and local businesses she relied on, which collapses the distance between artistic production and the systems that enabled her to function. In doing so, the exhibition insists that care, access, and mobility were not secondary concerns, but structuring conditions of her practice.

A similar logic shapes the pairing of her photographs with still-standing photographs of shotgun houses and archives related to the history of Linnentown, a Black neighborhood displaced by the University of Georgia., This pairing sharpens her long-standing attention to erasure and preservation, not as abstract concerns but as lived consequences of institutional power. The exhibition does not present Buchanan as an outside observer of these forces, she is positioned within them.

Buchanan lived for much of her life with chronic illness. That fact is not incidental to her practice, it’s foundational. Her work emerges from a life organized around medical appointments, pharmacies, medication schedules, and the fragile logistics of care. In this context, Medicaid is not a theoretical policy debate, it is infrastructure and time. It is the difference between continuity and interruption, between making work and not making it at all. When funding for public healthcare is threatened, it is not only bodies that are placed at risk, but the entire cultural ecosystems those bodies shape.

After leaving public health work and turning fully toward art in the late 1970s, Buchanan built a practice that unfolded across Georgia, eventually settling in Athens for more than two decades. This was the longest sustained period of her working life, yet it has rarely been centered. Athens was not a retreat or a late-career slowing, it was a site where she calibrated her practice to constraint. Her home functioned as a studio, archive, and care environment. Making work there was a necessity shaped by access and mobility.

What’s most striking to me is how Buchanan refused separation between daily life and artistic labor. Small-scale objects, handwritten notes, prints, and gifts circulated through informal networks rather than institutional channels. These exchanges were not minor. They formed an economy rooted in mutual reliance. When public systems fail, communities invent their own ways of bartering. Buchanan’s work documents that invention without romanticizing it.

Equally important is the attention given to her home environments. Large-scale photographs, studio documentation, and images of her garden foreground the boundary between domestic life, disability, and artistic labor. These spaces are shown not as retreats, but as working environments shaped by constraint. The garden, in particular, reads as a site where care and endurance converge. Gardening requires repetition and faith in slow returns. It is care practiced without guarantee. In a society that routinely withholds care from the most vulnerable, the cultivation of abundance is almost an insistence on continuation. Buchanan’s gardens are not necessarily decorative, they are assertions of life sustained despite neglect.

It is important to note that Buchanan received national recognition during these years. However, fellowships and institutional visibility did not translate into security, and recognition did not remove her from precarity or dependence on informal care networks. Her career makes this clear: visibility does not equal protection. Reading her work against contemporary healthcare cuts illustrates that these policies do not simply reduce services, they restructure who is allowed to endure. Buchanan’s archive shows what is lost when care is withdrawn.

Not only lives, but histories and ways of seeing disappear alongside it. Buchanan never separated disability from creativity or care from art making. She understood that the conditions under which one lives shape the forms one produces. Her practice stands as a reminder that cultural production does not float above material reality; it is embedded within it. To engage her work seriously now is to confront the systems that made her life precarious and to recognize how many artists continue to work under similar conditions.

What Buchanan offers is not a lesson in resilience. It is a record of persistence shaped by knowledge, by labor, and by care. Her work does not resolve structural abandonment, but it forces us to acknowledge it during a time where we cannot afford not to.

Considering this exhibition from the perspective of someone who spent most of her life living in Pittsburgh, it feels unavoidable to consider the 2019 gender equity report that documented how Black women in the city experience disproportionately poor outcomes across health and quality of life measures, confirming that access to care is structurally uneven. Beverly’s work offers a way to read those conditions not as isolated failures, but as shared regional systems that shape many aspects of our daily lives, including how long and how well one is allowed to live.

Tara Fay Coleman is an artist, independent curator, writer, and cultural worker from Buffalo, NY. Her practice aims to explore how power, race, and history shape what is seen, and what is systematically obscured. Working across art, writing, and curation, she centers Black cultural production that resists dominant narratives, and reclaims the right to self-representation. Rooted in lived experience, her work aims to challenge institutions to confront their exclusions, while creating space for stories long marginalized. Her goal is to always curate with a commitment to presence, complexity, and care, and she envisions cultural spaces where artists are not only visible, but central, and where art fosters joy, connection, and self-determination. Tara Fay currently lives and works in between Pittsburgh, PA, and New Haven, CT.

Leave a comment