by Grant Catton

Is it time for Keith Haring to take his place among the art gods?

Thirty-four years after his death of AIDS in 1990, Keith Haring has now been gone longer than he was alive. In the past three decades there has been plenty of time for his paintings to circulate to museums in the far corners of the world, museums that wouldn’t touch his art while he was alive. Plenty of time for his art to also grace millions of posters, t-shirts, hats, hand-bags, mugs, and indeed to become so much a part of our culture that it’s practically atomized into the air we breathe. Plenty of time for his peers on the Downtown Manhattan scene of the late 70s and early 80s to get famous, write books, have books and movies made about them, and – in the case of Jean-Michel Basquiat, at least – become deified as Art Gods themselves.

There has also been plenty of time for High Culture and Popular Culture to fuse in a way that was still unthinkable when Haring was alive. Today, because something is popular and commercially successful no longer excludes it from being taken seriously. Great T.V. shows and films are now studied with the same rigor as literature. The New Yorker magazine now reviews Taylor Swift albums and Game of Thrones seasons in its pages right next to reviews of symphonies and ballets. And, I would like to add: Thank God. The idea that art needs to be wrapped in some antiquated, elitist format and be difficult to access is what prevents people from being able to approach it.

But the art world seems to be the last to catch up. Art critics still scoff at the likes of Banksy, KAWS, and Jeff Koons. Because their work is not good? Perhaps. Because it is popular, accessible, and therefore deemed “easy”? Without a doubt. Likewise, everywhere Haring’s artwork is discussed in any kind of critical way, questions about whether he was “too commercial,” and whether he was “a serious artist,” still dominate the conversation.

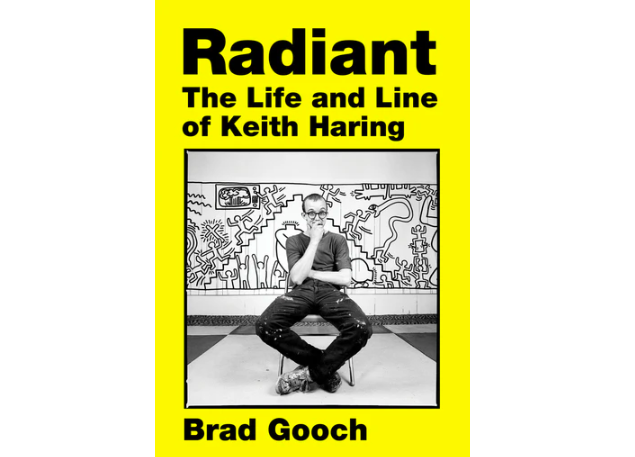

Those questions existed during Haring’s life and will remain. But the time is ripe for a thorough and complete biography of the artist, and by a qualified author at an appropriate historical remove. Enter Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring, written by Brad Gooch and published this year by HarperCollins. It is a book that – in my opinion – will become the definitive text on Haring’s life and work.

The author – who has written biographies of Flannery O’Connor and Frank O’Hara – was ideally positioned to write this biography. Gooch, like the subject of his book, is also a gay man who came of age in 1980s New York during the peak of the AIDS epidemic. Furthermore, Gooch and Haring, while not “friends,” as Gooch is careful to point out in the Acknowledgments, were in the same social circles and knew many of the same people, enabling Gooch to get extensive access to Haring’s family, friends, and others who knew him well for interviews.

As Gooch writes: “…I was sensing that some of the history and context…was being lost. I hoped to reconnect those dots for readers. Haring also had worn his knowledge and ambition too lightly during his lifetime. His was a major contribution still often hidden in plain sight.” In Radiant, Gooch closely details Haring’s influences and his journey to achieving his signature style, attempting to show once and for all that Haring’s art, even if popular and now wildly ubiquitous, had extensive philosophical and artistic underpinnings.

For any Pittsburgher, one of the highlights of the book will be Chapter 3 – appropriately titled “Pittsburgh” – in which Gooch details Haring’s two years spent in the Steel City. Enrolling somewhat reluctantly in the Ivy School of Professional Art, a now-defunct two-year art school located in Perry South, Haring lived in Pittsburgh from fall 1976 intermittently until around August 1978.

According to Gooch, Haring formed key elements of his style by studying works by Pierre Alechinsky and Jean Dubuffet in the Carnegie Museum of Art. Furthermore, he had his first show in the cafeteria of Fisher Scientific, then based in Oakland, where he worked serving food at the time, and soon followed it up with another exhibition at what is now the Pittsburgh Center for Arts and Media (then called the Pittsburgh Center for the Arts), where he also worked.

By now so much has been written about the hallowed Downtown Manhattan scene of the late 70s and early 80s – a time and place that launched so many careers – that it is difficult to add anything to the lore. For me, Gooch’s detailed histories of The Mudd Club and Club 57 – two DIY venues that fused music and art – were fascinating to read but, then again, these clubs now have their own books written about them. Also particularly sentimental to read about were Haring’s early friendships with Basquiat and Kenny Scharf just kicking around the city, flat broke and trying to make as much art as possible, even running with Madonna who was a fixture on that scene as well. That was, of course, long before Haring kept company with the likes of Andy Warhol, Dennis Hopper, and Yoko Ono.

One thing Radiant shed a lot of light on was how much Haring collaborated with street artists, creating hundreds of public art projects with street and graffiti artists of the day and even helping launch the careers of LA2 and others. Indeed, throughout his career Haring seemed determined to involve himself and his art as much as possible in the wider community.

Even when his popularity caused him to become the target of accusations that he was a “sellout” and when his murals were painted over by other artists, he retained his commitment to public art throughout his life, eventually using his art to raise awareness for social causes like AIDS, drug abuse, and apartheid.

No discussion of Haring’s life and work could be complete without mentioning that, in 1986, he opened up a store to sell his own artwork called “The Pop Shop” claiming that, far from being a money grab, it was in fact an attempt to bring his art directly to people and to undermine the sellers of counterfeit Haring goods, which had become rampant. The existence of The Pop Shop seems always to be the key piece of evidence for those who decry Haring and his art as too commercial; however, I think it opens up an interesting debate about artistic integrity vs. commercial viability.

Ultimately, Gooch does not come down too strongly either way, sticking instead to a balanced and eloquently-written presentation of the facts and interviews as impartially as possible. Even with that impartiality, I think it is impossible to come away from reading Radiant without seeing Keith Haring as a generous, gregarious, open-hearted individual as well as a deeply serious artist who just happened to have the mixed fortune of being extremely popular during his lifetime and made the best of it.

Is it Keith Haring’s time to be turned into a god? It is a question worth asking. But it is an academic one. Ultimately, those of us who are interested will read, watch, and otherwise research the lives of the artists whose work means something to us, taking what we can from their stories. Whether or not Haring becomes deified,Radiant will take its place as one of the great contemporary artist biographies and, most importantly, ensure that Haring’s story, properly and thoroughly told, lives on for future generations.

For more information and to purchase Radiant: The Life and Line of Keith Haring, click here: https://www.harpercollins.com/products/radiant-brad-gooch?variant=41070919680034

***

Grant Catton is a Pittsburgh-based visual artist working in acrylics, collage, and mixed media sculpture.