by Emma Riva

All images courtesy of Silver Eye Center for Photography

Every moment is a negotiation of intimacy. As I type this out in an airport terminal, a Starbucks employee knows my name, travelers around me see my face, but none of these relationships are truly close, knowing ones. Most people are in a liminal intimacy with each other, between the known and the unknown—and this is also a version of the relationship between the viewer and the work of art. The fourth iteration of Silver Eye Center for Photography’s Radial Survey sees lens artists negotiating these questions of liminal spaces and intimate encounter.

Shows like Radial Survey, which draws form the 300-mile radius around Pittsburgh, excluding New York and Chicago, present an inherent challenge. When the focus is geographic rather than thematic, it can be hard to create a coherent curatorial vision. But Executive Director Leo Hsu and Deputy Director & Director of Programs Helen Trompeteler are a dynamic team and took recommendations from the 2023 artist lineup to craft this version of the biennial. (From the last iteration, I remember most clearly the work of the hugely gifted Detroit artist Akea Brionne, now a Forbes 30 Under 30 recipient!)

Though 2023’s was enjoyable, 2025’s Radial Survey is more cohesive. The lineup of Ian John Solomon, Juan Orrantia, McNair Evans, Christine Lorenz, Amelia Burns, and SHAN Wallace is full of work that pushes the boundaries of photography as a form while still embracing the traditions behind it.

I first found the idea of the liminal and the intimate in Ian John Solomon’s Polaroid series Solar Fields. Art consumers often don’t think of photography as being material, but Solar Fields is a striking use of Polaroid to compose a unique image that’s much more ephemeral than a digital camera photo. The images are quintessential “liminal spaces,” where the familiar feels unfamiliar or the unfamiliar feels intimate.

A particularly haunting one in the Solar Fields series is on the bottom left, a pale ghost of a home eroded into green, the corners of the paper frayed. Based out of Detroit, Solomon’s work plays with the notion of what growth and decay is and asks powerful questions about whether there can be innovation without extraction. Solar Fields alludes to how solar energy developments have displaced historically Black communities, leaving only the homes, without people. In a final image, Solomon shows a hand holding a shell over a former plantation field, evoking powerful emotions about whether histories of violence can ever give way to healing.

On the same wall, Juan Orrantia’s work states it wants to “unsettle histories” of the still life. This is at its most poignant in a hanging inkjet print depicting fish strewn across a seeping tableau of cover. The work made me pause and confide what it means to “unsettle.” The world settler is embedded into it, and it brings to mind how the uncanny or supernatural can be a way to take back power—Blaxploitation films or queer narratives of horror movies.

When I viewed Orrantia’s work through the lens of unsettling not as provocation but as a new way of perceiving, it opened to me. What otherwise looked like abstraction began to become its own visual language. Orrantia is interested in the history of color and how certain colors became associated with racist tropes in still life paintings, and by reclaiming those color compositions, he unsettles and recreates those narratives. He uses the liminal as a home in the work, rather than an unfamiliar place.

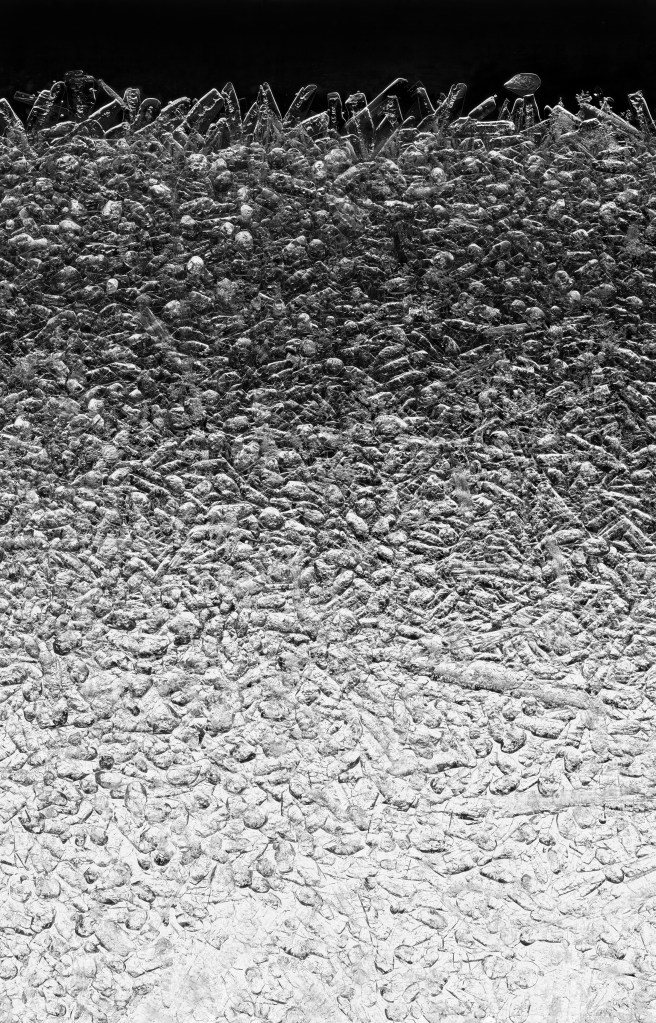

Radial Survey always has one local artist, and Vol. 4 has Christine Lorenz, whose macro photography viewers might recognize from the Pittsburgh Airport. Lorenz’s photography has been compelling to me since I first saw it. Her merging of the arts and science is a refreshing take, and her section of the space uses a technique Silver Eye often employs of putting art outside of the frame and physically on the wall.

There’s an argument to be made that Lorenz’s work actually reaches its fullest expression in that form, expanding beyond a frame or a piece of paper. But this iteration of Lorenz’s photography also features small black desires of salt evaporated into water and let reform. Lorenz has never used the physical salt itself in the work before, and the effect is a glittering gradient. Lorenz’s work has strong ties to Solomon’s in both drawing from histories of extraction. Both bring to mind how often places described as “liminal” or “creepy” are sites of extractions. Old industrial sites and abandoned homes were places of great suffering, and deserve respect beyond sensationalization.

Sometimes I encounter a work of art that feels tailor-made for me, and McNair Evans’ work did that for me. Evans has been riding Amtrak for ten years and invited strangers to write in his journal throughout his travels, documenting with his camera all the way. Hsu described the series as a “cloud of subjectivities.”

The photos Evans took have a gentle sepia tone, and the subjects’ faces have a softness to them. A woman’s bright azure acrylic nail perfectly matches her sweatshirt. Her eyes have a soft gaze behind plastic glasses. This series is a true work of storytelling, combining documentary with a creative vision and a dynamic scale.

It’s one of the most resonant works of photography I’ve seen in a long time. In the surrounding text on the wall, the strangers reveal personal details of their lives to Evans in his journey. Amtrak is quintessential liminal intimacy—passengers are stuck with each other for hours on end, total strangers each on solitary journeys who may never be in the same room again.

Amelia Burns of Detroit takes her own photographs and uses them as collage materials. The series deconstructs memory. There’s something tactile about the fact that Burns collages the work on her phone, rather than using a computer screen. Something about the work feels very Y2K, with echoes of Lisa Frank in it, but that doesn’t mean it’s any less serious. Rather, Burns seems to have captured a sort of millennial kitsch from the earlier eras of digital consumption. The images feel like looking into a diary, and a part of me felt like I was seeing something very private, that only Burns could really understand.

But there are still universal ideas in the images. Trompeteler noted “fear, hope, pleasure, and desire” as some of the themes within the images. The result of the phone collaging is murkier boundaries on each images which result in an effect like the faded wall paint of urban decay. Burns’ work has a humorous bent or kitsch to it, but that doesn’t mean it’s any less serious.

In the Gruber gallery on the far side of Silver Eye, SHAN Wallace works with the idea of surveillance. There’s no auto focus on the 1970s camera she uses, and the result are ghostlike images that harken back to a time when photography was not as true to life. Wallace then runs the images through an analog video mixer, turning them into mesmerizingly incoherent squares of color. Hsu noted the question inherent to Wallace’s work that: “How is light in a formation transformed into something that may or may not be legible?” Like Solomon, she treats photography as material.

Everything in Wallace’s work is analog. Just as Evans did, she photographed transit both inside and outside, the interior and exterior of a Peter Pan bus. It’s work that is highly technical in nature, but also can be encountered without context. Something about the images reminded me of CAPTCHA photos, the images presented to prove a user is human. The photos, despite being considered “lower quality” images are much closer to what the human eye sees.

One of the undercurrents that ties all the photography together is use of past work to create current work. The artists were able to let go of things that were once precious and let them become something new. The past feels both close and far away. The liminal is feeling distant in the familiar. Looking at the photography in Radial Survey, there is a closeness to the artist’s visions, but there is always a divide between the viewer and the artist. For me, the show was at its most effective with Evans, Wallace, and Burns’ work, where the medium of photography morphs into experimental and transformative states, but the work was still legible and evocative.

2025’s Radial Survey walks the line between focus on form and process and focus on concept and social relevance, too. The show is definitely relevant to our current moment, when things feel simultaneously more inter-connected than ever but also full of much deeper divides. This idea is played out by now, but it’s worth it to experience art that you can both feel a sense of comfort from in the same place as art that takes you out of your comfort zone. Art should be both intimate and liminal, and who sees what in which piece will depend on where your position is. In this show, Silver Eye lets viewers approach the work from where they are. If someone knew nothing about the work and nothing about photography, they would still be able to feel the intensity of its emotional undercurrents—something of a rarity in contemporary art that SIlver Eye is to be commended for.

Radial Survey Vol. 4 is on view through February 7.

This month’s articles are produced with support from the Frick Pittsburgh in conjunction with their landmark exhibition The Scandinavian Home: Landscape and Lore. Get cozy as the seasons change with David and Susan Warner’s collection of paintings, tapestries, and sculptures from around the Nordic region, including an early-career Hilma af Klint. Tickets now on sale.

Leave a reply to petrichorpgh Cancel reply