Roaming: a column | somewhere between observation and critique | art and sound and movement by David Bernabo

Many art openings happen at night. It’s normal. Practical, even. Happens all the time. But in some galleries, you notice it. Maybe not in the brightly lit, sealed off, white-walled spaces. But in other spaces – rawer spaces – evening, with its dim moonlight and passing headlights, becomes a player.

It was evening (6pm) when I arrived at the Platonic Solids exhibition, curated by artist Liz Rudnick, at (___), pronounced “Blank Space.” (___)’s windows aren’t covered. They are open to the neighborhood. They invite the neighborhood in, and in doing so, also invite the night.

The innards of (___) are hardly blank. This was my pre-show hot take that I thought was solid, possibly obvious, but still a good vehicle to discuss the wealth of pre-existing visual information in (___), the challenge that this poses to exhibiting artists, and the nudge for artists to approach their work in a site-specific manner. But I got scooped by Rudnick’s curatorial statement.

“(___) isn’t blank. In fact, what differentiates it from other art spaces is its fullness,” writes Rudnick. (___)’s lack of blankness takes the form of what appears to be an emptied and partially rehab’d second floor of a house. Walls have holes. Doors show signs of multiple coats of paint. Radiators sit heavy on wood floors framed in roughed-up trim.

This means that the selected artists – Andrew W. Allison, Haylee Ebersole, Georgia Hourdas, Arush Kalra, Millie Marshall, Rachel Morgan Simmons – need to bring a certain sensitivity to their installations. A sensitivity to what can be added, covered, enhanced, fooled, forgotten, remembered.

My first reaction to the layout of the show is that there is a hierarchy. Three of the main rooms are grounded by large collaborative works from Andrew W. Allison and Haylee Ebersole. A wide ladder, a roadblock, and the gallery’s (or former house’s) bathtub each take centerstage in a room. These objects are often the highest and lowest things in the room, and certainly the bulkiest. Allison and Ebersole bejewel these structures in paper collage, clay forms, foam, glitter, paint, and Ebersole’s iconic gelatin sculptures. The results feel magical, haphazard, and nostalgic, as if they are reaching back to an earlier part of life where justification or rationale is not a prerequisite for making decisions. Intuition rules.

The prominence of these objects, to my mind, defines the universe in which the other artworks live. Adjacent to A Volcano Buries Itself/Short Sky – Allison and Ebersole’s ladder sculpture – is Georgia Hourdas’ Candy Mushrooms in the Sky, a printed fabric and oil paint piece, that overlays painted mushroom shapes onto a printed image of flowers against a blue sky. The painted images are flat, clean, and vibrant, and it’s quite fun to pick out the order of operations of the painted layers. This painting and the other works by Hourdas that employ the same layering technique contain an internal logic where a balance is struck between recognizable and abstract painted shapes and literal photographic material. These pieces, as a whole, feel like a garden or landscape with a code that needs to be cracked.

In the entry room – the one with the tub – Rachel M. Simmons presents poems laser-etched into black marble. One piece tells of the remorse of ripping earthworms in half while digging up the dirt that rests under the black marble. A trio of poems on a mantle deal to some degree with loss: past lives, hopelessness, obliteration. But there’s more to them than loss. There’s a certain interaction with the unknown. A mystery. But all of this is rendered, punctured into the marble, possibly to ensure that these words endure. Earlier, I mentioned it was nighttime. I mentioned this because the yellow whine of the gallery’s central light takes on greater effect without sunlight. And that yellow light, when cast upon the marble, reminds me of the yellow lights of Allegheny Cemetery just after dusk. It’s an association that might dissolve when viewing this show in the daylight.

The relative cleanness of line and intention of Hourdas’ paintings and Simmons’ marble works contrasts both the busyness of the gallery space and the wildness of Allison and Ebersole’s many varied pieces, which frequently crawl around base boards and find their way into holes in the walls.

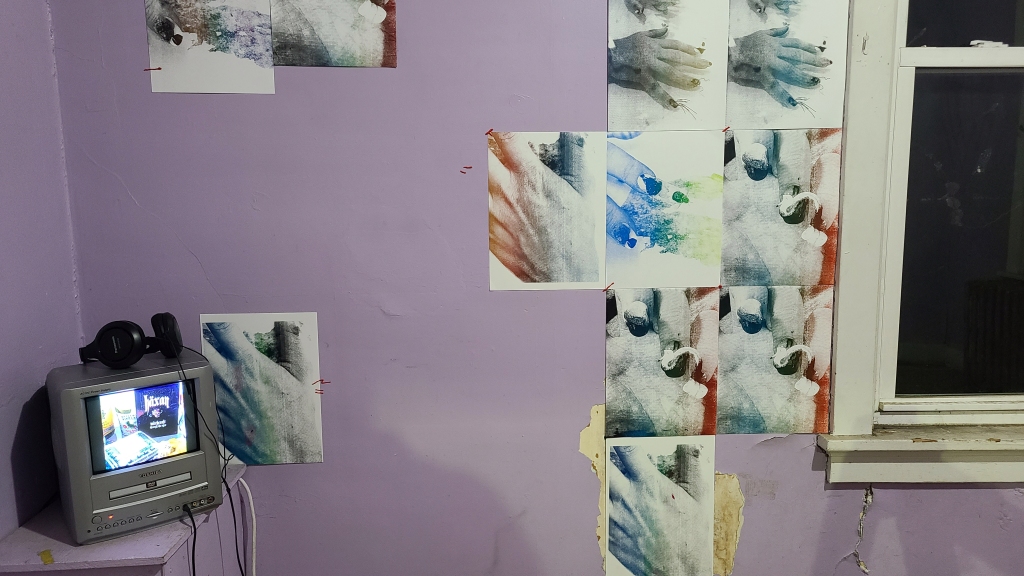

A few favorites. Witch Finger is a 5.5 minute video loop. I didn’t quite catch everything that the video had to offer as a small child started flipping through the 125 channels of static on the Toshiba TV, but there is something nice about seeing what looks like a DVD copy of the 1922 horror essay film, Häxan, sitting next to a jar of pickles and a container of berries. Surrounding the video are a variety of screenprints titled Things That Form More Than Once that portray Allison’s fingernails embellished with small sculptures. The prints create a nice movement in the room, creating a feeling of swirling behind the duo’s larger Block Party Blocker. Testing one’s knees and the ability to bend them, Moonlit Vampyre caught in a trampoline is a sneaky piece. If you don’t look down, you might miss it. Viewed through a cutout in the wall, a sad looking layer cake sits in what might be a supply closet. I loved it!

There are two rooms that I haven’t mentioned yet. Double Sit is a room-sized installation by Simmons. You are invited to sit and listen to a recording of shifting white noise and muffled voice via a landline phone. Barely noticeable wall text – two poems and a quote, with some phrases emphasized with a shaded backing – mirrors the feeling of one of the printed phrases, “we notice their passing shadow as a feeling or a dream.”

Diagonal to Simmons’ room is Sabbatical, a collaborative live audio-visual performance by Arush Kalra and Millie Marshal. Amidst a bevy of video projections depicting line animations, sped up transportation videos, and decorative patterns, the duo craft rhythmic collages from digital and vinyl sources. It’s an information overload for sure, but oddly, because of it’s regular cadence of sound and visuals, it is a nice palette cleanser from the information overload happening in the main gallery rooms.

In 2016, I interviewed Ebersole for The Glassblock. We spoke about her use of dehydrated and crystallized gelatin – a material that originates in connective tissue, bones, ligaments, and ends up as mainly collagen. Speaking of the material, Ebersole said, “It’s a great exercise in letting go of control.” To some extent, “letting go” is a helpful way to view Platonic Solids. You can’t get hung up on the limitations or infinite detail of (___) as a gallery and you don’t need to understand everything happening within the 37 works on display. All you need to do is show up and let this weird, wild show make you weirder.

David Bernabo is an oral historian, musician, artist, and independent filmmaker with a deep interest in local history and its repercussions on today’s Pittsburgh.