by Emma Riva

To get into Eschaton, I first trespassed in a lot marked “no trespassing.” This is not my first rodeo with post-industrial sites, so I was ready for that to be the entrance—stumbling over graffiti-mottled plywood and cracks in asphalt overrun with goldenrod. Crickets purred the end of summer and the concrete was stained dark with recent rain. Eschaton, which I later discovered had a much easier to access entrance, featured Andrew Allison, Steve Alexis, Jasen Bernthisel, Hibs, Mike Kelly, Julie Lee, Joshua Rievel, and Dyvika Peel. It takes its name from eschatology, the study of the end of the world, and takes place in a quasi-abandoned church on Mulberry Street in Wilkinsburg with no electricity. Yet the show brims with electricity of its own.

Eschaton is a fitting first recap for Petrichor because it genuinely felt like something different in Pittsburgh. Curator and artist Jacquet Kehm was interested in using the Center for Civic Arts space for a large, multimedia group show due to feeling that there were “rungs on the ladder” missing from Pittsburgh’s art scene. “The city has large cultural institutions, a few commercial galleries, but not a lot of large-scale resources for installation or less traditional art outside of the Mattress Factory,” he told me.

Part of what set Eschaton apart was the sheer scale of it. Rather than the four walls of a gallery space, the Center for Civic Arts expands across several rooms of the former worship space. But the physical space element was just one way the show felt like it took on a different energy than other Pittsburgh art events I’ve attended. I got the sense that people from different factions within the art scene were there—DIY musicians from local industrial venues, coworkers of some of the artists at the Pittsburgh Cultural Trust, writers who’d attended graduate programs together.

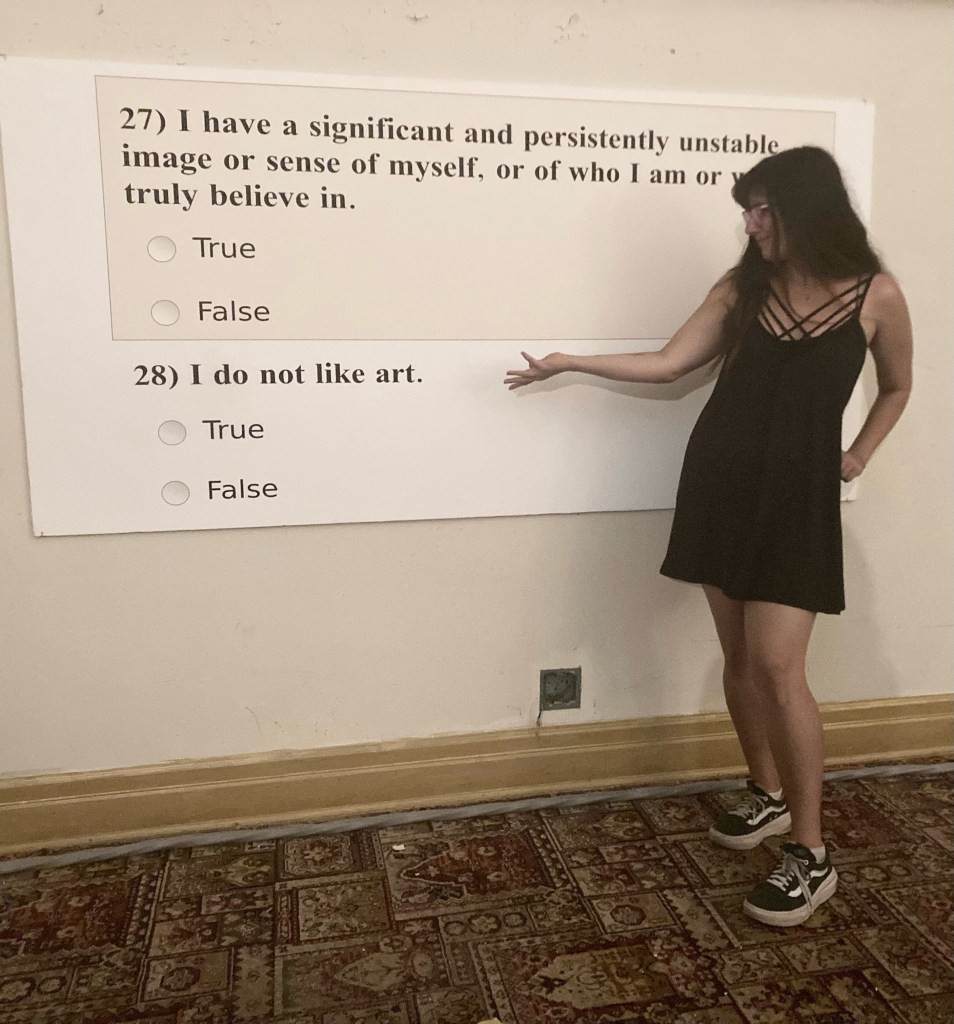

The artists, too, make up a wide range of ages, walks of life, and mediums. Living and dead, installation and sound, color and greyscale, text and installation. Eschaton thinks big and spans wide. In the first room, Dyvika Peel’s The Big Test graces one wall while the metalworking of James Shipman, Steve Alexis, and some of curator Jacquet Kehm’s own work create a forest of iron on the carpeted floor.

One of the organizers at Center for Civic Arts inherited James Shipman’s artwork after his passing, and Kehm found himself affected deeply by the sculptures. He made some of his own work inspired by Shipman. “A lot of the time you only get people to put you’re your work in a retrospective if you make it really big, otherwise when you pass your stuff ends up in a landfill or Goodwill, which is a real shame,” Kehm said. There’s a real sense of angst and sadness in Shipman’s, Kehm’s, and Alexis’s work, especially in this setting.

Objects which might be in a domestic space become distorted. There are layers and layers of metal and wood—bars, poles, and rockers start to feel obstructive. Peel’s The Big Test is a stark literal contrast to a room almost entirely made up of work that offers no words or explanations. The empty text bubbles that don’t convey whether you’re meant to answer true or false. I only recently learned about Peel’s work, and one of her biggest strengths is her frank straightforwardness in her art.

Throughout Eschaton, there’s a mixture of tongue-in-cheek humor and profound sadness, a mixture of nihilism and earnestness. A lot of installation work is like this—Installation gets a bad rep for being the ultimate form of pretension, but it actually can challenge viewers to be less pretentious. It forces us to look at work with fewer layers of judgment, or expose the ways we look at things.

At 6PM during the Eschaton opening, the show transitioned into another art form that gets a bad rep for being opaque and pretentious: performance art. “I included a performance because I wanted a cross-collaboration between different disciplines,” Kehm explained. “You look at collectives like the Surrealists, they didn’t divide or define themselves.” Artist Gunner Lebuff put on a solo performance called “Leviathan,” all original material written for the opening. Lebuff wore a bright green mermaid tell as she sang and recited poetry about the chaos. Jacquet Kim’s sculpture smh / staunchly maniacal harmonies takes on a new meaning in the twilight, cerulean Giant Eagle bags and orange Home Depot bags glimmering in the light through the stained glass as Lebuff’s voice rose.

In that same main room was Mike Kelly’s “Pittsburgh puddle museum,” a corner of the otherwise large and foreboding room surrounded by jars of puddles labeled with tape. Kelly’s installation is an honest-to-God triumph: it’s visual poetry, strange, thought-provoking, and concluding in something beautiful and earnest and real.

You may be getting a longer piece about this installation at some point, because the experience of being inside of it was almost indescribable. It mystified me in the way artwork rarely does. A map of the puddles across the city doesn’t designate which puddle is which, but provides a scope for their sources. I found myself searching for which puddle was closest to my apartment—we all search for familiarity within what we see. Kelly’s handwriting offers small glimpses. this puddle appreciates you. a puddle from Pittsburgh’s past. there are dogs that know more about this puddle than you ever will. shake this puddle until you feel something, anything.

The puddles in jars feel like stand-ins for life’s small intimacies. I felt unable to leave it. Heinz field parking lot. Homewood cemetery. Fifth Ave. I’ll never know where this puddle’s parts came from. I couldn’t believe that I felt like I was about to cry surrounded by jars of puddles. Were they even really from puddles? Kelly could have easily just called them that and filled them with the contents of water bottles. One shelf in the corner featured a jar spilling out pennies, the most useless of currencies but the most shiny and distinctive.

Somehow, my gallery-going companion multimedia artist Aletheia Alev and I got to discussing the nature of love while shaking the puddle titled shake this puddle until you feel something, anything. Apparently, it worked. “Why am I talking about my feelings so much in the puddle room?” she said, looking at me with a mixture of panic and awe. So we knew what we had to do: we hunted down Kelly among the other guests to ask him about the installation.

When we found him, someone had another question: “So, could we drink the puddles?”

“I would drink one right now,” Kelly said. “I’m always looking for ways to get people to cross the street when they see me, so this is a good one…” he said, shrugging as he started gesticulating slurping water out of a puddle.

This off-color joke doesn’t do justice to the depth of Kelly’s work. He started making the puddle jars after seeing a damp puddle in the building itself while working on it. He works as an electrician and provided installation support for Eschaton, and at the same time ended up contributing one of the most moving works I’d seen in a long time. “As I was working, I found myself asking what’s the potential of this building—what is low, how much richness can you find in something that’s avoided and ignored?” In the face of something as big as the apocalypse, what’s left is small.

Eschaton excels in its scope and use of space in a way that far exceeds many other shows. It isn’t without its hiccups, but it thinks big. “Eschatology is a coping mechanism to the highest degree,” Kehm expressed to me. Art, too, is a sort of coping mechanism, and the work within Eschaton explores and exposes that, from Hibs’s macabre but sweet sculpture of a welding mask inside a shroud with a vintage photo in it to the bright colors but eerie emptiness of Andrew Allison’s installation room.

We all do our own personal eschatologies all the time. I’m going to run out of money. Everyone I love will leave me. This stomach cramp is actually colon cancer. No one will ever truly know me. Catastrophizing is the name of the game. But, as the show asks, what does pondering the end provide the living? Maybe there is something universal in pondering destruction, but there’s also something universal in creation. Eschaton was irreverent and fun and out of the ordinary. Walking through it felt a little bit like exploring the setting of a video game with new nooks and crannies everywhere I turned. Yes, its scale is impressive, but what makes it unique are its small subtleties, which is a good lesson for any arts organization. Am I starting a magazine by writing about a show about the end of the world? Maybe. But nothing can start without endings, and nothing can end without a new beginning.

Eschaton is open through November at the Center for Civic Arts, 710 Mulberry Street. And yes, you can touch the puddles in the puddle museum.

Leave a reply to YOU’RE DOING IT WRONG GETS IT RIGHT – PETRICHOR Cancel reply